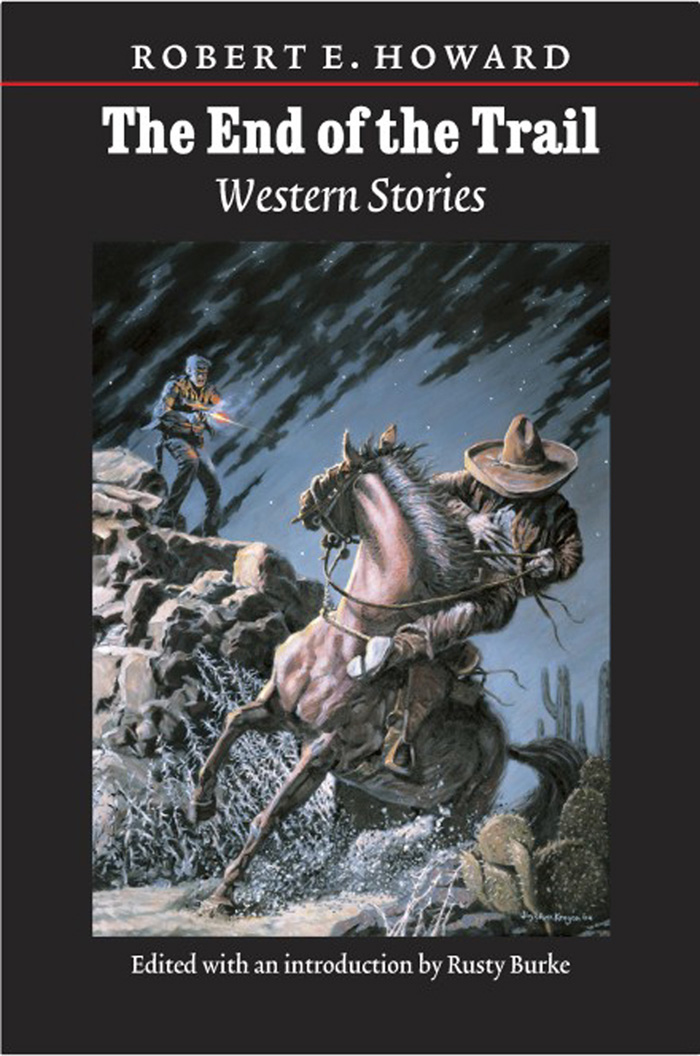

Cover from the collection The End of the Trail: Western Stories (2005).

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

Published in The Cross Plains Review, November 1928—January 1929 (in 9 parts),

though here taken from the 2005 collection The End of the Trail: Western Stories, which includes emendations from

the incomplete original typescript provided by Glenn Lord.

| Chapter 1. The Wanderer Chapter 2. Mystery Chapter 3. The Girl’s Story |

Chapter 4. A Trail of Blood Chapter 5. Thundering Cliffs |

“Now, come all you punchers, and listen to my tale,

“When I tell you of troubles on the Chisholm Trail!”

Steve Harmer was riding Texas-fashion, slow and easy, one knee hooked over the saddle horn, hat pulled over his brows to shade his face. His lean body swayed rhythmically to the easy gait of his horse.

The trail he was following sloped gradually upward, growing steeper as he continued. Cedars flanked the narrow path, with occasional pinons and junipers. Higher up, these gave place to pines.

Looking back, Steve could see the broad level country he had left, deeply grassed and sparsely treed. Beyond and above, the timbered slopes of the mountains frowned. Peak beyond peak, pinnacle beyond pinnacle they rose, with great undulating slopes between, as if piled by giants.

Suddenly behind the lone rider came the clatter of hoofs. Steve pulled aside to let the horsemen by, but they came to a halt beside him. Steve swept off his broad-brimmed hat.

There were two of the strangers, and one was a girl. To Steve she seemed strangely out of place, somehow, in this primitive setting. She sat her horse in an unfamiliar manner and her whole air was not of the West. She wore an Eastern riding habit—and then Steve forgot her clothes as he looked at her face. A vagrant curl, glinting gold in the sun, fell over her white forehead and from beneath this two soft grey eyes looked at him. Her full lips were half parted—

Å“Say, you!” a rough voice jarred Steve out of his daydreams.

The girl’s companion was as characteristically Western as she was not. He was a heavily built man of middle life, thickly bearded and roughly clad. His features were dark and coarse, and Steve noted the heavy revolver which hung at his hip.

This man spoke in a harsh, abrupt manner.

“Who’re you and where do you reckon you’re goin’?”

Steve stiffened at the tone. He shot a glance at the girl, who seemed rather pale and frightened.

“My name’s Harmer,” said he, shortly. Å“I’m just passin’ through.”

“Yeah?” the bearded lips parted in a wolfish grin. Å“I reckon, stranger, you done lost your way—you shoulda took that trail back yonder a ways that branched off to the south.”

“I ain’t said where I was goin’,” Steve responded, nettled. Å“Maybe I have reason for goin’ this way.”

“That’s what I’m thinkin’,” the bearded man answered, and Steve sensed the menacing note in his voice. Å“But you may have reason for takin’ the other trail yet. Nobody lives in these hills, and they don’t like strangers! Be warned, young feller, and don’t git into somethin’ you don’t know nothin’ about.”

And while Steve gaped at him, not understanding, the man flung a curt order to the girl, and they both sped off up the trail, their horses laboring under the stress of quirt and spur. Steve watched in amazement.

“By golly, they don’t care how they run their broncs uphill. What do you reckon all that rigamarole meant? Maybe I oughta taken the other trail, at that—golly, that was a pretty girl!”

The riders disappeared on the thickly timbered slope and Steve, after some musing, nudged his steed with his knee and started on.

“I’m a goin’ West and punch Texas cattle!

“Ten dollar horse and forty dollar saddle.”

Crack! A sharp report cut through the melody of his lazy song. A flash of fire stabbed from among trees further up the slope. Steve’s hat flew from his head, his horse snorted and reared, nearly unseating his rider.

Steve whirled his steed, dropping off on the far side. His gun was in his hand as he peered cautiously across his saddle in the direction from which the shot had come. Silence hovered over the tree-masked mountain side and no motion among the intertwining branches betrayed the presence of the hidden foe.

At last Steve cautiously stepped from behind his horse. Nothing happened. He sheathed his gun, stepped forward and recovered his hat, swearing as he noted the neat hole through the crown.

“Now did that whiskered galoot stop up there some place and sneak back for a crack at me?” he wondered. Å“Or did he tell somebody else to—or did that somebody else do it on their own idea? And what is the idea? What’s up in them hills that they don’t want seen? And was this sharpshooter tryin’ to kill me or just warn me?”

He shook his head and shrugged his shoulders.

Å“Anyway,” he meditated as he mounted, Å“I reckon that south trail is the best road, after all.”

The south branch, he found, led down instead of up, skirting the base of the incline. He sighted several droves of sheep, and as the sun sank westward, he came upon a small cabin built near a running stream of clear water.

Å“Hi yah! Git down and set!” greeted the man who came to the door.

He was a small, wizened old fellow, remarkably bald, and he seemed delighted at the opportunity for conversation which Steve’s coming afforded. But Steve eyed him with a suspicious glance before he dismounted.

Å“My name is Steve Harmer,” said Steve abruptly. Å“I’m from Texas and I’m just passin’ through. If you hone for me to ride on, just say so and they won’t be no need for slingin’ lead at me.”

Å“Heh, heh!” laughed the old fellow. Å“Son, I kin read yore brand! You done fell in with my neighbors of the Sunset Mountains!”

Å“A tough lookin’ hombre and a nice lookin’ girl,” admitted Steve. “And some fellow who didn’t give his name, but just ruined my best hat.”

Å“Light!” commanded the old man. “Light and hobble yore bronc. This ain’t no hotel, but maybe you can struggle along with the accommodations. My name is ... Å‘Hard Luck Harper,’ and I aim to live up to that handle. You ain’t by no chance got no corn juice in them saddle bags?”

“No, I ain’t,” answered Steve, dismounting.

Å“I was afeard not,” sighed the old man. Å“Hard Luck I be to the end—come in—I smell that deer meat a-burnin’.”

After a supper of venison, sourdough bread and coffee, the two sat on the cabin stoop and watched the stars blink out as they talked. The sound of Steve’s horse, cropping the luxuriant grass, came to them, and a night breeze wafted the spicy scents of the forest.

Å“This country is sure different from Texas,” said Steve. Å“I kinda like these mountains, though. I was figurin’ on campin’ up among ’em tonight, that’s why I took that west trail. She goes on to Rifle Pass, don’t she?”

Å“She don’t,” replied the old man. Å“Rifle Pass is some south of here and this is the trail to that small but thrivin’ metropolis. That trail you was followin’ meanders up in them hills and where she goes, nobody knows.”

Å“Why don’t they?”

Å“Fer two reasons. The first is, they’s no earthly reason fer a man in his right mind to go up there, and I’ll refer you to yore hat fer the second.”

“What right has this bird got to bar people from these mountains?”

“I think it must be a thirty-thirty caliber,” grinned the old man. Å“That feller you met was Gila Murken, who lays out to own them mountains, like, and the gal was his niece, I reckon, what come from New York.

“I dunno what Gila’s up to. I’ve knowed him, off and on, fer twenty years, and never knowed nothin’ good. I’m his nearest neighbor, now, but I ain’t got the slightest idee where his cabin is—up there somewhere.” He indicated the gigantic brooding bulk of the Sunset Mountains, black in the starlight.

“Gila’s got a couple fellers with him, and now this gal. Nobody else ever goes up that hill trail. The men come up here a year ago.”

Steve mused. Å“An’ what do you reckon is his idee for discouragin’ visitors?”

The old man shrugged his shoulders and shook his head. “Son, I’ve wondered myself. He and his pards lives up in them mountains and regular once a week one of ’em rides to Rifle Pass or maybe clean to Stirrup, east. They have nothin’ to do with me or anybody else. I’ve wondered, but, gosh, they ain’t a chance!”

“Ain’t a chance of what?”

“Steve,” said Hard Luck, his lean hand indicating the black vastness of the hills, Å“somewhere up there amongst them canyons and gorges and cliffs, is a fortune! And sometimes I wonder if Gila Murken ain’t found it.

“It’s forty year ago that me and Bill Hansen come through this country—first white men in it, so far as I know. I was nothin’ but a kid then an’ we was buffalo hunters, kinda strayed from the regular course.

“We went up into them hills, Sunset Mountains, the Indians call ’em, and away back somewheres we come into a range of cliffs. Now, it don’t look like it’d be that way, lookin’ from here, but in among the mountains they’s long chains of cliffs, straight up and down, maybe four hundred feet high, clay and rock—mighty treacherous stuff. They’s maybe seventeen sets of these cliffs, Ramparts, we call ’em, and they look just alike. Trees along the edge, thick timber at the base. The edges is always crumblin’ and startin’ landslides and avalanches.

“Me and Bill Hansen come to the front of one of these Ramparts and Bill was lookin’ at where the earth of the cliff face had kinda shelved away when he let out a whoop!

“Gold! Reef gold—the blamedest vein I ever see, just lying there right at the surface ready for somebody to work out the ore and cart it off! We dropped our guns and laid into the cliff with our fingernails, diggin’ the dirt away. And the vein looked like she went clear to China! Get that, son, reef gold and quartz in the open cliff face.

“ ‘Bill,’ says I, Å‘we’re milyunaires!’

“And just as I said it, somethin’ came whistlin’ by my cheek and Bill gave one yell and went down on his face with a steel-pointed arrow through him. And before I could move a rifle cracked and somethin’ that felt like a red hot hammer hit me in the chest and knocked me flat.

“A war party—they’d stole up on us while we was diggin’. Cheyennes they was, from the north, and they come out and chanted their scalp songs over us. Bill was dead and I lay still, all bloody but conscious, purtendin’ I was a stiff, too.

“They scalped Bill and they scalped me—”

Steve gave an exclamation of horror.

“Oh, yes,” said Hard Luck tranquilly. Å“It hurt considerable—fact is, I don’t know many things that hurt wuss. But somehow I managed to lie still and not let on like I was alive, though a couple of times I thought I was goin’ to let out a whoop in spite of myself.”

“Did they scalp you plumb down to the temples?” asked Steve morbidly.

“Naw—the Cheyennes never scalped that way.” Hard Luck ran his hand contemplatively over his glistening skull. “They just cut a piece out of the top—purty good sized piece, though—and the rest of the ha’r kinda got discouraged and faded away, after a few years.

“Anyway, they danced and yelled fer awhile an’ then they left an’ I began to take invoice to see if I was still livin’. I was shot through the chest but by some miracle the ball had gone on through without hitting anything important. I thought, though, I was goin’ to bleed to death. But I stuffed the wound with leaves and the webs these large white spiders spin on the low branches of trees. I crawled to a spring which wasn’t far away and lay there like a dead man till night, when I came to and lay there thinkin’ about my dead friend, and my wounds and the gold I’d never enjoy.

“Then, I got out of my right mind and went crawlin’ away through the forest, not knowin’ why I did it. I was just like a man that’s drunk: I knowed what I was doin’ but I didn’t know why I was doin’ it. I crawled and I crawled and how long I kept on crawlin’ I don’t know fer I passed clean out, finally, and some buffalo hunters found me out in the level country, miles and miles from where I was wounded. I was ravin’ and gibberin’ and nearly dead.

“They tended to me and after a long time my wounds healed and I come back to my right mind. And when I did, I thought about the gold and got up a prospectin’ party and went back. But seems like I couldn’t remember what all happened just before I got laid out. Everything was vague and I couldn’t remember what way Bill and me had taken to get to the cliff, and I couldn’t remember how it looked. They’d been a lot of landslides, too, and likely everything was changed in looks.

“Anyway, I couldn’t find the lost mine of Sunset Mountain, and though I been comin’ every so often and explorin’ again, for forty years me nor no other livin’ man has ever laid eyes on that gold ledge. Some landslide done covered it up, I reckon. Or maybe I just ain’t never found the right cliff. I don’t know.

“I done give it up. I’m gettin’ old. Now I’m runnin’ a few sheep and am purty contented. But you know now why they call me Hard Luck.”

Å“And you think that maybe this Murken has found your mine and is workin’ it on the sly?”

“Naw, really I don’t. T’wouldn’t be like Gila Murken to try to conceal the fact—he’d just come out and claim it and dare me to take it away from him. Anyway,” the old man continued with a touch of vanity, Å“no dub like Gila Murken could find somethin’ that a old prospector like me has looked fer, fer forty year without findin’, nohow.”

Silence fell. Steve was aware that the night wind, whispering down from the mountains, carried a strange dim throbbing—a measured, even cadence, haunting and illusive.

“Drums,” said Hard Luck, as if divining his thought. Å“Indian drums; tribe’s away back up in the mountains. Nothin’ like them that took my scalp. Navajoes, these is, a low class gang that wandered up from the south. The government give ’em a kind of reservation back in the Sunset Mountains. Friendly, I reckon—trade with the whites a little.

“Them drums is been goin’ a heap the last few weeks. Still nights you can hear ’em easy; sound travels a long way in this land.”

His voice trailed off into silence. Steve gazed westward where the monstrous shadowy peaks rose black against the stars. The night breeze whispered a lonely melody through the cedars and pines. The scent of fresh grass and forest trees was in his nostrils. White stars twinkled above the dark mountains and the memory of a pretty, wistful face floated across Steve’s vision. As he grew drowsy, the face seemed nearer and clearer, and always through the mists of his dreams throbbed faintly the Sunset drums.

Steve drained his coffee cup and set it down on the rough-hewn table.

“I reckon,” said he, “for a young fellow you’re a pretty good cook—Hard Luck, I been thinkin’.”

“Don’t strain yoreself, son. It ain’t a good idee startin’ in on new things, at this time of yore life—what you been thinkin’ about?”

“That mine of yours. I believe, instead of goin’ on to Rifle Pass like I was thinkin’ of doin’, I’ll lay over a few days and look for that lost gold ledge.”

“Considerin’ as I spent the best part of my life huntin’ it,” said Hard Luck testily, “it’s very likely you’ll stub yore toes on it the first thing. The Lord knows, I’d like to have you stay here as long as you want. I don’t see many people. But they ain’t one chance in a hundred of you findin’ that mine, and I’m tellin’ you, it ain’t healthy to ramble around in the Sunsets now, with Gila Murken hatchin’ out the Devil only knows what, up there.”

“Murken owes me a new hat,” said Steve moodily. Å“And furthermore and besides it’s time somebody showed him he ain’t runnin’ this country. I crave to hunt for that mine. I dreamed about it last night.”

Å“You better forgit that mountain-business and work with me here on my ranch,” advised Hard Luck. Å“I’ll give you a job of herdin’ sheep.”

“Don’t get insultin’,” said Steve reprovingly. “How far up in them hills can a horse go?”

“You can navigate most of ’em on yore bronc if you take yore time an’ let him pick his way. But you better not.”

In spite of Hard Luck’s warning, Steve rode up the first of the great slopes before the sun had risen high enough for him to feel its heat. It was a beautiful morning; the early sunlight glistened on the leaves of the trees and on the dew on the grass. Above and beyond him rose the slopes, dark green, deepening into purple in the distance. Snow glimmered on some of the higher peaks.

Steve felt a warmth of comfort and good cheer. The fragrance of Hard Luck’s coffee and flapjacks was still on his palate, and the resilience of youth sang through his veins. Somewhere up there in the mysterious tree-clad valleys and ridges adventure awaited him, and as Steve rode, the lost mine of the Sunsets was least in his thoughts.

No trail led up the way he took, but his horse picked his route between boulders and cedars, climbing steep slopes as nimbly as a mountain goat. The cedars gave way to pines and occasionally Steve looked down into some small valley, heavily grassed and thickly wooded. The sun was slanting toward the west when he finally pulled up his horse on the crest of a steep incline and looked down.

A wilder and more broken country he had never seen. From his feet the earth sloped steeply down, covered with pines which seemed to cling precariously, to debouch into a sort of plateau. On three sides of this plateau rose the slanting sides of the mountains. The fourth or east side fell away abruptly into cliffs which seemed hundreds of feet high. But what drew Steve’s gaze was the plateau itself.

Near the eastern cliffs stood two log cabins. Smoke curled from one, and as Steve watched, a man came out of the door. Even at that distance Steve recognized the fellow whom Hard Luck had designated as Gila Murken.

Steve slipped from the saddle, led his horse back into the pines a short distance and flung the reins over a tree limb. Then he stole back to the crest of the slope. He did not think Murken could see him, hidden as he was among the trees, but he did not care to take any chances. Another man had joined Murken and the two seemed to be engaged in conversation. After awhile they turned and went into the second cabin.

Time passed but they did not emerge. Suddenly Steve’s heart leaped strangely. A slim girlish form had come from the cabin out of which the men had come, and the sunshine glinted on golden hair. Steve leaned forward eagerly, wondering why the mere sight of a girl should cause his breath to come quicker.

She walked slowly toward the cliffs and Steve perceived that there was what seemed to be a deep gorge, presumably leading downward. Into this the girl disappeared. Steve now found that the mysterious cabins had lost much of their interest, and presently he went back to his horse, mounted and rode southward, keeping close to the crest of the slopes. At last he attained a position where he could look back at the plateau and get a partial view of the cliffs. He decided that they were some of the Ramparts, spoken of by Hard Luck. They rose steep and bare for four hundred feet, deeply weathered and serrated. Gorges cut deep into them and promontories stood out over the abysses beneath. Great boulders lined the edge of the precipices and the whole face of the cliffs looked unstable and treacherous.

At the foot, tall forest trees masked a rough and broken country. And as he looked Steve saw the girl, a tiny figure in the distance, come out into a clearing. He watched her until she vanished among the trees, and then turned his steed and rode back in the direction from which he had come, though not following the same route. He took his time, riding leisurely.

The sun slanted westward as he came to the lower slopes and looked back to see the rim of the Ramparts jutting below the heights he had left. He had made a vast semicircle and now the cliffs were behind and above him, instead of in front and below.

He went his leisurely way and suddenly he was aware of voices among the cedars in front of him. He slipped from his saddle, dropped the reins to the horse’s feet and stole forward. Hidden among the undergrowth, he looked into a small glade where stood two figures—the girl of the cliffs and a tall lanky man.

“No! No!” the girl was saying. Å“I don’t want to have anything to do with you. Go away and let me alone or I’ll tell my uncle.”

Å“Haw! Haw!” The man’s laugh was loud but mirthless. Å“Yore uncle and me is too close connected in a business way for him to rile me! I’m tellin’ you, this ain’t no place for you and you better let me take you away to whar there’s people and towns and the like.”

“I don’t trust you,” she answered sullenly.

“Aw, now don’t you? Come on—admit you done come down here just to meet me!”

“That’s a lie!” the girl cried, stung. Å“You know I just went for a stroll; I didn’t know you were here.”

“These mountains ain’t no place for a Å‘stroll.’ ”

“My uncle won’t let me have a horse and ride, unless he’s with me. He’s afraid I’ll run away.”

“And wouldn’t you?”

“I don’t know. I haven’t anywhere to go. But I’d about as soon die as stay here much longer.”

“Then let me take you away! I’ll marry you, if you say so. They’s many a gal would jump to take Mark Edwards up on that deal.”

“Oh, let me alone! I don’t want to marry you, I don’t want to go away with you, I don’t even want to look at you! If you really want to make a hit with me, go somewhere and shoot yourself!”

Edwards’ brow darkened.

“Oh ho, so I ain’t good enough for you, my fine lady. Reckon I’ll just take a kiss anyhow.”

His grimed hands shot and closed on her shoulders. Instantly she clenched a small fist and struck him in the mouth, so that blood trickled from his lips. The blow roused all the slumbering demon in the man.

“Yore a spit-fire,” he grunted. Å“But I ’low I’ll tame you.”

He pinioned her arms, cursed soulfully as she kicked him on the shins, and crushed her slim form to him. His unshaven lips were seeking hers when Steve impulsively went into action.

He bounded from his covert, gripped the man’s shoulder with steely fingers and swung him around, smashing him in the face with his left hand as he did so. Edwards gaped in astonishment, then roared and rushed in blindly, fingers spread to gouge and tear. Steve was not inclined to clinch rough-and-tumble fashion. He dropped his right fist nearly to his ankle and then brought it up in a long sweeping arc that stopped at Edwards’s chin. That worthy’s head went back as if it were hinged and his body, following the motion, crashed to the leaf-covered earth. He lay as if in slumber, his limbs tossed about in a careless and nonchalant manner. Steve caressed his sore knuckles and glanced at the girl.

“Is—is—is he dead?” she gasped, wide eyed.

“Naw, miss, I’m afraid he ain’t,” Steve answered regretfully. “He’s just listenin’ to the cuckoo birds. Shall I tie him up?”

“What for?” she asked reasonably enough. “No, let’s go before he comes to.”

And she started away hurriedly. Steve got his horse and followed her, overtaking her within a few rods. He walked beside her, leading his steed, his eyes admiringly taking in the proud, erect carriage of her slim figure, and the faint delicate rose-leaf tint of her complection.

“I hope you won’t think I’m intrudin’ where I got no business,” said the Texan apologetically. “But I’m a seein’ you to wherever you’re goin’. That bird might follow you or you might meet another one like him.”

“Thank you,” she answered in a rather subdued voice. “You were very kind to help me, Mr. Harmer.”

“How’d you know my name?”

“You told my uncle who you were yesterday, don’t you remember?”

“Seems like I recollect, now,” replied Steve, experiencing a foolish warm thrill that she should remember his name. “But I don’t recall you saying what your name was.”

“My name is Joan Farrel. I’m staying here with my uncle, Mr. Murken, the man with whom you saw me yesterday.”

“And was it him,” asked Steve bluntly, “that shot a hole in my hat?”

Her eyes widened; a frightened look was evident in her face.

“No! No!” she whispered. “It couldn’t have been him! He and I rode right up on to the cabin after we passed you. I heard the shot but I had no idea anyone was shooting at you.”

Steve laughed, rather ashamed of having mentioned it to the girl.

Å“Aw, it wasn’t nothin’. Likely somebody done it for a joke. But right after you-all went on, somebody cracked down on me from the trees up the trail a ways and plumb ruint my hat.”

“It must have been Edwards,” she said in a frightened voice. Å“We met him coming down the trail on foot after we’d gotten out of sight of you, and Uncle stopped and said something to him I couldn’t hear, before we went on.”

Å“And who is Edwards?”

“He’s connected with my uncle’s business in some way; I don’t know just how. He and a man named Allison camp up there close to our cabin.”

“What is your uncle’s business?” asked Steve with cool assumption.

She did not seem offended at the question.

“I don’t know. He never tells me anything. I’m afraid of him and he don’t love me.”

Her face was shadowed as if by worry or secret fear. Something was haunting her, Steve thought. Nothing more was said until they had reached the base of the cliffs. Steve glanced up, awed. The great walls hung threateningly over them, starkly and somberly. To his eye the cliffs seemed unstable, ready to crash down upon the forest below at the slightest jar. Great boulders jutted out, half embedded in the clay. The brow of the cliff, fringed with trees, hung out over the concave walls.

From where he stood Steve could see a deep gorge, cut far into the face of the precipice and leading steeply upward. He caught his breath. He had never imagined such a natural stairway. The incline was so precipitous that it seemed it would tax the most sure-footed horse. Boulders rested along the trail that led through it, as if hovering there temporarily, and the high walls on each side darkened the way, looming like a sinister threat.

“My gosh!” said he sincerely. Å“Do you have to go up that gulch every time you leave your cabin?”

“Yes—or else climb the slopes back of the plateau and make a wide circle, leaving the plateau to the north and coming down the southern ridges. We always go this way. I’m used to climbing it now.”

“Must have took a long time for the water to wash that out,” said Steve. “I’m new to this mountain country, but it looks to me like if somebody stubbed their toe on a rock, it would start a landslide that would bring the whole thing right down in that canyon.”

“I think of that, too,” she answered with a slight shudder. “I thank you for what you’ve done for me. But you mustn’t go any further. My uncle is always furious if anyone comes into these mountains.”

“What about Edwards?”

“I’ll tell my uncle and he’ll make him leave me alone.” She started to go, then hesitated.

“Listen,” said Steve, his heart beating wildly, “I’d like to know you better—will—will you meet me tomorrow somewhere?”

“Yes!” she spoke low and swiftly, then turned and ran lightly up the slope. Steve stood, looking after her, hat in hand.

Night had fallen as Steve Harmer rode back to the ranch of Hard Luck Harper.

“Clouds in the west and a-lookin’ like rain,

“And my blamed old slicker’s in the wagon again!”

he declaimed to the dark blue bowl of the star-flecked sky.

The crisp sharp scent of cedar was in the air and the wind fanned his cheek. He felt his soul grow and expand in the silence and the majesty of the night.

“Woke up one mornin’ on the Chisholm Trail—

“Rope in my hand and a cow by the tail!”

He drew rein at the cabin stoop and hailed his host hilariously. Old Hard Luck stood in the door and the starlight glinted on the steel in his hand.

“Huh,” grunted he suspiciously. “You done finally come back, ain’t you? I’d ’bout decided you done met up with Gila Murken and was layin’ in a draw somewheres with a thirty-thirty slug through yore innards. Come in and git yore hoofs under the table—I done cooked a couple of steers in hopes of stayin’ yore appetite a little.”

Steve tended to his horse and then entered the cabin, glancing at the long rifle which the old man had stood up against the cabin wall.

“That was a antique when they fought the Revolution,” said Steve. “What’s the idea? Are you afraid of Murken?”

“Afeard of Murken? That dub? I got no call to be afeard of him. And don’t go slingin’ mud at a gun that’s dropped more Indians than you ever see. That’s a Sharps .50 caliber and when I was younger I could shave a mosquito at two hundred yards with it.

“Naw, it ain’t Murken I’m studyin’. Listen!”

Again Steve caught the faint pulsing of the mountain drums.

“Every night they get louder,” said Hard Luck. Å“They say them redskins is plumb peaceful but you can’t tell me—the only peaceful Indian I ever see had at least two bullets through his skull. Them drums talks and whispers and they ain’t no white man knows what’s hatchin’ back up in them hills where nobody seldom ever goes. Indian magic! That’s what’s goin’ on, and red magic means red doin’s. I’ve fought ’em from Sonora to the Bad Lands and I know what I’m talkin’ about.”

“Your nerves is gettin’ all euchered up,” said Steve, diving into food set before him. Å“I kinda like to listen to them drums.”

“Maybe you’d like to hear ’em when they was dancin’ over yore scalp,” answered Hard Luck gloomily. Å“Thar’s a town about forty mile northwest of here whar them red devils comes to trade sometimes, ’steader goin’ to Rifle Pass, and a fellow come through today from thar and says they must be some strange goin’s on up in the Sunsets.

“ Å‘How come?’ says I.

“ Å‘Why,’ says he, Å‘them reservation Navajoes has been cartin’ down greenbacks to buy their tobaccer and calico and the other day the storekeepers done found the stuff is all counterfeit. They done stopped sellin’ to the Indians and sent for a Indian agent to come and investigate. Moreover,’ says he, Å‘somebody is sellin’ them redskins liquor too.’ ”

Hard Luck devoted his attention to eating for a few moments and then began again.

“How come them Indians gets any kind of money up in the mountains, much less counterfeit? Reckon they’re makin’ it theirselves? And who’s slippin’ them booze? One thing’s shore, Hell’s to pay when redskins git drunk and the first scalp they’ll likely take is the feller’s who sold them the booze.”

“Yeah?” returned Steve absent-mindedly. His thoughts were elsewhere.

“Did you find the mine?” asked Hard Luck sarcastically.

“What mine?” The Texan stared at his host blankly.

Hard Luck grunted scornfully and pushed back his chair. After awhile silence fell over the cabin, to be broken presently by Steve’s voice rising with dolorous enjoyment in the darkness:

“And he thought of his home, and his loved ones nigh,

“And the cowboys gathered to see him die!”

Hard Luck sat up in his bunk and cursed, and hurled a boot.

“For the love of mud, let a old man sleep, willya?”

As Steve drifted off into dreamland, his last thoughts were of gold, but it was not the lost ore of the Sunsets; it was the soft curly gold that framed the charming oval of a soft face. And still through the shimmery hazes of his dreams beat the sinister muttering of the Sunset drums.

The dew was still on the mountain grass when Steve rode up the long dim slopes to the glade where he had fought Edwards the day before. He sat down on a log and waited, doubting if she whom he sought would really come.

He sat motionless for nearly an hour, and then he heard a light sure step and she stood before him, framed in the young glow of the morning sun. The beauty of her took Steve’s breath and he could only stand, hat in hand, and gape, seeking feebly for words. She came straight to him, smiling, and held out her hand. The touch of her slim firm fingers reassured him and he found his voice.

“Miss Farrel, I plumb forgot yesterday to ask you where you’d rather meet me at, or what time. I come here because I figured you’d remember—I mean, you’d think—aw heck!” he stumbled.

“Yes, that was forgetful of us. I decided that you’d naturally come to the place where you found me yesterday and I came early because—because I was afraid you’d come and not find me here and think I wasn’t coming,” she finished rather confusedly.

As she spoke her eyes ran approvingly over Steve, noting his six-foot build of lithe manhood and the deep tan of his whimsical face.

Å“I promised to tell you all I know,” said she abruptly, twisting her fingers. She seemed paler and more worried than ever. Steve decided that she had reached the point where she was ready to turn to any man for help, stranger or not. Certainly some deep fear was preying on her.

Å“You know my name,” she said, seating herself on the log and motioning him to sit beside her. Å“Mr. Murken is my mother’s brother. My parents separated when I was very young and I’ve been living with an aunt in New York state. I’d never been west before, until my aunt died not long ago. Before she died she told me to go to her brother at Rifle Pass and not having anywhere else to go, I did so.

Å“I’d never seen my uncle and I found him very different from what I had expected. He didn’t live at Rifle Pass then, but had moved up in these mountains. I came on up here with a guide and my uncle seemed very much enraged because I had come. He let me stay but I’m very unhappy because I know he don’t want me. Yet, when I ask him to let me go, he refuses. He won’t even let me go to Rifle Pass unless he is with me, and he won’t let me go riding unless he’s with me. He says he’s afraid I’ll run away, yet I know he doesn’t love me or really want me here. He’s not exactly unkind to me, but he isn’t kind either.

Å“There are two men who stay up there most of the time: Edwards, the man you saw yesterday, and a large black-bearded man named Allison. That one, Allison, looks like a bandit or something, but he is very courteous to me. But Edwards—you saw what he did yesterday and he’s forever trying to make love to me when my uncle isn’t around. I’m afraid to tell my uncle about it, and I don’t know whether he’d do anything, if I did tell him.

“The other two men stay in a smaller cabin a little distance from the one occupied by my uncle and myself, and they won’t let me come anywhere near it. My uncle even threatened to whip me if I looked in the windows. I think they must have something hidden there. My uncle locks me in my cabin when they are all at work in the other cabin—whatever they’re doing in there.

Å“Sometimes some Indians come down the western slopes from somewhere away back in the hills, and sometimes my uncle rides away with them. Once a week one of the men loads his saddle bags full of something and rides away to be gone two or three days.

“I don’t understand it,” she added almost tearfully. “I can’t help but believe there’s something crooked about it. I’m afraid of Edwards and only a little less afraid of my uncle. I want to get away.”

Suddenly she seized his hands impulsively.

“You seem good and kind,” she exclaimed. Å“Won’t you help me? I’ll pay you—”

Å“You’ll what?” he said explosively.

She flushed.

“I beg your pardon. I should have known better than to make that remark. I know you’ll help me just from the goodness of your heart.”

Steve’s face burned crimson. He fumbled with his hat.

“Sure I’ll help you. If you want I’ll ride up and get your things—”

She stared at him in amazement.

“I don’t want you committing suicide on my account,” said she. “You’d get shot if you went within sight of my uncle. No, this is what I want you to do. I’ve told you my uncle won’t let me have a horse, and I certainly can’t walk out of these mountains. Can you meet me here early tomorrow morning with an extra horse?”

“Sure I can. But how are you goin’ to get your baggage away? Girls is usually got a lot of frills and things.”

“I haven’t. But anyway, I want to get out of this place if I have to leave my clothes, even, and ride out in a bathing suit. I’ll stroll out of the cabin in the morning, casually, come down the gulch and meet you here.”

Å“And then where will you want to go?”

“Any place is as good as the next,” she answered rather hopelessly. Å“I’ll have to find some town where I can make my own living. I guess I can teach school or work in an office.”

“I wish—” said he impulsively, and then stopped short.

“You wish what?” she asked curiously.

“That them drums would quit whoopin’ it up at night,” he added desperately, flushing as he realized how close he had been to proposing to a girl he had known only two days. He was surprised at himself; he had spoken on impulse and he wondered at the emotion which had prompted him.

She shivered slightly.

“They frighten me, sometimes. Every night they keep booming, and last night I was restless and every time I awoke I could hear them. They didn’t stop until dawn. This was the first time they’ve kept up all night.”

She rose.

Å“I’ve stayed as long as I dare. My uncle will get suspicious of me and come looking for me if I’m gone too long.”

Steve rose. Å“I’ll go with you as far as the gorge.”

Again Steve stood among the thick trees at the foot of the Ramparts and watched the girl go up the gorge, her slim form receding and growing smaller in his sight as she ascended. The gulch lay in everlasting shadow and Steve unconsciously held his breath, as if expecting those grim, towering walls to come crashing down on that slender figure.

Nearly at the upper mouth she turned and waved at him, and he waved back, then turned and made his way back to his horse. He rode carelessly, and with a slack rein, seeming to move in a land of rose-tinted clouds. His heart beat swiftly and his blood sang through his veins.

“I’m in love! I’m in love!” he warbled, wild-eyed, to the indifferent trees. Å“Oh heck! Oh golly! Oh gosh!”

Suddenly he stopped short. From somewhere further back and high above him came a quick rattle of rifle fire. As he listened another volley cracked out. A vague feeling of apprehension clutched at him. He glanced at the distant rim of the Ramparts. The sounds had seemed to come from that direction. A few straggling shots sounded faintly, then silence fell. What was going on up above those grim cliffs?

“Reckon I ought to go back and see?” he wondered. Å“Reckon if Murken and his bold boys is slaughterin’ each other? Or is it some wanderin’ traveler they’re greetin’? Aw, likely they’re after deer or maybe a mountain lion.”

He rode on slowly, but his conscience troubled him. Suddenly a familiar voice hailed him and from the trees in front of him a horseman rode.

“Hi yah!” The rider was Hard Luck Harper. He carried the long Sharps rifle across his saddle bow and his face was set in gloomy lines.

“I done got to worryin’ about a brainless maverick like you a-wanderin’ around these hills by yoreself with Gila Murken runnin’ wild thata-way, and I come to see if you was still in the land of the livin’!”

“And I reckon you’re plumb disappointed not to run into a murder or two.”

“I don’t know so much about them murders,” said the old man testily. “Didn’t I hear guns a-talkin’ up on the Ramparts a little while ago?”

“Likely you did, if you was listenin’.”

“Yeah—and people don’t go wastin’ ammunition fer nothin’ up here—look there!”

Hard Luck’s finger stabbed upward and Steve, a numbing sense of foreboding gripping his soul, whirled to look. Up over the tree-lined rim of the Ramparts drifted a thin spiral of smoke.

“My Lord, Hard Luck!” gasped Steve. “What’s goin’ on up there?”

“Shet up!” snarled the old man, raising his rifle. “I hear a horse runnin’ hard!”

The wild tattoo of hoofs crashed through the silence and a steed burst through the trees of the upper slope and came plunging down toward them, wild-eyed, nostrils flaring. On its back a crimsoned figure reeled and flopped grotesquely. Steve spurred in front of the frantic flying animal and caught the hanging rein, bringing the bronco to a rearing, plunging halt. The rider slumped forward and pitched to the earth.

“Edwards!” gasped Steve.

The man lay, staring up with blank wide eyes. Blood trickled from his lips and the front of his shirt was soaked in red. Hard Luck and Steve bent over him. At the first glance it was evident that he was dying.

“Edwards!” exclaimed Hard Luck. “What’s happened? Who shot you? And whar’s yore pards and the gal?”

“Dead!” Edwards’ unshaven lips writhed redly and his voice was a croak.

“Daid!” Hard Luck’s voice broke shrilly. “Who done it?íí

“Them Navajoes!” the voice sank to a ghastly whisper as blood rose to the pallid lips.

“I told you!” gibbered Hard Luck. “I knowed them drums meant deviltry! I knowed it!”

“Shut up, can’t you?” snarled Steve, torn by his emotions. He gripped the dying man’s shoulder with unconsciously brutal force and shook him desperately.

“Edwards,” he begged, “you’re goin’ over the ridge ñ can’t you tell us how it was before you go? Did you see Murken and his niece die?”

“Yes—it—was—like—this,” the man began laboriously. “I was—all set to go—to Rifle Pass—had my bronc loaded—Murken and Allison was out near—the corral—the gal was—in the cabin. All to once—the west slopes began to shower lead. Murken went down—at the first fire. Allison was hit—and I got a slug through me. Then a gang—of Navajoes come ridin’ down—the slopes—drunk and blood crazy.

Å“I got to my bronc—and started ridin’ and—they drilled me—a couple of times from behind. Lookin’ back I saw—Allison standin’ in the cabin door with—both guns goin’ and the gal—crouchin’ behind him. Then the whole mob—of red devils—rushed in and I saw—the knives flashin’ and drippin’ as—I come into—the gulch.”

Steve crouched, frozen and horror struck. It seemed that his heart had crumbled to ashes. The taste of dust was in his mouth.

Å“Any of ’em chasin’ you, Edwards?” asked Hard Luck. The old Indian fighter was in his element now; he had sloughed off his attitude of lazy good nature and his eyes were hard and cold as steel.

“Maybe—don’t know,” the wounded man muttered. Å“All our fault—Murken would give ’em whiskey. Warned him. They found out—the money—he was given’ ’em—was no good.”

The voice broke suddenly as a red tide gushed to Edwards’ lips. He lurched up on his elbows, then toppled back and lay still.

Hard Luck grunted. He stepped over to Edwards’ horse which stood trembling, and cut open the saddlebags. He nodded.

Å“No more’n I expected.”

Steve was rising slowly, mechanically wiping his hands on a wisp of grass. His face was white, his eyes staring.

“She’s dead!” he whispered. Å“She’s dead!”

Hard Luck, gazing at him, felt a pang in his heart. The scene brought back so poignantly the old bloody days of Indian warfare when men had seen their loved ones struck down by knife and arrow.

“Son,” said he, solemnly, Å“I never expected to see such a sight as this again.”

The Texan gave him a glance of agony, then his eyes blazed with a wild and terrible light.

Å“They killed her!” he screamed, beating his forehead with his clenched fists. Å“And by God, I’ll kill ’em all! I’ll kill—kill—”

His gun was swinging in his hand as he plunged toward his horse. Hard Luck sprang forward and caught him, holding him with a wiry strength that was astounding for his age. He ignored the savage protests and curses, dodged a blow of the gun barrel which the half-crazed Texan aimed at his face, and pinioned Steve’s arms. The youth’s frenzied passion went as suddenly as it had come, leaving him sobbing and shaken.

Å“Son,” said Hard Luck calmly, Å“cool down. I reckon you don’t want to lift them Navajo scalps any more’n I do, and before this game’s done, we’re goin’ to send more’n one of ’em over the ridge. But if you go gallopin’ up after ’em wide open thataway, you’ll never git the chance to even the score, fer they’ll drill you before you even see ’em. Listen to me, I’ve fought ’em from Sonora to the Bad Lands and I know what I’m talkin’ about. Git on yore bronc. We can’t do nothin’ more fer Edwards and we got work to do elsewhar. He said Allison and Murken and the gal was daid. I reckon Murken and Allison is gone over the ridge all right, but he didn’t rightly see ’em bump off the gal, and I’ll bet my hat she’s alive right now.”

Steve nodded shortly. He seemed to have aged years in the last few minutes. The easygoing young cowpuncher was gone, and in his place stood a cold steel fighting man of the old Texas blood. His hand was as steady as a rock, as he sheathed his pistol and swung into the saddle.

Å“I’m followin’ your lead, Hard Luck,” said he briefly. Å“All I ask is for you to get me within shootin’ and stabbin’ distance of them devils.”

The old man grinned wolfishly.

“Son, yore wants is simple and soon satisfied; follow me!”

Steve and Hard Luck rode slowly and warily up the tree-covered slopes which led to the foot of the Ramparts. Silence hung over the mountain forest like a deathly fog. Hard Luck’s keen old eyes roved incessantly, ferreting out the shadows, seeking for sign of something unnatural, something which was not as it should be, to betray the hidden assassins. He talked in a low, guarded tone. It was dangerous but he wished to divert Steve’s mind as much as possible.

Å“Steve, I done looked in Edwards’ saddle bags, and what you reckon I found? A whole stack of greenbacks, tens, twenties, fifties and hundreds, done up in bundles! It’s money he’s been packin’ out to Rifle Pass. Whar you reckon he got it?”

Steve did not reply nor did the old man expect an answer. The Texan’s eyes were riveted on the frowning buttresses of the Ramparts, which now loomed over them. As they came under the brow of the cliffs, the smoke they had seen further away was no longer visible.

“Reckon they didn’t chase Edwards none,” muttered Hard Luck. “Leastways they ain’t no sign of any horses followin’ his. There’s his tracks, alone. These Navajoes is naturally desert Indians, anyhow, and they’re ’bout as much outa place in the mountains as a white man from the plains. They can’t hold a candle to me, anyhow.”

They had halted in a thick clump of trees at the foot of the Ramparts and the mouth of the steep defile was visible in front of them.

Å“That’s a bad place,” muttered Hard Luck. Å“I been up that gulch before Gila built his cabins up on the plateau. Steve, we kin come at them Navajoes, supposin’ they’re still up on there, by two ways. We kin circle to the south, climb up the mountain-sides and come down the west slopes or we kin take a chance an’ ride right up the gulch. That’s a lot quicker, of course, pervidin’ we ain’t shot or mashed by fallin’ rocks afore we git to the top.”

Å“Let’s take it on the run,” urged Steve, quivering with impatience. Å“It’ll take more’n bullets and rocks to stop me now.”

“All right,” said Hard Luck, reining his horse out of the trees, Å“here goes!”

Of that wild ride up the gorge Steve never remembered very much. The memory was always like a nightmare, in which he saw dark walls flash past, heard the endless clatter of hoofs and the rattle of dislodged stones. Nothing seemed real except the pistol he clutched in his right hand and the laboring steed who plunged and reeled beneath him, driven headlong up the slope with spurs that raked the panting sides.

Then they burst into the open and saw the plateau spread wide and silent before them, with smoldering masses of coals where the cabins and corrals should have stood. They rode up slowly. The tracks of horses led away up into the hills to the west and there was no sign of life. Dreading what he might see, Steve looked. Down close to where the corral had been lay the body of Gila Murken. Lying partly in the coals that marked the remnants of the larger cabin, was the corpse of a large darkfaced man who had once worn a heavy beard, though now beard and hair were mostly scorched off. There was no sign of the girl.

Å“Do you—do you think she burned in the cabin, Hard Luck?”

Å“Naw, I know she didn’t fer the reason that if she hada, they’d be some charred bones. They done rode off with her.”

Steve felt a curious all-gone feeling, as if the realization that Joan was alive was too great a joy for the human brain to stand. Even though he knew that she must be in a fearful plight, at least she was living.

“Look it the stiffs,” said Hard Luck admiringly. Å“There’s whar Allison made his last stand—at the cabin door, protectin’ the gal, I reckon. This Allison seemed to be a mighty hard hombre but I reckon he had a streak of the man in him. Stranger in these parts to all but Murken.”

Four Navajoes lay face down in front of the white man’s body. They were clad only in dirty trousers and blankets flung about their shoulders. They were stone dead.

Å“Trail of blood from whar the corral was,” said Hard Luck. Å“They caught him in the open and shot him up afore he could git to the cabin, I figure. Down there at the corral Murken died. The way I read it, Allison made a break and got to the cabin whar the gal was. Then they surged in on him and he killed these four devils and went over the ridge hisself.”

Steve bent over the grim spectacle and then straightened.

“Thought I knowed him. Allison—Texas man he was. A real bad hombre down on the border. Got run outa El Paso for gun-runnin’ into Mexico.”

“He shore made a game stand fer his last fight.”

“Texas breed,” said Steve grimly.

“I reckon all the good battlers ain’t in Texas,” said Hard Luck testily. “Not denyin’ he put up a man-sized fight. Now then, look. Trails of fourteen horses goin’ west—five carryin’ weight, the rest bare—tell by the way the hoofs sink in, of course. All the horses missin’ out of the corral, four dead Indians here. That means they wan’t but a small party of ’em. Figurin’ one of the horses is bein’ rid by the gal, I guess we got only four redskins to deal with. Small war party scoutin’ in front of the tribe, I imagine, if the whole tribe’s on the war path. Now they’re lightin’ back into the hills with the gal, the broncs they took from the corral, and the horses of their dead tribesmen—which stopped Allison’s bullets. Best thing fer us to do is follow and try to catch up with ’em afore they git back to the rest of their gang.”

“Then, let’s go,” exclaimed Steve, trembling with impatience. “I’m nearly crazy standin’ here doin’ nothin’.”

Hard Luck glanced at the steeds, saw that they had recovered from the terrific strain of the flying climb, and nodded. As they rode past the embers of the smaller cabin, he drew rein for an instant.

“Steve, what’s them things?”

Steve looked sombrely at the charred and burnt machines which lay among the smoking ruins.

“Stamps and presses and steel dies,” said he. “Counterfeit machines. And look at the greenbacks.”

Fragments of green paper littered the earth as if they had been torn and flung about in anger or mockery.

“Murken and Edwards and Allison was counterfeiters, then. Huh! No wonder they didn’t want anybody snoopin’ around. That’s why Murken wouldn’t let the gal go—afeard she knew too much.”

They started on again at a brisk trot and Hard Luck ruminated.

“Mighta known it when they come up here a year ago. Reckon Edwards went to Rifle Pass every week, or some other nearby place, and put the false bills in circulation. Musta had an agent. And they give money to the Indians, too, to keep their mouths shet, and give ’em whiskey. And the Indians found they’d been given money which was no good. And bein’ all fired up with Murken’s bad whiskey, they just bust loose.”

“If so be we find Joan,” said Steve somberly, “say nothin’ about her uncle bein’ a crook.”

“Sure.”

Their steeds were mounting the western slopes, up which went the trail of the marauders. They crossed the ridge, went down the western incline and struck a short expanse of comparatively level country.

“Listen at the drums!” muttered Hard Luck. “Gettin’ nearer. The whole tribe must be on the march.”

The drums were talking loud and clear from somewhere in the vastness in front of them and Steve seemed to catch in their rumble an evil note of sinister triumph.

Then the two riders were electrified by a burst of wild and ferocious yells from the heavily timbered levels to the west, in the direction they were going. Flying hoofs beat out a thundering tattoo and a horse raced into sight running hard and low, with a slim white figure lying close along his neck. Behind came four hideous painted demons, spurring and yelling.

“Joan!” The word burst from Steve’s lips in a great shout and he spurred forward. Simultaneously he heard the crash of Hard Luck’s buffalo gun and saw the foremost redskin topple earthward, his steed sweeping past with an empty saddle. The girl whirled up beside him, her arms reaching for him.

“Steve!” Her cry was like the wail of a lost child.

“Ride for the plateau and make it down through the gulch!” he shouted, wheeling aside to let her pass. “Go!”

Then he swung back to meet the oncoming attackers. The surprize had been as much theirs as the white men’s. They had not expected to be followed so soon, and when they had burst through the trees, the sight of the two white men had momentarily stunned them with the unexpectedness of it. However, the remaining three came on with desperate courage and the white men closed in to meet them.

Hard Luck’s single shot rifle was empty, but he held it in his left hand, guiding his steed with his knees, while he drew a long knife with his free hand. Steve spurred in, silent and grim, holding his fire until the first of the attackers was almost breast to breast with him. Then, as the rifle stock in the red hands went up, Steve shot him twice through his painted face and saw the fierce eyes go blank before the body slumped from the saddle. At the same instant Hard Luck’s horse crashed against the bronc of another Indian and the lighter mustang reeled to the shock. The redskin’s thrusting blade glanced from the empty rifle barrel and the knife in Hard Luck’s right hand whipped in, just under the heart.

The lone survivor wheeled his mustang as if to flee, then pivoted back with an inhuman scream and fired point-blank into Steve’s face, so closely that the powder burned his cheek. Without stopping to marvel at the miracle by which the lead had missed, Steve gripped the rifle barrel and wrenched.

White man and Indian tumbled from the saddles, close-locked, and there, writhing and struggling in the dust, the Texan killed his man, beating out his brains with the pistol barrel.

“Hustle!” yelled Hard Luck. “The whole blame tribe is just over that rise not a half a mile away, if I’m to jedge by the sounds of them riding-drums!”

Steve mounted without a backward glance at the losers of that grim red game who lay so stark and motionless. Then he saw the girl, sitting her horse not a hundred yards away, and he cursed in fright. He and Hard Luck swept up beside her and he exclaimed:

“Joan, why didn’t you ride on, like I told you?”

“I couldn’t run away and leave you!” she sobbed; her face was deathly white, her eyes wide with horror.

“Hustle, blast it!” yelled Hard Luck, kicking her horse. “Git movin’! Do you love birds wanta git all our scalps lifted?”

Over the thundering of the flying hoofs, as they raced eastward, she cried:

“They were taking me somewhere—back to their tribe, maybe—but I worked my hands loose and dashed away on the horse I was riding. Oh, oh, the horrors I’ve seen today! I’ll die, I know I will.”

“Not so long as me and brainless here has a drop of blood to let out,” grunted Hard Luck, misunderstanding her.

They topped the crest which sloped down to the plateau and Joan averted her face.

“Good thing scalpin’s gone outa fashion with the Navajoes,” grunted Hard Luck under his breath, “or she’d see wuss than she’s already saw.”

They raced across the plateau and swung up to the upper mouth of the gulch. There Hard Luck halted.

“Take a little rest and let the horses git their wind. The Indians ain’t in sight yit and we kin see ’em clean across the plateau. With this start and our horses rested, we shore ought to make a clean gitaway. Now, Miss Joan, don’t you look at—at them cabins what’s burned. What’s done is done and can’t be undid. This game ain’t over by a long shot and what we want to do is to think how to save us what’s alive. Them that’s dead is past hurtin’.”

“But it is all so horrible,” she sobbed, drooping forward in her saddle. Steve drew up beside her and put a supporting arm about her slim waist. He was heart-torn with pity for her, and the realization that he loved her so deeply and so terribly.

“Shots!” she whimpered. “All at once—like an earthquake! The air seemed full of flying lead! I ran to the cabin door just as Allison came reeling up all bloody and terrible. He pushed me back in the cabin and stood in the door with a pistol in each hand. They came sweeping up like painted fiends, yelling and chanting.

“Allison gave a great laugh and shot one of them out of his saddle and roared: ‘Texas breed, curse you!’ And he stood up straight in the doorway with his long guns blazing until they had shot him through and through again and again, and he died on his feet.” She sobbed on Steve’s shoulder.

“Sho, Miss,” said Hard Luck huskily. “Don’t you worry none about Allison; I don’t reckon he woulda wanted to go out any other way. All any of us kin ask is to go out with our boots on and empty guns smokin’ in our hands.”

“Then they dragged me out and bound my wrists,” she continued listlessly, “and set me on a horse. They turned the mustangs out of the corral and then set the corral on fire and the cabins too, dancing and yelling like fiends. I don’t remember just what all did happen. It seems like a terrible dream.”

She passed a slim hand wearily across her eyes.

“I must have fainted, then. I came to myself and the horse I was on was being led through the forest together with the horses from the corral and the mustangs whose riders Allison had killed. Somehow I managed to work my hands loose, then I kicked the horse with my heels and he bolted back the way we had come.”

“Look sharp!” said Hard Luck suddenly, rising in his saddle. “There they come!”

The crest of the western slopes was fringed with war-bonnets. Across the plateau came the discordant rattle of the drums.

“Easy all!” said Hard Luck. “We got plenty start and we got to pick our way, goin’ down here. A stumble might start a regular avalanche. I’ve seen such things happen in the Sunsets. Easy all!”

They were riding down the boulder-strewn trail which led through the defile. It was hard to ride with a tight rein and at a slow gait with the noise of those red drums growing louder every moment, and the knowledge that the red killers were even now racing down the western slopes.

The going was hard and tricky. Sometimes the loose shale gave way under the hoofs, and sometimes the slope was so steep that the horses reared back on their haunches and slid and scrambled. Again Steve found time to wonder how Joan found courage to go up and down this gorge almost every day. Back on the plateau, now, he could hear the yells of the pursuers and the echoes shuddered eerily down the gorge. Joan was pale, but she handled her mount coolly.

“Nearly at the bottom,” said Hard Luck, after what seemed an age. “Risk a little sprint, now.”

The horses leaped out at the loosening of the reins and crashed out onto the slopes in a shower of flying shale and loose dirt. “Good business—” said Hard Luck—and then his horse stumbled and went to its knees, throwing him heavily.

Steve and the girl halted their mounts, sprang from the saddle. Hard Luck was up in an instant cursing.

“My horse is lame—go on and leave me!”

“No!” snarled Steve. “We can both ride on mine.”

He whirled to his steed; up on the plateau crashed an aimless volley as if fired into the air. Steve’s horse snorted and reared—the Texan’s clutching hand missed the rein and the bronco wheeled and galloped away into the forest. Steve stood aghast, frozen at this disaster.

“Go on!” yelled Hard Luck. “Blast you, git on with the gal and dust it outta here!”

Å“Get on your horse!” Steve whirled to the girl. Å“Get on and go!”

“I won’t!” she cried. Å“I won’t ride off and leave you two here to die! I’ll stay and die with you!”

“Oh, my Lord!” said Steve, cursing feminine stubbornness and lack of logic. Å“Grab her horse, Hard Luck. I’ll put her on by main force and—”

Å“Too late!” said Hard Luck with a bitter laugh. Å“There they come!”

Far up at the upper end of the defile a horseman was silhouetted against the sky like a bronze statue. A moment he sat his horse motionless and in that moment Hard Luck threw the old buffalo gun to his shoulder. At the reverberating crash the Indian flung his arms wildly and toppled headlong, to tumble down the gorge with a loose flinging of his limbs. Hard Luck laughed as a wolf snarls and the riderless horse was jostled aside by flying steeds as the upper mouth of the defile filled with wild riders.

Å“Git back to the trees,” yelled Hard Luck, leading the race from the cliff’s base, reloading as he ran. Å“Guess we kin make a last stand, anyway!”

Steve, sighting over his pistol barrel as he crouched over the girl, gasped as he saw the Navajoes come plunging down the long gulch. They were racing down-slope with such speed that their horses reeled to their knees again and again, recovering balance in a flying cloud of shale and sand. Rocks dislodged by the flashing hoofs rattled down in a rain. The whole gorge was crowded with racing horsemen. Then—

Å“I knowed it!” yelled Hard Luck, smiting his thigh with a clenched fist.

High up the gulch a horse had stumbled, hurtling against a great boulder. The concussion had jarred the huge rock loose from its precarious base and now it came rumbling down the slope, sweeping horses and men before it. It struck other boulders and tore them loose; the gorge was full of frantic plunging steeds whose riders sought vainly to escape the avalanche they had started. Horses went down screaming as only dying horses can scream, a wild babble of yells arose, and then the whole earth seemed to rock.

Jarred by the landslide, the overhanging walls reeled and shattered and came thundering down into the gorge, wiping out the insects which struggled there, blocking and closing the defile forever. Boulders and pieces of cliff weighing countless tons shelved off and came sliding down. The awed watchers among the trees rose silently, unspeaking. The air seemed full of flying stones, hurled out by the shattering fall of the great rocks. And one of these stones through some whim of chance came curving down through the trees and struck Hard Luck Harper just over the eye. He dropped like a log.

Steve, still feeling stunned, as if his brain had been numbed by the crash and the roar of the falling cliffs, knelt beside him. Hard Luck’s eyes flickered open and he sat up.

Å“Kids,” said he solemnly, Å“that was a terrible and awesome sight! I’ve seen a lot of hard things in my day and I ain’t no Indian lover, but it got me to see a whole tribe of fighting men git wiped out that way. But I knowed as shore as they started racing down that gulch, it’d happen.”

He glanced down idly at the stone which had struck him, started, stooped and took it up in his hand. Steve had turned to the girl, who, the reaction having set in, was sobbing weakly, her face hidden in her hands. The Texan put his arms about her hesitantly.

“Joan,” said he, Å“you ain’t never said nothin’ and I ain’t never said nothin’ but I reckon it hasn’t took words to show how I love you.”

“Steve—” broke in Hard Luck excitedly.

Å“Shut up!” roared Steve, glaring at him. “Can’t you see I’m busy?”

Hard Luck shrugged his shoulders and approached the great heap of broken stone and earth, from which loose shale was still spilling in a wide stream down the slight incline at the foot of the cliffs.

“Joan,” went Steve, Å“as I was sayin’ when that old buzzard interrupted, I love you, and—and—and if you feel just a little that way towards me, let me take care of you!”

For answer she stretched out her arms to him.

Å“Joan kid,” he murmured, drawing her cheek down on his bosom and stroking her hair with an awkward, gentle hand, Å“reckon I can’t offer you much. I’m just a wanderin’ cowhand—”

Å“You ain’t!” an arrogant voice broke in. Steve looked up to see Hard Luck standing over them. The old man held the stone which had knocked him down, while with the other hand he twirled his long drooping mustache. A strange air was evident about him—he seemed struggling to maintain an urbane and casual manner, yet he was apparently about to burst with pride and self-importance.

Å“You ain’t no wanderin’ cowboy,” he repeated. Å“You’ll never punch another cow as long as you live. Yore one fourth owner of the Sunset Lode Mine, the blamedest vein of ore ever discovered!”

The two stared at him.

“Gaze on this yer dornick!” said Hard Luck. Å“Note the sparkles in it and the general appearance which sets it plumb apart from the ordinary rock! And now look yonder!”

He pointed dramatically at a portion of the cliff face which had been uncovered by the slide.

“Quartz!” he exulted. Å“The widest, deepest quartz vein I ever see! Gold you can mighta near work out with yore fingers, by golly! I done figured it out—after I wandered away and got found by them buffalo hunters, a slide come and covered the lode up. That’s why I couldn’t never find it again. Now this slide comes along, forty year later, and uncovers it, slick as you please!

“Very just and proper, too. Indians euchered me outa my mine the first time and now Indians has give it back to me. I guess I cancel the debt of that lifted ha’r.

“Now listen to me and don’t talk back. One fourth of this mine belongs to me by right of discovery. One fourth goes to any relatives of Bill Hansen’s which might be living. For the other two fourths, I’m makin’ you two equal partners. How’s that?”

Steve silently gripped the old man’s hand, too full for speech. Hard Luck took the young Texan’s arm and laid it about Joan’s shoulders.

“Git to yore love makin’ and don’t interrupt a man what’s tryin’ to figure out how to spend a million!” said he loftily.

“Joan, girl,” said Steve softly, Å“what are you cryin’ about? It’s easy to forget horrors when you’re young. You’re wealthy now, we’re goin’ to be married just as soon as we can—and the drums of Sunset Mountains will never beat again.”

“I guess I’m just happy,” she answered, lifting her lips to his.

“He first come in the money, and he spent it just as free!

“He always drank good liquor wherever he might be!”

So sang Hard Luck Harper from the depths of his satisfaction.