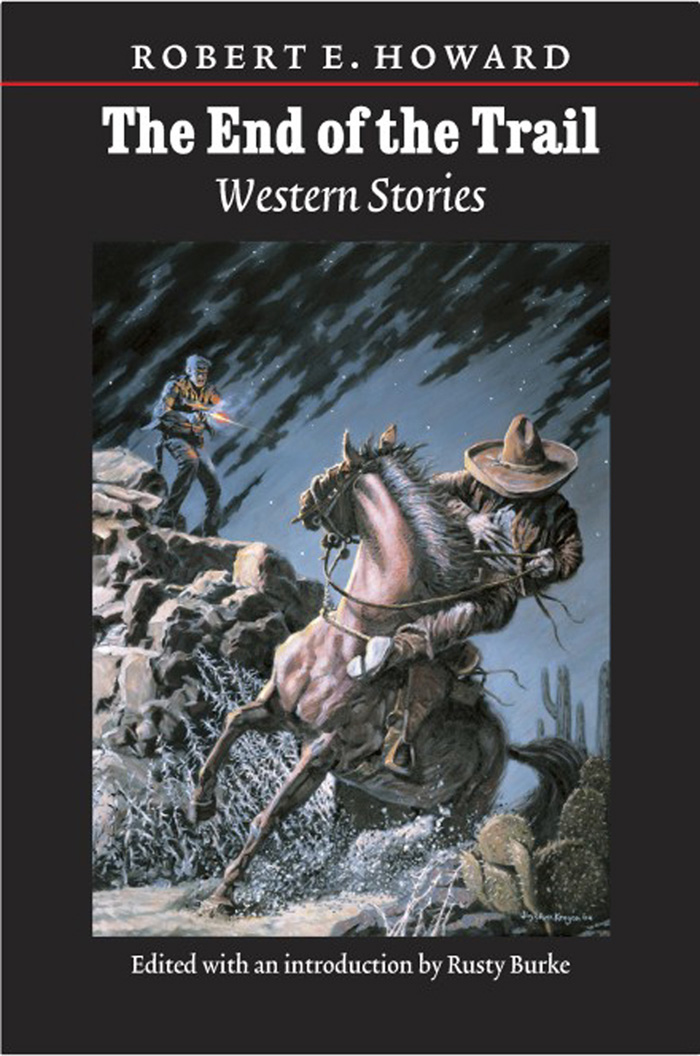

Cover from the collection The End of the Trail: Western Stories (2005).

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

Published in Cross Plains, #6 (1975),

though here taken from the 2005 collection The End of the Trail: Western Stories.

The Sonora Kid hated snakes with an obsessional hatred that embraced all species, venomous or harmless. Big Bill Harrigan was a practical joker whose sense of humor sometimes ran away with his judgment. Otherwise he would never have played the joke he did on the Sonora Kid in the Antelope Saloon. He could not have realized the full extent of the Kid’s fear and loathing for reptiles. At any rate, he approached the lean young cowpuncher, with a wink at the crowd, accosted him jovially—and tossed a chicken snake over his arm. The Kid, at the sight and touch of that wriggling horror, recoiled with a frantic yell that set the crowd off in a thunder of riotous mirth. And the Kid went temporarily crazy. White and blazing with unreasoning, instinctive mad fury, he drew and shot Big Bill Harrigan in the stomach. Big BillÅ’s roar of laughter broke short in a grunt of agony and he crashed to the floor.

The general mirth was cut off just as suddenly. The Kid, almost as stunned by his action as were the rest, was the first to recover himself. His other gun flashed from its scabbard, and both muzzles trained on the numbed crowd, as the killer backed to the door, face white and eyes blazing.

“Keep back!” he snarled. “Don’t move, none of you! Keep your hands up!”

“You can’t get away with this, Kid!” It was SheriÅff John MacFarlane, a tall, stalwart man, and utterly fearless. Å“It’s cold-blooded murder, and you know it! Harrigan ain’t even got a gun—”

“Shut up!” snarled the Kid. Å“Right or wrong, the noose ain’t wove for me, yet. Don’t none of you move, if you don’t wanta get your guts blown out!”

“I’ll get you!” raved MacFarlane. Å“I’ll follow you clean to Hell—”

With a snarl, the Kid bounded through the door, out of the square of light and into the darkness by the hitching-racks. So quickly he moved that he was in the saddle and wheeling his tall bay away, even as the first figures framed themselves in the doorway, baffled by the darkness, and wary of a shot from it. As the Kid whirled away, he crashed a volley into the earth among the hoofs of the horses at the rack, that sent them plunging and screaming and breaking loose in frantic terror.

Shots spat red in the dark behind him as he fled, and the night crackled with shouts and curses as the vengeful men sought to catch and quell frantic steeds. By the time the first pursuers were spurring on the trail of the fugitive, the drum of his horse’s hoofs had vanished in the night.

They did not catch the Sonora Kid that night, or the next, nor for the many days and nights that he kept the trail, putting much country between him and the memory and friends of Big Bill Harrigan. He knew John MacFarlane’s threat had been no idle one. The Sheriff had his own ideas of justice, and he had never failed to make good his promise to any man, law-breaker or not. The Kid knew MacFarlane would follow him; would follow him across state lines, even into Mexico, if necessary. And the Kid did not want to meet him. He was not afraid of MacFarlane; young as the Kid was, his name was mentioned with respect in that wild hill country southwest of the Pecos, from which he had come to MacFarlane’s country. But the Kid did not wish to kill the Sheriff; he knew MacFarlane was a good man. He knew his own action had seemed the act of a cold-blooded murderer. MacFarlane had never objected to a fair fight. But this, the Kid admitted, had been murder. Harrigan had been wearing no gun; he had stood empty-handed and laughing when the Kid’s .45 knocked him down. The Kid swore with sick regret and fury. He knew how he must appear in the sight of those who saw it. They could not understand that shock and fright of a fear that had haunted him since babyhood had made him momentarily loco. They would not—they could not—believe him if he said that he did not realize what he was doing when he shot jovial, good-natured Harrigan.

And because, rightly or wrongly, the Kid was human enough to desire not to decorate the end of a rope, he put days and nights of hard riding between him and the scene of the shooting.

It was not by chance that he rode into the camp of Black Jim Buckley, dusty and worn from sleeplessness and the grind of that long trek.

Buckley greeted him without any appearance of surprise.

“Glad to see you, Kid. I been wonderin’ how long it’d be before you started ridin’ outlaw trails. Man of your talents got no business herdin’ cows for a dollar a day. We can use you.”

Frank Reynolds and Dick Brill were with Buckley—veteran outlaws, gunfighters with an awesome list of dead, men hard and tough and dangerous as the mountain-land that bred them. They readily welcomed the Kid on Buckley’s say-so; there was no question of friendship or trust. They were a wolf-pack, banded together for mutual protection, wary of each other as of the rest of the world. These men were untamed, not amenable to the rules governing the mass of humanity. While they lived, they lived hard, violently, ruthlessly taking what they wished; when they died it would be in their boots, with their guns blazing, no more asking quarter than they had given it.

“I knew the Kid on the Pecos,” said Buckley easily. “Call him his regular name of Steve Allison back there. Never heard of him pullin’ no rustlin’ or stick-up jobs, but he was almighty quick with his shootin’ irons. You-all have heard of him.”

His companions nodded without changing expression. The Kid’s reputation was a dangerous thing to him, making it hard for him to live an ordinary life. Already famed as a gunfighter, with several killings behind him, the natural thing was for him to either turn law-enforcer or law-breaker. Circumstances had forced him into the latter course. It was impossible for a gunman to live the life of an ordinary cowhand.

“Got a job in mind down Río Juan way,” said Buckley. “Been kinda waitin’, hopin’ another good man would ride in. You couldn’t come at a better time.”

“Cattle or railroad?” demanded the Kid.

“Mine payroll. Hard for three men to work it. Need a man that ain’t known so well. You was made for the part. Look here—”

On the hard earth, with the point of his stockman’s knife, Buckley scratched a map, pointing out salient details as he unfolded his plan with a clarity and logic that showed why he was famed as the greatest of his profession. The three faces bent over his work, keen, alert, with almost wolf-like keenness that set them apart from other men. This keenness was no less apparent in the Kid’s features than in the grimmer, more hardened faces of his companions.

“Tomorrow we ride down to meet Shorty and get the rest of the details,” said Buckley. “You stay here and watch the cabin. Don’t want nobody to get a peek at you till we spring the trick. Anybody see you with us, it’d spoil the whole deal.”

After his companions had fallen asleep in their bunks, the Kid still sat silent and immobile before the dying fire, his chin propped on his bronzed fist. He seemed to glimpse the implacable hand of Fate driving him inexorably on to a life of crime. All his killings except the last had seemed necessary to him; at least they had been in fair fights. But because of them he had moved on continually, always restless and turbulent, yet always avoiding the actual state of outlawry by narrow margins. Now this latest twist of Fate had plunged him into it, and in a paroxysm of reasonless rage against the whims of Chance, he determined to play out the hand Life had dealt him to its red finish. If he were destined to ride the outlaw trail, then he would be no half-hearted weakling, but would carry himself in such a way that men would remember him longer for his crimes than they had remembered him for an honorable life. It was with a sort of bitter satisfaction that the Kid at last sought his bunk.

At dawn, Buckley and the others rode away, to their meeting with the mysterious Shorty—probably a treacherous employee of the mining company they intended looting. The Kid believed he knew why Buckley took both the others; the bandit chief was afraid to leave one of them alone with him. Reynolds and Brill were jealous of their lethal fame. The Kid was quick-tempered. Without the modifying presence of Buckley, a quarrel between Allison and either of the others was too likely a prospect to risk. Buckley wanted his full force for the job in hand. Afterwards—well, that was another matter. The Kid realized that sooner or later he would be drawn into a quarrel, to test his nerve, or because of some gunman’s quick-triggered vanity.

Alone, the time dragged slowly. The Kid’s restless nature abhorred idleness. His thoughts stung him. If he had any liquor he would have gotten blind drunk. He kept thinking of Big Bill Harrigan slumping to the floor. None of his other killings had ever worried him; but those men had died with their guns in their hands. Big Bill’s belt had been empty. The Kid swore sickly and resumed his panther-like pacing of the cabin.

Toward sundown he heard the noise of approaching hoofs. Quick suspicion flashed across his mind, as he recognized it as the sound of a single horse. He went quickly to the leather-hinged door and threw it open, just in time to see a tall horseman on a tired black stallion ride into the clearing. It was Sheriff John MacFarlane.

At the sight, all other emotions were swept from the Kid’s brain by a surge of red fury, the rage of a cornered thing.

“So you’ve hunted me down, you damned bloodhound!” he yelled.

“Wait, Kid—” shouted MacFarlane; then reading the unreasoning killerÅ’s lust in the Kid’s glaring eyes, he snatched at his gun. Even as it cleared the leather, the Kid’s .45 roared. MacFarlaneÅ’s hat flew from his head and he pitched from the saddle and lay still in an oozing pool of blood, and his horse reared and bolted.

The Kid came forward, cursing, his pistol smoking in his hand. He kicked the prostrate form in a paroxysm of resentment, then bent closer to examine his enemy. MacFarlane was still living. The Kid discovered that his bullet had ploughed through the Sheriff’s scalp, instead of going through the skull. He could not tell if the skull were fractured. He stood above the senseless man, an image of bewilderment.

If he had killed his enemy, the matter would have been at an end. But he could not put his gun to the senseless man’s head and finish him. The Kid did not reach this conclusion by an elaborate method of reasoning on morals and ethics. It was a part of him, just as his blinding speed with a gun was part of him. He could not murder in cold blood like that; nor could he leave the man there to die without attention.

At last, swearing heartily, he lifted the limp form and lugged it into the cabin. MacFarlane was taller and heavier than the wiry Kid, but the task was accomplished, and the Sheriff laid on a bunk in the back room of the cabin. The Kid set to work cleansing and dressing the wound, with skill acquired in many such tasks. MacFarlane began to show some signs of returning consciousness, and the bandaging was just completed when the Kid heard horses outside, and the sound of familiar voices. Recognizing them, he did not leave his work, and had just completed the bandages when Buckley stalked in, followed by his companions. They halted short at the sight of the man in the bunk.

“What the hell, Kid,” said Buckley softly. Å“What’s the deal?”

Å“Fellow followed me from the Antelope,” Allison answered briefly. “Said he would. Reckon he came alone. I creased him.”

“Reckon that’s middlin’ pore shootin’, Kid,” murmured Frank Reynolds.

The Kid took no notice of the remark. MacFarlane groaned and stirred, and Buckley leaned forward to peer into the wounded man’s face.

Å“Well, I’ll be damned,” he murmured. Å“This here’s a visitor I shore never expected to receive like this. Reckon you know who this is, Kid?”

Å“Reckon I do,” returned the other.

“Then why’n hell are you so polite with him?” demanded Brill. Å“If you know him, why didn’t you put another bullet in him and finish him?”

Icy lights flickered in the Kid’s steely gray eyes.

Å“Reckon that’s my business, Brill,” he returned slowly. No need to try to tell them that he couldn’t leave even a wounded enemy to die; needless as to tell the crowd in the Antelope that the touch of a fangless snake could drive a man momentarily loco.

“Drop it boys,” requested Buckley. “No use in wranglin’ amongst ourselves. The Kid done a good job when he dropped this coyote. Everybody makes a mistake now and then. I savvy how you feel, Kid. You ain’t been in the business long enough to realize that a fellow like this is just pizen to us, and don’t deserve mercy no more’n a copperhead snake. You reckon this Sheriff would tend to you and bandage you up after he shot you, les’n it was to save you for the gallows or the pen?”

Å“Don’t make no difference whether he would or not, Buckley,” the Kid answered. Å“That ain’t the point at all. If I’d killed him the first crack, itÅ’d been alright. But I wouldn’t let an egg-suckin’ hound lay and die without doin’ somethin’ for him.”

“That’s alright, Kid,” answered Buckley soothingly. Å“You don’t have to. You done what you felt was your duty. Now you just leave the rest to me. You don’t even have to watch, if you don’t wanta. Just go out and turn our hosses into the corral, and when you get back, everything’ll be o.k.”

The Kid scowled.

Å“What you mean, Buckley?”

Å“Why, hell!” broke in Dick Brill. Å“Are you so damned innocent, Kid? This here’s John MacFarlane; you think we’re goin’ to let him live?”

“You mean you’re goin’ to murder him?” ejaculated the Kid, aghast.

“That’s a hard way of puttin’ it, Kid,” protested Buckley. “We just aim to see that he don’t get in our way no more. I got my personal reasons, outside of the matter of ordinary safety precautions.”

“He’s comin’ to,” said Reynolds.

The Kid turned to see the Sheriff’s eyes flicker open. They were dazed. He muttered incoherently. The Kid bent and put a canteen of water to his lips. The wounded man drank mechanically.

“Kid,” said Buckley, Å“come out into the cabin and we’ll get all this straight.”

The Kid was the last to leave the back room. He closed the door after him.

Å“What you figgerin’ on doin’ with this rat, Kid?” asked Buckley.

“Why, tend to him till he’s dead or well,” answered Allison.

Brill swore beneath his breath. Buckley shook his head.

Å“Are you crazy, Kid? We got to dust outa here pronto. Everything’s set down at Río Juan. We won’t be ridin’ back this way.”

“Then you’ll ride without me,” the Kid answered doggedly.

“You mean you’ll throw us over, pass up the job?” Buckley’s voice was soft. “You mean you’ll let us down, for this bloodhound that’s been trailin’ you?”

“I mean I ain’t no murderer!” exclaimed the goaded Kid. Å“I can’t kill a man after I’ve knocked him out. I can’t leave him to die. I can’t let him be murdered. Any of them things would be just like blowin’ his brains out after I shot him down. I got no love for this hombre. But it ain’t a matter of like or dislike.”

“This fellow killed my brother,” Buckley’s voice was softer yet, but lights were beginning to glimmer in his eyes.

“And you can look him up and kill him after he gets on his feet. It ain’t nothin’ to me. But you ain’t massacrin’ him like a sheep.”

“Kid,” breathed Buckley Å“youÅ’ve showed your hand; now IÅ’m showin’ mine. You can’t let us down and get away with it. This coyote of the law donÅ’t leave this shack alive. Take it or leave it; if you leave it, you got to say your say with gun-smoke.”

There was an instant of tense silence, like a tick of Eternity in which Time seemed to stand still, and the night held its breath. In that brief space the Kid knew that he faced his supreme test. He saw the faces of his former companions, frozen into hard masks, in which their eyes burned with a wolfish light. Like a flicker of lightning, his hand snapped to his gun.

Buckley moved with equal speed. Their guns crashed together. The Kid reeled back against the wall, his six-shooter falling from his numb fingers. Buckley dropped, the whole top of his head torn off. On the heels of the double report came the thunder of the guns of Brill and Reynolds. Even as he reeled, the Kid’s left-hand gun was spurting smoke and flame. He rocked and jerked to the impact of lead, but he kept his feet. Reynolds was down, shot through the neck and belly. Brill, roaring like a bull and spouting blood, charged with a staggering rush, shooting as he came. He tripped over Buckley’s prostrate form, and as he fell, the Kid shot him straight through the heart.

The silence that followed the brief deadly thunder was appalling. The Kid lurched away from the wall. The cabin with its staring dead men and shreds of drifting smoke swam before his blurred sight. His whole right side seemed dead, and his left leg refused to balance his weight. Suddenly the floor seemed to rush up and strike him heavily. In the confused mist which engulfed him, he seemed to hear John MacFarlane calling to him, as if from a vast distance.

A little later he looked dizzily into MacFarlane’s face. The big sheriff was pale and his words seemed strange.

Å“Hang on, Kid; I ain’t much of a sawbones, but IÅ’m goin’ to do the best I can.”

Å“Lay off me, or I’ll blow your head off,” snarled the Kid groggily. Å“I ain’t askin’ no favors from you. I thought you was about dead.”

“Just knocked out,” answered MacFarlane. Å“I came to and heard everything that went on out here. My God, Kid, you’re shot to pieces—broken shoulder-bone, bullets in your thigh, breast, right arm—you realize you’ve just killed the three worst gunfighters in the State? And you done it for me. You got to get well, Kid—you got to.”

Å“So you can see me kick in a noose?” snarled the Kid. Å“Don’t you put no bandages on me. If I got to cash, I’ll cash like a gent. I wasnÅ’t born to be hanged.”

“You got it all wrong, Kid,” answered MacFarlane. Å“Get this straight—I wasn’t trailin’ you to arrest you. I was huntin’ you to put you right. The law ain’t lookin’ for you. Harrigan ain’t dead. He ain’t even hurt.”

The Kid laughed unpleasantly.

“No? Don’t lie, MacFarlane. I shot him plumb in the belly.”

“I know you did, but listen: Big Bill wasn’t wearin’ no gun-belt, you remember. Well, he had his six-shooter under his shirt, inside his waistband. Your bullet just flattened out against the cylinder of his gun. It knocked him down and took all the wind outa him and bruised his belly somethin’ fierce, but otherwise it didn’t hurt him none. He don’t hold no grudge. I got to thinkin’ about it, and decided you just didn’t think what you was doin’. Now I know it. Now get your mind to thinkin’ about gettin’ over these wounds.”

“I’ll do it, alright,” grunted the Kid, concealing his joy with the instinct of his breed. “Gotta redeem myself—I shoot Harrigan and I shoot you, and you both live to tell about it. Got to do somethin’ to persuade people I ain’t such a poor shot as all that.”

MacFarlane, knowing the Kid’s kind, laughed.