Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

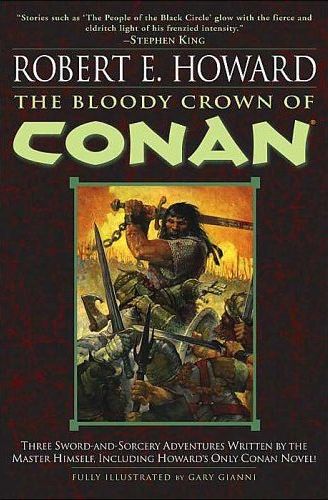

Published in The Bloody Crown of Conan, 2004, as “Untitled Synopsis” and “Untitled Draft”

(the “Drums . . .” title is from the version L. Sprague DeCamp completed and published in Conan the Adventurer 1969).

| Untitled Synopsis | Untitled Draft |

Amalric, a son of a nobleman of the great house of Valerus, of western Aquilonia, halted at a palm-bordered spring in the desolate vastness of the desert that lies south of Stygia, with two companions, members of the bandit tribe of Ghanata, a negro race mixed with Shemitish blood. The Ghanatas with Amalric were named Gobir, and Saidu. Just at dusk, as they prepared to eat their frugal meal of dried dates, the third member of the tribe rode up—Tilutan, a black giant, famous for his ferocity and swordsmanship. He carried across his saddle-bow an unconscious white girl, whom he had found falling with exhaustion and thirst out on the desert as he hunted for the rare desert antelope. He cast the girl down beside the spring and began reviving her. Gobir and Saidu watched Amalric, expecting him to try to rescue her, but he feigned inidifference, and asked them which would take the girl after Tilutan wearied of her. That started an argument, and he cast down a pair of dice, telling them to gamble for her. As they crouched over the dice, he drew his sword and split Gobir’s skull. Instantly Saidu attacked him, and Tilutan threw down the girl and ran at him, drawing his terrible scimitar. Amalric wheeled about, causing Saidu to receive the thrust instead of himself, and hurling the wounded man into Tilutan’s arms, grappled with the giant. Tilutan bore Amalric to the earth, and was strangling him, and threw him down, and rose to procure his sword and cut off his head. But as he ran at him, his girdle became unwound and he tripped and fell over it. His sword flew from his hand and Amalric caught it up and slashed his head nearly off. Then he reeled and fell senseless. He came to life again with the girl splashing him with water. He found she spoke a language akin to the Kothic, and they could understand each other. She said her name was Lissa; she was a beautiful youngster, white soft white skin, violet eyes, and dark wavy hair. Her innocence shamed the wild young soldier of fortune, and he forwent his intention of raping her. She supposed that he had fought his companions merely to rescue her, and he did not disillusion her. She said that she was an inhabitant of the city of Gazal, lying not far to the southeast. She had run away from Gazal, on foot, her water supply had given out, and she had fainted just as she was discovered by Tilutan. Amalric put her on a camel, he mounted a horse—the other beasts having broken away and bolted into the desert during the fight—and dawn found them approaching Gazal. Amalric was astounded to find the city a mass of ruins, except for a tower in the southeastern corner. When he spoke of it, Lissa turned pale, and begged him not to talk of it. He found the people were a dreamy, kindly race, without practical sense, much given to poetry and day dreams. There were not many of them, and they were a dying race. They had come into the desert and built the city over an oasis long ago—a cultured, scholarly race, not given to war. They were never attacked by any of the fierce and brutal nomadic tribes, because these people looked on Gazal with superstitious awe, and worshipped the thing that lurked in the southeastern tower. Amalric told Lissa his story—that he had been a soldier in the army of Argos, under the Zingaran Prince Zapayo da Kova, which had sailed in ships down the Kushite coast, landed in southern Stygia, and sought to invade the kingdom from that direction, while the armies of Koth invaded from the north. But Koth had treacherously made peace with Stygia, and the army in the south was trapped. They found their escape to the sea cut off, and tried to fight their way eastward, hoping to gain the lands of the Shemites. But the army was annihilated in the desert. Amalric had fled with his companion, Conan, a giant Cimmerian, but they had been attacked by a band of wild-riding brown-skinned men of strange dress and appearance, and Conan was cut down. Amalric escaped under cover of night, and wandered in the desert, suffering from hunger and thirst, until he fell in with the three vultures of the Ghanata. He spoke of the unreality of the city of Gazal, and Lissa told him of her childish yet passionate desire to break way from the stagnating environment, and see something of the world. She gave herself to him as naturally as a child, and as they lay together on a silk-covered couch in a chamber lighted only by the starlight, they heard awful cries from a building nearby. Amalric would have investigated, but Lissa clung to him, trembling, and told him the secret of the lonely tower. There dwelt a supernatural monster, which occasionally descended into the city and devoured one of the inhabitants. What the thing was, Lissa did not know. But she told of bats flying from the tower at dusk, and returning before dawn, and of piteous cries from victims carried up into the mysterious tower. Amalric was unnerved, and recognized the thing as a mysterious deity worshipped by certain cults among the negro tribes. He urged Lissa to flee with him before dawn—the inhabitants of Gazal had so far lost their initiative that they were helpless, unable to fight or flee—like men hypnotized, which the young Aquilonian believed to be the case. He went to prepare their mounts, and returning, heard Lissa give an awful scream. He rushed into the chamber and found it empty. Sure she had been seized by the monster, he rushed to the tower, ascended a stair, and found himself in an upper chamber in which he found a white man, of strange beauty. Remembering an ancient incantation repeated to him by an old Kushite priest of a rival cult, he repeated it, binding the demon into his human form. A terrific battle then ensued, in which he drove his sword through the being’s heart. As it died it screamed horribly for vengeance and was answered by voices from the air. Then it altered in a hideous manner, and Amalric fled in horror. He met Lissa at the foot of the stair. She had been frightened by a glimpse of the creature dragging its human prey through the corridors, and had run away in ungovernable panic and hidden herself. Realizing that her lover had gone to the tower to seek her, she had come to share his fate. He crushed her briefly in his arms, and led her to where he had left their mounts. It was dawn when they rode out of the city, she upon the camel and he upon the horse. Looking back on the sleeping city, in which there were no animals at all, they saw seven horsemen ride out—black robed men on gaunt black horses—following them. Panic assailed them, for they knew those were no human riders. All day they pushed their steeds mercilessly, westward, toward the distant coast. They found no water, and the horse became exhausted just before sundown. All the while the black figures had followed relentlessly, and as dusk fell they began to close in rapidly. Amalric knew they were ghoulish creatures summoned from the abyss by the death cry of the monster in the tower. As darkness gathered, the pursuers were close upon them. A bat-shaped shadow blotted out the moon, and the fugitives could smell the charnel-house reek of their hunters. Suddenly the camel stumbled and fell, and the fiends closed in. Lissa shrieked. Then there came a drum of hoofs, a gusty voice roared, and the fiends were swept away by the headlong charge of a band of horsemen. The leader of these dismounted and bent over the exhausted youth and girl, and as the moon came out, he swore in a familiar voice. It was Conan the Cimmerian. Camp was made and the fugitives given food and drink. The Cimmerian’s companions were the wild-looking brown men who had attacked him and Amalric. They were the riders of Tombalku, that semi-mythical desert city whose kings had subjugated the tribes of the southwestern desert and the negro races of the steppes. Conan told them that he had been knocked senseless and carried to the distant city to be exhibited to the kings of Tombalku. There were always two of these kings, though one was generally merely a figure-head. Carried before the kings, he was doomed to die by torture, and he demanded that liquor be given him, and cursed the kings roundly. At that, one of them woke from his drowse with interest. He was a big fat negro, while the other was a lean brown-skinned man, named Zehbeh. The negro stared at Conan, and greeted him by the name of Amra, the Lion. The black man’s name was Sakumbe, and he was an adventurer from the West Coast who had been connected with Conan when the latter was a corsair devastating the coast. He had become one of the kings of Tombalku partly because of the support of the negro population, partly because of the machinations of a fanatical priest, Askia, who had risen to power over Zehbeh’s priest, Daura. He had Conan instantly freed, and raised to the high position of general of all the horsemen—incidentally having the present incumbent, one Kordofo, poisoned. In Tombalku were various factions—Zehbeh and the brown priests, Kordofo’s kin who hated both Zehbeh and Sakumbe, and Sakumbe and his supporters, of whom the most powerful was Conan himself. All this Conan told Amalric, and the next day they rode on toward Tombalku. Conan had been riding to drive from the land the Ghanata thieves. In three days they reached Tombalku, a strange fantastic city set in the sands of the desert, beside an oasis of many springs. It was a city of many tongues. The dominant caste, the founders of the city, were a warlike brown race, descendents of the Aphaki, a Shemitish tribe which pushed into the desert several hundred years before, and mixed with the negro races. The subject tribes included the Tibu, a desert race, of mixed negro and Stygian blood; and the Bagirmi, Mandingo, Dongola, Bornu, and other negro tribes of the grasslands to the south. They arrived in Tombalku in time to witness the horrible execution of Daura, the Aphaki priest, by Askia. The Aphaki were enraged, but helpless against the determined stand of their black subjects to whom they had taught the arts of war. Sakumbe, once a man of remarkable courage, vitality and statescraft, had degenerated into a mountainous mass of fat, caring for nothing except women and wine. Conan played dice with him, got drunk with him, and suggested that they eliminate Zehbeh entirely. The Cimmerian wished to be a king of Tombalku himself. So Askia was persuaded to denounced Zehbeh, and in the bloody civil war that followed, the Aphaki were defeated, and Zehbeh fled the city with his riders. Conan took his seat beside Sakumbe, but strive as he would, he found the negro the real ruler of the city, because of his ascendency over the black races. Meanwhile, Askia had been suspicious of Amalric, and he finally denounced him as the slayer of the god worshipped by the cult of which he was a priest, and demanded that he and the girl be given to the torture. Conan refused, and Sakumbe, completely dominated by the Cimmerian, backed him up. Then Askia turned on Sakumbe and destroyed him by means of an awful magic. Conan, realizing that with Sakumbe slain, the blacks would rend him and his friends, shouted to Amalric, and cut a way through the bewildered warriors. As the companions strove to reach the outer walls, Zehbeh and his Aphaki attacked the city, and in a wild holocaust of blood and flame, Tombalku was almost destroyed, and Conan, Amalric and Lissa escaped.

Three men squatted beside the water hole, beneath the sunset sky that painted the desert umber and red. One was white, and his name was Amalric; the other two were Ghanatas, their tatters scarcely concealing their wiry black frames. Men called them Gobir and Saidu; they looked like vultures as they crouched beside the water hole.

Near by a camel ground its cud noisely, and a pair of weary horses vainly nuzzled the bare sand. The men munched dried dates cheerlessly, the black men intent only on the working of their jaws, the white man occasionally glancing at the dull red sky, or out across the level monotony where the shadows were gathering and deepening. He was first to see the horseman who rode up and drew rein with a jerk that set the steed rearing.

The rider was a giant whose skin, blacker than that of the other two, as well as his thick lips and flaring nostrils, told of negro blood in vastly predominating abundance. His wide silk pantaloons, gathered in about his bare ankles, were supported by a broad girdle wrapped repeatedly about his huge belly; that girdle also supported a flaring-tipped scimitar few men could wield with one hand. With that scimitar the man was famed where ever the dark-skinned sons of the desert rode. He was Tilutan, the pride of the Ghanata.

Across his saddle bow a limp shape lay, or rather hung. Breath hissed through the teeth of the Ghanatas as they caught the gleam of white limbs. It was a white girl who hung across Tilutan’s saddle bow, face down, her loose hair flowing over his stirrup in a rippling black wave. The black grinned with a glint of white teeth, and cast her casually in to the sand, where she lay laxly, unconscious. Instinctively Gobir and Saidu turned toward Amalric, and Tilutan watched him from his saddle. Three black men against one white. The entrance of a white woman into the scene wrought a subtle change in the atmosphere.

Amalric was the only one who was apparently oblivious to the tenseness. He raked back his rebellious yellow locks absently, and glanced indifferently at the girl’s limp figure. If there was a momentary gleam in his grey eyes, the others did not catch it.

Tilutan swung down from his saddle, contemptuously tossing the rein to Amalric.

“Tend my horse,” he said. “By Jhil, I did not find a desert antelope, but I found this little filly. She was reeling through the sands, and she fell just as I approached. I think she fainted from weariness and thirst. Get away from there, you jackals, and let me give her a drink.”

The big black stretched her out beside the water hole, and began laving her face and wrists, and trickling a few drops between her parched lips. She moaned presently and stirred vaguely. Gobir and Saidu crouched with their hands on their knees, staring at her over Tilutan’s burly shoulder. Amalric stood a little apart from them, his interest seeming only casual.

“She is coming to,” announced Gobir.

Saidu said nothing, but he licked his thick lips involuntarily, animal-like.

Amalric’s gaze travelled impersonally over the prostrate form, from the torn sandals to the loose crown of glossy black hair. Her only garment was a silk kirtle, girdled at the waist. It left her arms, neck and part of her bosom bare, and the skirt ended several inches above her knees. On the parts revealed rested the gaze of the Ghanatas with devouring intensity, taking in the soft contours, childish in their white tenderness, yet rounded with budding womanhood.

Amalric shrugged his shoulders.

“After Tilutan, who?” he asked carelessly.

A pair of lean heads turned toward him, blood-shot eyes rolled at the question, then the black men turned and mutually stared at one another. Sudden rivalry crackled electrically between them.

“Don’t fight,” urged Amalric. “Cast the dice.” His hand came from under his worn tunic, and he threw down a pair of dice before them. A claw like hand seized them.

“Aye!” agreed Gobir. “We cast—after Tilutan, the winner!”

Amalric cast a glance toward the giant black, who still bent above his captive, bringing life back into her exhausted body. As he looked, her long lashed lids parted; deep violet eyes stared up into the leering face of the black man, bewilderedly. An explosive exclamation of gratification escaped the thick lips of Tilutan. Wrenching a flask from his girdle, he put it to her mouth. She drank the wine mechanically. Amalric avoided her wandering gaze; one white men and three blacks—either of them his match.

Gobir and Saidu bent above the dice; Saidu cupped them in his palm, breathed on them for luck, shook and threw. Two vulture-like heads bent over the spinning cubes in the dim light. And Amalric drew and struck with the same motion. The edge sliced through a thick neck, severing the wind-pipe, and Gobir fell across the dice, spurting blood, his head hanging by a shred.

Simultaneously Saidu, with the desperate quickness of a desert man, shot to his feet and hacked ferociously at the slayer’s head. Amalric barely had time to catch the stroke on his lifted sword. The whistling scimitar beat the straight blade down on the white man’s head, staggering him. Amalric released his sword and threw both arms about Saidu, dragging him into close quarters where his scimitar was useless. Under the desert man’s rags, the wiry frame was like steel cords.

Tilutan, comprehending the matter instantly, had cast the girl down and risen with a roar. He rushed toward the strugglers like a charging bull his great scimitar flaming in his hand. Amalric saw him coming, and his flesh turned cold. Saidu was jerking and wrenching, handicapped by the scimitar he was still seeking futilely to turn against his antagonist. Their feet twisted and stamped in the sand, their bodies ground against one another. Amalric smashed his sandal heel down on the Ghanata’s bare instep, feeling bones give way. Saidu howled and plunged convulsively, and Amalric, aiding his leap with a desperate heave of his own. They lurched drunkenly about, just as Tilutan struck with a rolling drive of his broad shoulders. Amalric felt the steel rasp under part of his arm, and chug deep into Saidu’s body. The Ghanata gave an agonized scream, and his convulsive start tore himself free of Amalric’s grasp. Tilutan roared a furious oath and wrenching his steel free, hurled the dying man aside, but before he could strike again, Amalric, his skin crawling with the fear of that great curved blade, had grappled with him.

Despair swept over him as he felt the strength of the negro. Tilutan was wiser than Saidu. He dropped the scimitar and with a bellow, caught Amalric’s throat with both hands. The great black fingers locked like iron, and Amalric, striving vainly to break their grip, was borne down, with the Ghanata’s great weight pinning him to the earth. The smaller man was shaken like a rat in the jaws of a dog. His head was smashed savagely against the sandy earth. As in a red mist he saw the furious face of the negro, the thick lips writhed back in a bestial grin of hate, the teeth glistening. A bestial snarling slavered from the thick black throat.

“You want her, you white dog!” the Ghanata mouthed, insane with rage and lust.” Arrrrghhh! I break your back! I tear it out your throat! I—my scimitar! I cut off your head and make her kiss it!”

A final ferocious smash of Amalric’s head against the hard packed sand, and Tilutan half lifted him and hurled him down in an excess of bestial passion. Rising, the black ran, stooping like an ape, and caught up his scimitar where it lay like a broad crescent of steel in the sand. Yelling in ferocious exultation, he turned and charged back, brandishing the blade on high. Amalric rose slowly to meet him, dazed, shaken, sick from the manhandling he had received.

Tilutan’s girdle had become unwound in the fight, and now the end dangled about his feet. He tripped, stumbled, fell headlong, throwing out his arms to save himself. The scimitar flew from his hand.

Amalric, galvanized, caught up the scimitar, and took a reeling step forward. The desert swam darkly to his gaze. In the dusk before him he saw Tilutan’s face suddenly ashy. The wide mouth gaped, the whites of the eyeballs rolled up. The black froze on one knee and a hand, as if incapable of further motion. Then the scimitar fell, cleaving the round shaven head to the chin, where its downward course was checked with a sickening jerk. Amalric had a dim impression of a black face, divided by a widening red line, fading in the thickening shadows, then darkness caught him with a rush.

Something soft and cool was touching Amalric’s face with gentle persistence. He groped blindly and his hand closed on something warm, firm and resilient. Then his sight cleared and he looked into a soft oval face, framed in lustrous black hair. As in a trance he gazed unspeaking, hungrily dwelling on each detail of the full red lips, dark violet eyes, and alabaster throat. With a start he realized the vision was speaking in a soft musical voice. The words were strange, yet possessed an illusive familiarity. A small white hand, holding a dripping bunch of silk was passed gently over his throbbing head and his face. He sat up dizzily.

It was night, under the star-splashed skies. The camel still munched its cud, a horse whinnied restlessly. Not far away lay a hulking black figure with its cleft head in a horrible puddle of blood and brains. Amalric looked up at the girl who knelt beside him, talking in her gentle unknown tongue. As the mists cleared from his brain, he began to understand her. Harking back into half forgotten tongues he had learned and spoken in the past, he remembered a language used by a scholarly class in a southern province of Koth.

“Who are you, girl?” he demanded, prisoning a small hand in his own hardened fingers.

“I am Lissa.” The name was spoken with almost the suggestion of a lisp. It was like the rippling of a slender stream. “I am glad you are conscious. I feared you were not alive.”

“A little more and I wouldn’t have been,” he muttered, glancing at the grisly sprawl that had been Tilutan. She paled, and refused to follow his gaze. Her hand trembled, and in their nearness, Amalric thought he could feel the quick throb of her heart.

“It was horrible,” she faltered. “Like an awful dream. Anger—and blows—and blood—”

“It might have been worse,” he growled.

She seemed sensitive to every changing inflection of voice or mood. Her free hand stole timidly to his arm.

“I did not mean to offend you. It was very brave for you to risk your life for a stranger. You are noble as the knights about which I have read.”

He cast a quick glance at her. Her wide clear eyes met his, reflecting only the thought she had spoken. He started to speak, then changed his mind and said another thing.

“What are you doing in the desert?”

“I came from Gazal,” she answered. “I—I was running away. I could not stand it any longer. But it was hot and lonely and weary, and I saw only sand, sand—and the blazing blue sky. The sands burned my feet, and my sandals were worn out quickly. I was so thirsty, my canteen was soon empty. And then I wished to return to Gazal, but one direction looked like another. I did not know which way to go. I was terribly afraid, and started running in the direction in which I thought Gazal to be. I do not remember much after that; I ran until I could run no further, and I must have lain in the burning sand for awhile. I remember rising and staggering on, and toward the last, I thought I heard some one shouting, and saw a black man on a black horse riding toward me, and then I knew no more, until I awoke and found myself lying with my head in that man’s lap, while he gave me wine to drink. Then there was shouting and fighting –” she shuddered. “When it was all over, I crept to where you lay like a dead man, and I tried to bring you to—”

“Why?” he demanded.

She seemed at a loss. “Why,” she floundered, “why, you were hurt—and—why, it is what anyone would do. Besides, I realized that you were fighting to protect me from these black men. The people of Gazal have always said that the black people were wicked, and would harm the helpless.”

“That’s no exclusive characteristic of the blacks,” muttered Amalric. “Where is this Gazal?”

“It can not be far,” she answered. “I walked a whole day—and then I do not know how far the black man carried me, after he found me. But he must have discovered me about sunset, so he could not have come far.”

“In what direction?” he demanded.

“I do not know. I travelled eastward when I left the city.”

“City?” he muttered. “A day’s travel from this spot? I had thought there was only desert for a thousand miles.”

“Gazal is in the desert,” she answered. “It is built amidst the palms of an oasis.”

Putting her aside, he got to his feet, swearing softly as he fingered his throat, the skin of which was bruised and lacerated. He examined the three blacks in turn, finding no life in either. Then one by one he dragged them a short distance out into the desert. Somewhere the jackals began yelping. Returning to the water hole, where the girl squatted patiently, he cursed to find only the black stallion of Tilutan with the camel. The other horses had broken their tithers and bolted during the fight.

Amalric went to the girl and proffered her a handful of dried dates. She nibbled at them eagerly, while the other sat and watched her, his chin on his fists, an increasing impatience throbbing in his veins.

“Why did you run away?” he asked abruptly. “Are you a slave?”

“We have no slaves in Gazal,” she answered. “Oh, I was weary—so weary of the eternal monotony. I wished to see something of the outer world. Tell me, from what land do you come?”

“I was born in the western hills of Aquilonia,” he answered.

She clapped her hands like a delighted child.

“I know where it is! I have seen it on the maps. It is the westernmost country of the Hyborians, and its king is Epeus the Sword-wielder!”

Amalric experienced a distinct shock. His head jerked up and he stared at his fair companion.

“Epeus? Why, Epeus has been dead for nine hundred years. The king’s name is Vilerus.”

“Oh, of course,” she said, rather embarrassedly. “I am foolish. Of course, Epeus was king nine centuries ago, as you say. But tell me—tell me all about the world!”

“Why, that’s a big order,” he answered nonplussed. “You have not traveled?”

“This is the first time I have ever been out of sight of the walls of Gazal,” she declared.

His gaze was fixed on the curve of her white bosom. He was not interested in her adventures at the moment, and Gazal might have been Hell for all he cared.

He started to speak, then changing his mind caught her roughly in his arms, his muscles tensed for the struggle he expected. But he encountered no restistance. Her soft yielding body lay across his knees, and she looked up at him somewhat in surprize, but without fear or embarrassment. She might have been a child, submitting to a new kind of play. Something about her direct gaze confused him. If she had screamed, wept, fought, or smiled knowingly, he would have known how to deal with her.

“Who in Mitra’s name are you, girl?” he asked roughly. “You are neither touched with the sun, nor playing a game with me. Your speech shows you to be no ignorant country lass, innocent in ignorance. Yet you seem to know nothing of the world and its ways.”

“I am a daughter of Gazal,” she answered helplessly. “If you saw Gazal perhaps you would understand.”

He lifted her and set down in the sand. Rising, he brought a saddle blanket and spread it out for her.

“Sleep, Lissa,” he said, his voice harsh with conflicting emotions. “Tomorrow I mean to see Gazal.”

At dawn they started westward. Amalric had placed Lissa on the camel, showing her how to maintain her balance. She clung to the seat with both hands, showing no knowledge whatever of camels, which again surprized the young Aquilonian. A girl raised in the desert, she had never before been on a camel, nor, until the preceding night, had she ever ridden or been carried on a horse. Amalric had manufactured a sort of cloak for her, and she wore it without question, not asking whence it came, accepting it as she accepted all things he did for her, gratefully, but blindly, without asking the reason. Amalric did not tell her that the silk that shielded her from the sun had once covered the black hide of her abductor.

As they rode she again begged him to tell her something of the world, like a child asking for a story.

“I know Aquilonia is far from this desert,” she said. “Stygia lies between, and the Lands of Shem, and other countries. How is it that you are here, so far from your home land?”

He rode for a space in silence, his hand on the camel’s guide-rope.

“Argos and Stygia were at war,” he said abruptly. “Koth became embroiled. The Kothians urged a simultaneous invasion of Stygia. Argos raised an army of mercenaries, which went into ships and sailed southward along the coast. At the same time, a Kothic army was to invade Stygia by land. I was one of that mercenary army. We met the Stygian fleet and defeated it, driving it back into Khemi. We should have landed and looted the city, and advanced along the course of the Styx—but our admiral was cautious. Our leader was Prince Zapayo da Kova, a Zingaran. We cruised southward until we reached the jungle-clad coasts of Kush. There we landed, and the ships anchored, while the army pushed eastward, along the Stygian border, burning and pillaging as we went. It was our intention to turn northward at a certain point and strike into the heart of Stygia, to form a juncture with the Kothic host which was supposed to be pushing down from the north. Then word came that we were betrayed. Koth had concluded a separate peace with the Stygians. A Stygian army was pushing southward to intercept us, while another already had cut us off from the coast.

“Prince Zapayo, in desperation, conceived the mad idea of marching eastward, hoping to skirt the Stygian border and eventually reach the eastern Lands of Shem. But the army from the north overtook us. We turned and fought. All day we fought, and drove them back in route to their camp. But the next day the pursuing army came up from the west, and crushed between the hosts, our army ceased to be. We were broken, annihilated, destroyed. There were few left to flee. But when night fell, I broke away with my companion, a Cimmerian named Conan, a brute of a man, with the strength of a bull.

“We rode southward into the desert, because there was no other direction in which we might go. Conan had been in this part of the world before, and he believed we had a chance to survive. Far to the south we found an oasis, but Stygian riders harried us, and we fled again, from oasis to oasis, fleeing, starving, thirsting, until we found ourselves in a barren unknown land of blazing sand and empty sand. We rode until our horses were reeling, and we were half delirious. Then one night we saw fires, and rode up to them, taking a desperate chance that we might make friends with them. As soon as we came within range, a shower of arrows greeted us. Conan’s horse was hit, and reared, throwing its rider. His neck must have broken like a twig, for he never moved. I got away in the darkness, somehow, though my horse died under me. I had only a glance of the attackers—tall, lean, brown men, wearing strange barbaric garments.

“I wandered on foot through the desert, and fell in with those three vultures you saw yesterday. They were jackals—Ghanatas, members of a robber tribe, of mixed blood, negro and Mitra knows what else. The only reason they didn’t murder me was because I had nothing they wished. For a month I have been wandering and thieving with them, because there was nothing else I could do.”

“I do not know it was like that,” she murmured faintly. “They said there were wars and cruelty out in the world, but it seemed like a dream and far away. But hearing you speak of treachery and battle seems almost like seeing it.”

“Do no enemies ever come against Gazal?” he demanded.

She shook her head. “Men ride wide of Gazal. Sometimes I have seen black dots moving in lines along the horizons, and the old men said it was armies moving to war, but they never come near Gazal.”

Amalric felt a dim stirring of uneasiness. This desert, seemingly empty of life, never the less contained some of the fiercest tribes on earth—the Ghanatas, who ranged far to the east; the masked Tibu, whom he believed dwelt further to the south; and somewhere off to the southwest lay the semi-mythical empire of Tombalku, ruled by a wild and barbaric race. It was strange that a city in the midst of this savage land should be left so completely alone that one of its inhabitants did not even know the meaning of war.

When he turned his gaze elsewhere, strange thoughts assailed him. Was the girl touched by the sun? Was she a demon in womanly form come out of the desert to lure him to some cryptic doom? A glance at her clinging childishly to the high peak of the camel saddle was sufficient to dispel these broodings. Then again doubt assailed him. Was he bewitched? Had she cast a spell on him?

Westward they forged steadily, halting only to nibble dates and drink water at midday. Amalric fashioned a frail shelter out of his sword and sheath and the saddle blankets, to shield her from the burning sun. Weary and stiff from the tossing, bucking gait of the camel, she had to be lifted down in his arms. As he felt again the voluptuous sweetness of her soft body, he felt a hot throb of passion sear through him, and he stood momentarily motionless, intoxicated with the nearness of her, before he laid her down in the shade of the make-shift tent.

He felt a touch of almost anger at the clear gaze with which she met his, at the docility with which she yielded her young body to his hands. It was as if she was unaware of things which might harm her; her innocent trust shamed him and pent a helpless wrath within him.

As they ate, he did not taste the dates he munched; his eyes burned on her, avidly drinking in every detail of her lithe young figure. She seemed as unaware of his intentness as a child. When he lifted her to place her again on her camel, and her arms went instinctively about his neck, he shuddered. But he lifted her up on her mount, and they took up the journey once more.

It was just before sundown when Lissa pointed and cried out: “Look! The towers of Gazal!”

On the desert rim he saw them—spires and minarets, rising in a jade-green cluster against the blue sky. But for the girl, he would have thought it the phantom city of a mirage. He glanced at Lissa curiously; she showed no signs of eager joy at her home coming. She sighed, and her slim shoulders seemed to droop.

As they approached the details swam more plainly into view. Sheer from the desert sands rose the wall which enclosed the towers. And Amalric saw that the wall was crumbling in many places. The towers, too, he saw, were much in disrepair. Roofs sagged, broken battlements gaped, spires leaned drunkenly. Panic assailed him; was it a city of the dead to which he rode, guided by a vampire? A quick glance at the girl reassured him. No demon could lurk in that divinely molded exterior. She glanced at him with a strange wistful questioning in her deep eyes, turned irresolutely toward the desert, then, with a deep sigh, set her face toward the city, as if gripped by a subtle and fatalistic despair.

Now through the gaps of the jade green wall, Amalric saw figures moving within the city. No one hailed them as they rode through a broad breach in the wall, and came out into a broad street. Close at hand, limned in the sinking sun, the decay was more apparent. Grass grew rank in the streets, pushing through shattered paving; grass grew rank in the small plazas. Streets and courts likewise were littered with rubbish of masonry and fallen stones.

Domes rose, cracked and discolored. Portals gaped, vacant of doors. Every where ruin had laid his hand. Then Amalric saw one spire untouched; a shining red cylindrical tower which rose in the extreme south eastern corner of the city. It shone among the ruins.

Amalric indicated it.

“Why is that tower less in ruins than the others?” he asked. Lissa turned pale; she trembled, and caught his hand convulsively.

“Do not speak of it!” she whispered. “Do not look toward it—do not even think of it!”

Amalric scowled; the nameless implication of her words somehow changed the aspect of the mysterious tower. Now it seemed like a serpent’s head rearing among ruin and desolation. The young Aquilonian looked warily about him. After all, he had no assurance that the people of Gazal would receive him in a friendly manner. He saw people moving leisurely about the streets. They halted and stared at him, and for some reason his flesh crawled. They were men and women with kindly features, and their looks were mild. But their interest seemed so slight—so vague and impersonal. They made no movement to approach him or to speak to him. It might have been the most common thing in the world for an armed horseman to ride into their city from the desert; yet Amalric knew that was not the case, and the casual manner with which the people of Gazal received him, caused a faint uneasiness in his bosom.

Lissa spoke to them, indicating Amalric, whose hand she lifted like an affectionate child. “This is Amalric of Aquilonia, who rescued me from the black people and has brought me home.”

A polite murmur of welcome rose from the people, and several of them approached to extend their hands. Amalric thought he had never seen such vague, kindly faces; their eyes were soft and mild, without fear and without wonder. Yet they were not the eyes of stupid oxen; rather, they were the eyes of people wrapped in dreams.

Their stare gave him a feeling of unreality; he hardly knew what was said to him. His mind was occupied by the strangeness of it all; these quiet dreamy people, in their silken tunics and soft sandals, moving with aimless vagueness among the discolored ruins. A lotus paradise of illusion? Somehow the thought of that sinister red tower struck a discordant note.

One of the men, his face smooth and unlined, but his hair silver, was saying: “Aquilonia? There was an invasion—we heard—King Bragorus of Nemedia—how went the war?”

“He was driven back,” answered Amalric briefly, resisting a shudder. Nine hundred years had passed since Bragorus led his spearmen across the marches of Aquilonia.

His questioner did not press him further; the people drifted away, and Lissa tugged at his hand. He turned, feasted his eyes upon her; in a realm of illusion and dream, her soft firm body anchored his wandering conjectures. She was no dream; she was real; her body was sweet and tangible as cream and honey.

“Come, let us go to rest and eat.”

“What of the people?” he demurred. “Will you not tell them of your experiences?”

“They would not heed, except for a few minutes,” she answered. “They would listen a little, and then drift away. They hardly know I have been gone. Come!”

Amalric led the horse and camel into an enclosed court where the grass grew high, and water seeped from a broken fountain into a marble trough. There he tethered them, then he followed Lissa. Taking his hand she led him across the court, into an arched doorway. Night had fallen. In the open space above the court, the stars were clustering, etching the jagged pinnacles. Through a series of dark chambers Lissa went, moving with the sureness of long practise. Amalric groped after her, guided by her little hand in his. He found it no pleasant adventure. The scent of dust and decay hung in the thick darkness. Under his feet sometimes were broken tiles, by the feel of them, sometimes worn carpets. His free hand touched the fretted arches of doorways. Then the stars gleamed through a broken roof, showing him a dim winding hallway, hung with rotting tapestries. They rustled in a faint wind and their noise was like the whispering of witches, causing the hair to stir next his scalp.

Then they came into a chamber dimly lighted by the starshine streaming through open windows, and Lissa released his hand, fumbled an instant and produced a faint light of some sort. It was a glassy knob which glowed with a golden radiance. She set it on a marble table, and indicated that Amalric should recline on a couch thickly littered with silks. Groping into some mysterious recess, she produced a gold vessel of wine, and others containing food unfamiliar to Amalric. There were dates; the others, pallid and insipid to his taste, he did not recognize. The wine was pleasant to the palate, but no more heady than dish water.

Seated on a marble seat opposite him, Lissa nibbled daintily.

“What sort of place is this?” he demanded. “You are like these people—yet strangely unlike.”

“They say I am like our ancestors,” answered Lissa. “Long ago they came into the desert and built this city over a great oasis which was in reality only a series of springs. The stone they took from the ruins of a much older city—only the red tower—” her voice dropped and she glanced nervously at the star-framed windows—“only the red tower stood there. It was empty—then.

“Our ancestors, who were called Gazali, once dwelt in southern Koth. They were noted for their scholarly wisdom. But they sought to revive the worship of Mitra, which the Kothians had long ago abandoned, and the king drove them from his kingdom. They came southward, many of them, priests, scholars, teachers, scientists, with their Shemitish slaves.

“They reared Gazal in the desert; but the slaves revolted almost as soon as the city was built, and fleeing, mixed with the wild tribes of the desert. They were not illy treated—word came to them in the night—a word which sent them fleeing madly from the city into the desert.

“My people dwelt here, learning to manufacture their food and drink from such material as was at hand. Their learning was a marvel. When the slaves fled, they took with them every camel, horse and donkey in the city. There was no communication with the outer world. There are whole chambers in Gazal filled with maps and books and chronicles, but they are all nine years old at the lest; for it was nine hundred years ago that my people fled from Koth. Since then no man of the outside world has set foot in Gazal. And the people are slowly vanishing. They have become so dreamy and introspective that they have neither human passions nor ambitions. The city falls into ruins and none moves hand to repair it. Horror—” she choked and shuddered; “when horror came upon them, they could neither flee nor fight.”

“What do you mean?” he whispered, a cold wind blowing on his spine. The rustling of rotten hangings down nameless black corridors stirred dim fear in his soul.

She shook her head; she rose, came around the marble table, laid hands on his shoulders. Her eyes were wet and they shone with horror and a desperate yearning that caught at his throat. Instinctively his arm went around her lithe form, and he felt her tremble.

“Hold me!” she begged. “I am afraid! Oh, I have dreamed of such a man as you. I am not like my people; they are dead men walking forgotten streets; but I am alive. I am warm and sentient. I hunger and thirst and yearn for life. I can not abide the silent streets and ruined halls and dim people of Gazal, though I have never known anything else. That is why I ran away—I yearned for life—”

She was sobbing uncontrollably in his arms. Her hair streamed over his face; her fragrance made him dizzy. Her firm body strained against his. She was lying across his knees, her arms locked about his neck. Straining her to his breast he crushed her lips with his. Eyes, lips, cheeks, hair, throat, breasts, he showered with hot kisses, until her sobs changed to panting gasps. His passion was not the violence of a ravisher. The passion that slumbered in her woke in one overpowering wave. The glowing gold ball, struck by his groping fingers, tumbled to the floor and was extinguished. Only the starshine gleamed through the windows.

Lying in Amalric’s arms on the silk-heaped couch, Lissa opened her heart and whispered her dreams and hopes and aspirations, childish, pathetic, terrible.

“I’ll take you away,” he muttered. “Tomorrow. You are right. Gazal is a city of the dead; we will seek life and the outer world. It is violent, rough, cruel; but better that than this living death—”

The night was broken by a shuddering cry of agony, horror and despair. Its timbre brought out cold sweat on Amalric’s skin. He started upright from the couch, but Lissa clung to him desperately.

“No, no!” she begged in a frantic whisper. “Do not go! Stay!”

“But murder is being done!” he exclaimed, fumbling for his sword. The cries seemed to come from across an outer court. Mingled with them there was an indescribable tearing, rending sound. They rose higher and thinner, unbearable in their hopeless agony, then sank away in a long shuddering sob.

“I have heard men dying on the rack cry out like that!” muttered Amalric, shaking with horror. “What devil’s work is this?”

Lissa was trembling violently in a frenzy of terror. He felt the wild pounding of her heart.

“It is the Horror of which I spoke!” she whispered. “The Horror which dwells in the red tower. Long ago it came—some say it dwelt there in the lost years, and returned after the building of Gazal. It devours human beings. Bats fly from the tower. What it is, no one knows, since none have seen it and lived to tell of it. It is a god or a devil. That is why the slaves fled; why the desert people shun Gazal. Many of us have gone into its awful belly. Eventually all will have gone, and it will rule over an empty city, as men say it ruled over the ruins from which Gazal was reared.”

“Why have the people stayed to be devoured?” he demanded.

“I do not know,” she whimpered; “they dream—”

“Hypnosis,” muttered Amalric; “hypnosis coupled with decay. I saw it in their eyes. This devil has them mesmerized. Mitra, what a foul secret!”

Lissa pressed her face against his bosom and clung to him.

“But what are we to do?” he asked uneasily.

“There is nothing to do,” she whispered. “Your sword would be helpless. Perhaps It will not harm us. It has taken a victim tonight. We must wait like sheep for the butcher.”

“I’ll be damned if I will!” Amalric exclaimed, galvanized. “We will not wait for morning. We’ll go tonight. Make a bundle of food and drink. I’ll get the horse and camel and bring them to the court outside. Meet me there!”

Since the unknown monster had already struck, Amalric felt that he was safe in leaving the girl alone for a few minutes. But his flesh crawled as he groped his way down the winding corridor and through the black chambers where the swinging tapestries whispered. He found the beasts huddled nervously together in the court where he had left them. The stallion whinnied anxiously and nuzzled him, as if sensing peril in the breathless night.

He saddled and bridled and hurriedly led them through the narrow opening onto the street. A few minutes later he was standing in the starlit court. And even as he reached it, he was electrified by an awful scream which rang shudderingly upon the air. It came from the chamber where he had left Lissa.

He answered that piteous cry with a wild yell; drawing his sword he rushed across the court, hurled himself through the window. The golden ball was glowing again, carving out black shadows in the shrinking corners. Silks lay scattered on the floor. The marble seat was upset. But the chamber was empty.

A sick weakness overcame Amalric and he staggered against the marble table, the dim light waving dizzily to his sight. Then he was swept by a mad rage. The red tower! There the fiend would bear his victim!

He darted back across the court, sought the streets and raced toward the tower which glowed with an unholy light under the stars. The streets did not run straight. He cut through silent black buildings and crossed courts whose rank grass waved in the night wind.

Ahead of him, clustered about the crimson tower, rose a heap of ruins, where decay had eaten more savagely than at the rest of the city. Apparently none dwelt among them. They reeled and tumbled, a crumbling mass of quaking masonry, with the red tower rearing up among them like a poisonous red flower from charnel house ruin.

To reach the tower he would be forced to traverse the ruins. Recklessly he plunged into the black mass, groping for a door. He found one and entered, thrusting his sword ahead of him. Then he saw such a vista as men sometimes see in fantastic dreams. Far ahead of him stretched a long corridor, visible in a faint unhallowed glow, its black walls hung with strange shuddersome tapestries. Far down it he saw a receding figure—a white, naked, stooped figure, lurching along, dragging something the sight of which filled him with sweating horror. Then the apparition vanished from his sight, and with it vanished the eery glow. Amalric stood in the soundless dark, seeing nothing, hearing nothing; thinking only of a stooped white figure that dragged a limp human down a long black corridor.

As he groped onward, a vague memory stirred in his brain—the memory of a grisly tale mumbled to him over a dying fire in the skull-heaped devil-devil hut of a black witchman—a tale of a god which dwelt in a crimson house in a ruined city and which was worshipped by darksome cults in dank jungles and along sullen dusky rivers. And there stirred, too, in his mind, an incantation whispered in his ear in awed and shuddering tones, while the night had held its breath, the lions had ceased to roar along the river, and the very fronds had ceased their scraping one against the other.

Ollam-onga, whispered a dark wind down the sightless corridor. Ollam-onga whispered the dust that ground beneath his stealthy feet. Sweat stood on his skin and the sword shook in his hand. He stole through the house of a god, and fear held him in its bony hand. The house of the god—the full horror of the phrase filled his mind. All the ancestral fears and the fears that reached beyond ancestry and primordial race-memory crowded upon him; horror cosmic and unhuman sickened him. His weak humanity crushed him in its realization as he went through the house of darkness that was the house of a god.

About him shimmered a glow so faint it was scarcely discernable; he knew that he was approaching the tower itself. Another instant and he groped his way through an arched door and stumbled upon strangely spaced steps. Up them he went, and as he climbed that blind fury which is mankind’s last defense against diabolism and all the hostile forces of the universe, surged in him, and he forgot his fear. Burning with terrible eagerness, he climbed up and up through the thick evil darkness until he came into a chamber lit by a weird glow.

And before him stood a white naked figure. Amalric halted, his tongue cleaving to his palate. It was a naked white man, to all appearances, which stood gazing at him, mighty arms folded on an alabaster breast. The features were classic, cleanly carven, with more than human beauty. But the eyes were balls of luminous fire, such as never looked from any human head. In those eyes Amalric glimpsed the frozen fires of the ultimate hells, touched by awful shadows.

Then before him the form began to grow dim in outline; to waver—with a terrible effort the Aquilonian burst the bonds of silence and spoke a cryptic and awful incantation. And as the frightful words cut the silence, the white giant halted—froze—again his outlines stood out clear and bold against the golden background.

“Now fall on, damn you!” cried Amalric hysterically. “I have bound you into your human shape! The black wizard spoke truly! It was the master word he gave me! Fall on, Ollam-onga—till you break the spell by feasting on my heart, you are no more than a man like me!”

With a roar that was like the gust of a black wind, the creature charged. Amalric sprang aside from the clutch of those hands whose strength was more than that of the whirlwind. A single taloned finger, spread wide and catching in his tunic, ripped the garment from him like a rotten rag as the monster plunged by. But Amalric, nerved to more than human quickness by the horror of the fight, wheeled and drove his sword through the thing’s back, so that the point stood out a foot from the broad breast.

A fiendish howl of agony shook the tower; the monster whirled and rushed at Amalric, but the youth sprang aside and raced up the stairs to the dais. There he wheeled and catching up a marble seat, hurled it down upon the horror that was lumbering up the stairs. Full in the face the massive missile struck, carrying the fiend back down the steps. He rose, an awful sight, streaming blood and again essayed the stairs. In desperation Amalric lifted a jade bench whose weight wrenched a groan of effort from him, and hurled it.

Beneath the impact of the hurtling bulk Ollam-onga pitched back down the stair and lay among the marble shards, which were flooded with his blood. With a last desperate effort, he heaved himself up on his hands, eyes glazing, and throwing back his bloody head, voiced an awful cry. Amalric shuddered and recoiled from the abysmal horror of that scream. And it was answered. From somewhere in the air above the tower a faint medley of fiendish cries came back like an echo. Then the mangled white figure went limp among the blood-stained shards. And Amalric knew that one of the gods of Kush was no more. With the thought came blind, unreasoning horror.

In a fog of terror he rushed down the stair, shrinking from the thing that lay staring in the floor. The night seemed to cry out against him, aghast at the sacrilege. Reason, exultant over his triumph, was submerged in a flood of cosmic fear.

As he put foot on the head of the steps, he halted short. Up from the darkness Lissa came to him, her white arms outstretched, her eyes pools of horror.

“Amalric!” it was a haunting cry. He crushed her in his arms.

“I saw It,” she whimpered—“dragging a dead man through the corridor. I screamed and fled; then when I returned, I heard you cry out, and knew you had gone to search for me in the red tower—”

“And you came to share my fate,” his voice was almost inarticulate. Then as she tried to peer in trembling fascination past him, he covered her eyes with his hands and turned her about. Better that she should not see what lay on the crimson floor. As he half led, half carried her down the shadowed stairs, a glance over his shoulder showed him that a naked white figure lay no longer lay among the broken marble. The incantation had bound Ollam-onga into his human form in life, but not in death. Blindness momentarily assailed Amalric, then, galvanized into frantic haste, he hurried Lissa down the stairs and through the dark ruins.

He did not slacken pace until they reached the street where the camel and stallion huddled against one another. Quickly he mounted the girl on the camel, and he swung up on the stallion. Taking the lead-line, he headed straight for the broken wall. A few minutes later he breathed gustily. The open air of the desert cooled his blood; it was free of the scent of decay and hideous antiquity.

There was a small water-pouch hanging from his saddle bow. They had no food, and his sword was in the chamber in the red tower. He had not dared touch it. Without food and unarmed, they faced the desert; but its peril seemed less grim than the horror of the city behind them.

Without speaking they rode. Amalric headed south; somewhere in that direction there was a water hole. Just at dawn, as they mounted a crest of sand, he looked back toward Gazal, unreal in the pink light. And he stiffened and Lissa cried out. Out of a breach in the wall rode seven horsemen; their steeds were black, and the riders were cloaked in black from head to foot. There had been no horses in Gazal. Horror swept over Amalric, and turning, he urged their mounts on.

The sun rose, red, and then gold, and then a ball of white beaten flame. On and on the fugitives pressed, reeling with heat and fatigue, blinded by the glare. They moistened their lips with water from time to time. And behind at an even pace, rode seven black dots. Evening began to fall, and the sun reddened and lurched toward the desert rim. And a cold hand clutched Amalric’s heart. The riders were closing in. As darkness came on, so came the black riders. Amalric glanced at Lissa, and a groan burst from him. His stallion stumbled and fell. The sun had gone down, the moon was blotted out suddenly by a bat-shaped shadow. In the utter darkness the stars glowed red, and behind him Amalric heard a rising rush as of an approaching wind. A black speeding clump bulked against the night, in which glinted sparks of awful light.

“Ride, girl!” he cried despairingly. “Go on—save yourself; it is me they want!”

For answer she slid down from the camel and threw her arms about him.

“I will die with you!”

Seven black shapes loomed against the stars, racing like the wind. Under the hoods shone balls of evil fire; flesh jaw bones seemed to clack together. Then there was an interruption; a horse swept past Amalric and the horse, a vague bulk in the unnatural darkness. There was the sound of an impact as the unknown steed caromed among the oncoming shapes. A horse screamed frenziedly, and a bull like voice bellowed in a strange tongue. From somewhere in the night a clamor of yells answered.

There was some sort of violent action taking place. Horse’s hoofs stamped and clattered, there was the impact of savage blows, and the same stentorian voice was cursing lustily. Then the moon abruptly came out and lit a fantastic scene.

A man on a giant horse whirled, slashed and smote apparently at thin air, and from another direction swept a wild horde of riders, their curved swords flashing in the moon light. Away over the crest of a rise seven black figures were vanishing, their cloaks floating out like the wings of bats.

Amalric was swamped by wild men who leaped from their horses and swarmed around him. Sinewy naked arms pinioned him, fierce brown hawk-like faces snarled at him. Lissa screamed. Then the attackers were thrust right and left as the man on the great horse reined through the crowd. He bent from his saddle, glared closely at Amalric.

“The devil!” he roared; “Amalric the Aquilonian!”

“Conan!” Amalric exclaimed bewilderedly. “Conan! Alive!”

“More alive than you seem to be,” answered the other. “By Crom, man you look as if all the devils in this desert had been hunting you through the night. What things were those pursuing you? I was riding around the camp my men had pitched, to make sure no enemies were in hiding, when the moon went out like a candle, and then I heard sounds of flight. I rode toward the sounds, and by Crom, I was among those devils before I knew what was happening. I had my sword in my hand and I laid about me—by Crom, their eyes blazed like fire in the dark! I know my edge bit them, but when the moon came out, they were gone like a puff of wind. Were they men or fiends?”

“Ghouls sent up from Hell,” shuddered Amalric. “Ask me no more; some things are not to be discussed.”

Conan did not press the matter, nor did he look incredulous. His beliefs included night fiends, ghosts, hobgoblins and dwarfs.

“Trust you to find a woman, even in a desert,” he said, glancing at Lissa, who had crept to Amalric and was clinging close to him, glancing fearfully at the wild figures which hemmed them in.

“Wine!” roared Conan. “Bring flasks! Here!” He seized a leather flask from those thrust out to him, and placed it in Amalric’s hand. “Give the girl a swig, and drink some yourself,” he advised. “Then we’ll put you on horses and take you to the camp. You need food, rest and sleep. I can see that.”

A richly caparisoned horse was brought, rearing and prancing, and willing hands helped Amalric into the saddle; then the girl was handed up to him, and they moved off southward, surrounded by the wiry brown riders in their picturesque semi-nakedness. Conan rode ahead, humming a riding song of the mercenaries.

“Who is he?” whispered Lissa, her arms about her lover’s neck; he was holding her on the saddle in front of him.

“Conan, the Cimmerian,” muttered Amalric. “The man I wandered with in the desert after the defeat of the mercenaries. These are the men who struck him down. I left him lying under their spears, apparently dead. Now we meet him obviously in command of, and respected by them.”

“He is a terrible man,” she whispered.

He smiled. “You never saw a white-skinned barbarian before. He is a wanderer and a plunderer, and a slayer, but he has his own code of morals. I don’t think we have anything to fear from him.”

In his heart he was not sure. In a way, it might be said that he had forfeited Conan’s comradeship when he had ridden away into the desert, leaving the Cimmerian senseless on the ground. But he had not known that Conan was not dead. Doubt haunted Amalric. Savagely loyal to his companions, the Cimmerian’s wild nature saw no reason why the rest of the world should not be plundered. He lived by the sword. And Amalric suppressed a shudder as he thought of what might chance did Conan desire Lissa.

Later on, having eaten and drunk in the camp of the riders, Amalric sat by a small fire in front of Conan’s tent; Lissa, covered with a silken cloak, slumbered with her curly head on his knees. And across from him the fire light played on Conan’s face, interchanging lights and shadows.

“Who are these men?” asked the young Aquilonian.

“The riders of Tombalku,” answered the Cimmerian.

“Tombalku!” exclaimed Amalric. “Then it is no myth!”

“Far from it!” agreed Conan. “When my accursed steed fell with me, I was knocked senseless, and when I recovered consciousness, the devils had me bound hand and foot. This angered me, so I snapped several of the cords they had me tied with, but they rebound them as fast as I could break them—never did I get a hand entirely free. But to them my strength seemed remarkable—”

Amalric gazed at Conan unspeaking. The man was tall and broad as Tilutan had been, without the black man’s surplus flesh. He could have broken the Ghanata’s neck with his naked hands.

“They decided to carry me to their city instead of killing me out of hand,” Conan went on. “They thought a man like me should be a long time in dying by torture, and so give them sport. Well, they bound me on a horse without a saddle, and we went to Tombalku.

“There are two kings of Tombalku. They took me before them—a lean brown-skinned devil named Zehbeh, and a big fat negro who dozed on his ivory-tusk throne. They spoke a dialect I could understand a little, it being much like that of the western Mandingo who dwell on the coast. Zehbeh asked a brown priest, Daura, what should be done with me, and Daura cast dice made of sheep bone, and said I should be flayed alive before the altar of Jhil. Every one cheered and that woke the negro king.

“I spat on Daura and cursed him roundly, and the kings as well, and told them that if I was to be skinned, by Crom, I demanded a good bellyfull of wine before they began, and I damned them for thieves and cowards and sons of harlots.

“At this the black king roused and sat up and stared at me, and then he rose and shouted: ‘Amra!’ and I knew him—Sakumbe, a Suba from the Black Coast, a fat adventurer I had known well in the days when I was a corsair along that coast. He trafficked in ivory, gold dust and slaves, and would cheat the devil out of his eye-teeth—well, when he knew me, he descended from his throne and embraced me for joy—the black, smelly devil—and took my cords off me with his own hands. Then he announced that I was Amra, the Lion, his friend, and that no harm should come to me. Then followed much discussion, because Zehbeh and Daura wanted my hide. But Sakumbe yelled for his witch-finder, Askia, and he came, all feathers and bells and snake-skins—a wizard of the Black Coast, and a son of the devil if there ever was one.

“Askia pranced and made incantations, and announced that Sakumbe was the chosen of Agujo, the Dark One, and all the black people of Tombalku shouted, and Zehbeh backed down.

“For the blacks in Tombalku are the real power. Several centuries ago the Aphaki, a Shemitish race, pushed into the southern desert and established the kingdom of Tombalku. They mixed with the desert-blacks and the result was a brown straight-haired race, which is still more white than black. They are the dominant caste in Tombalku, but they are in the minority, and a pure black king always sits on the throne beside the Aphaki ruler.

“The Aphaki conquered the nomads of the southwestern desert, and the negro tribes of the steppes which lie to the south of them. These riders, for instance, are Tibu, of mixed Stygian and negro blood.

“Well, Sakumbe, through Askia, is the real ruler of Tombalku. The Aphaki worship Jhil, but the blacks worship Ajujo the Dark One, and his kin. Askia came to Tombalku with Sakumbe, and revived the worship of Ajujo, which was crumbling because of the Aphaki priests. Askia made black magic which defeated the wizardry of the Aphaki, and the blacks hailed him as a prophet sent by the dark gods. Sakumbe and Askia wax as Zehbeh and Daura wane.

“Well, as I am Sakumbe’s friend, and Askia spoke for me, the blacks received me with great applause. Sakumbe had Kordofo, the general of the horsemen, poisoned, and gave me his place, which delighted the blacks and exasperated the Aphaki.

“You will like Tombalku! It was made for men like us to loot! There are half a dozen powerful factions plotting and intriguing against each other—there are continual brawls in the taverns and streets, secret murders, mutilations, and executions. And there are women, gold, wine—all that a mercenary wants! And I am high in favor and power! By Crom, Amalric, you could not come at a better time! Why, what’s the matter? You do not seem as enthusiastic as I remember you having once been in such matters.”

“I crave your pardon, Conan,” apologized Amalric. “I do not lack interest, but weariness and want of sleep overcomes me.”

But it was not gold, women and intrigue that the Aquilonian was thinking, but of the girl who slumbered on his lap; there was no joy in the thought of taking her into such a welter of intrigue and blood as Conan had described. A subtle change had come over Amalric, almost without his knowledge.