Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

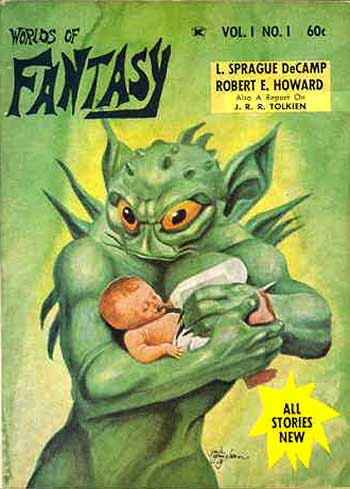

Published in Worlds of Fantasy #1, 1968.

“It’s no empire, I tell you! It’s only a sham. Empire? Pah! Pirates, that’s all we are!” It was Hunegais, of course, the ever moody and gloomy, with his braided black locks and drooping moustaches betraying his Slavonic blood. He sighed gustily, and the Falernian wine slopped over the rim of the jade goblet clenched in his brawny hand, to stain his purple, gilt-embroidered tunic. He drank noisily, after the manner of a horse, and returned with melancholy gusto to his original complaint.

“What have we done in Africa? Destroyed the big landholders and the priests, set ourselves up as landlords. Who works the land? Vandals? Not at all! The same men who worked it under the Romans. We’ve merely stepped into Roman shoes. We levy taxes and rents, and are forced to defend the land from the accursed Berbers. Our weakness is in our numbers. We can’t amalgamate with the people; we’d be absorbed. We can’t make allies and subjects out of them; all we can do is maintain a sort of military prestige—we are a small body of aliens sitting in castles and for the present enforcing our rule over a big native population who, it’s true, hate us no worse than they hated the Romans, but—”

“Some of that hate could be done away with,” interrupted Athaulf. He was younger than Hunegais, clean shaven, and not unhandsome, and his manners were less primitive. He was a Suevi, whose youth had been spent as a hostage in the East Roman court. “They are orthodox; if we could bring ourselves to renounce Arian—”

“No!” Hunegais’ heavy jaws came together with a snap that would have splintered lesser teeth than his. His dark eyes flamed with the fanaticism that was, among all the Teutons, the exclusive possession of his race. “Never! We are the masters! It is theirs to submit—not ours. We know the truth of Arian; if the miserable Africans can not realize their mistake, they must be made to see it—by torch and sword and rack, if necessary!” Then his eyes dulled again, and with another gusty sigh from the depths of his belly, he groped for the wine jug.

“In a hundred years the Vandal kingdom will be a memory,” he predicted. “All that holds it together now is the will of Genseric.” He pronounced it Geiserich.

The individual so named laughed, leaned back in his carven ebony chair and stretched out his muscular legs before him. Those were the legs of a horseman, but their owner had exchanged the saddle for the deck of a war galley. Within a generation he had turned a race of horsemen into a race of sea-rovers. He was the king of a race whose name had already become a term for destruction, and he was the possessor of the finest brain in the known world.

Born on the banks of the Danube and grown to manhood on that long trek westward, when the drifts of the nations crushed over the Roman palisades, he had brought to the crown forged for him in Spain all the wild wisdom the times could teach, in the feasting of swords and the surge and crush of races. His wild riders had swept the spears of the Roman rulers of Spain into oblivion. When the Visigoths and the Romans joined hands and began to look southward, it was the intrigues of Genseric which brought Attila’s scarred Huns swarming westward, tusking the flaming horizons with their myriad lances. Attila was dead, now, and none knew where lay his bones and his treasures, guarded by the ghosts of five hundred slaughtered slaves; his name thundered around the world, but in his day he had been but one of the pawns moved resistlessly by the hand of the Vandal king.

And when, after Chalons, the Gothic hosts moved southward through the Pyrenees, Genseric had not waited to be crushed by superior numbers. Men still cursed the name of Boniface, who called on Genseric to aid him against his rival, Aëtius, and opened the Vandal’s road to Africa. His reconciliation with Rome had been too late, vain as the courage with which he had sought to undo what he had done. Boniface died on a Vandal spear, and a new kingdom rose in the south. And now Aëtius, too, was dead, and the great war galleys of the Vandals were moving northward, the long oars dipping and flashing silver in the starlight, the great vessels heeling and rocking to the lift of the waves.

And in the cabin of the foremost galley, Genseric listened to the conversation of his captains, and smiled gently as he combed his unruly yellow beard with his muscular fingers. There was in his veins no trace of the Scythic blood which set his race somewhat aside from the other Teutons, from the long ago when scattered steppes-riders, drifting westward before the conquering Sarmatians, had come among the people dwelling on the upper reaches of the Elbe. Genseric was pure German; of medium height, with a magnificent sweep of shoulders and chest, and a massive corded neck, his frame promised as much of physical vitality as his wide blue eyes reflected mental vigor.

He was the strongest man in the known world, and he was a pirate—the first of the Teutonic sea-raiders whom men later called Vikings; but his domain of conquest was not the Baltic nor the blue North Sea, but the sunlit shores of the Mediterranean.

“And the will of Genseric,” he laughed, in reply to Hunegais’ last remark, “is that we drink and feast and let tomorrow take care of itself.”

“So you say!” snorted Hunegais, with the freedom that still existed among the barbarians. “When did you ever let a tomorrow take care of itself? You plot and plot, not for tomorrow alone, but for a thousand tomorrows to come! You need not masquerade with us! We are not Romans to be fooled into thinking you a fool—as Boniface was!”

“Aëtius was no fool,” muttered Thrasamund.

“But he’s dead, and we are sailing on Rome,” answered Hunegais, with the first sign of satisfaction he had yet evinced. “Alaric didn’t get all the loot, thank God! And I’m glad Attila lost his nerve at the last minute—the more plunder for us.”

“Attila remembered Chalons,” drawled Athaulf. “There is something about Rome that lives—by the saints, it is strange. Even when the empire seems most ruined—torn, befouled and tattered—some part of it springs into life again. Stilicho, Theodosius, Aëtius—who can tell? Tonight in Rome there may be a man sleeping who will overthrow us all.”

Hunegais snorted and hammered on the wine-stained board.

“Rome is as dead as the white mare I rode at the taking of Carthage! We have but to stretch our hands and grasp the plunder of her!”

“There was a great general once who thought as much,” said Thrasamund drowsily. “A Carthaginian, too, by God! I have forgotten his name. But he beat the Romans at every turn. Cut, slash, that was his way!”

“Well,” remarked Hunegais, “he must have lost at last, or he would have destroyed Rome.”

“That’s so!” ejaculated Thrasamund.

“We are not Carthaginians,” laughed Genseric. “And who said aught of plundering Rome? Are we not merely sailing to the imperial city in answer to the appeal of the Empress who is beset by jealous foes? And now, get out of here, all of you. I want to sleep.”

The cabin door slammed on the morose predictions of Hunegais, the witty retorts of Athaulf, the mumble of the others. Genseric rose and moved over to the table, to pour himself a last glass of wine. He walked with a limp; a Frankish spear had girded him in the leg long years ago.

He lifted the jeweled goblet to his lips—wheeled with a startled oath. He had not heard the cabin door open, but a man was standing across the table from him.

“By Odin!” Genseric’s Arianism was scarcely skin-deep. “What do you in my cabin?”

The voice was calm, almost placid, after the first startled oath. The king was too shrewd often to evince his real emotions. His hand stealthily closed on the hilt of his sword. A sudden and unexpected stroke—

But the stranger made no hostile movement. He was a stranger to Genseric, and the Vandal knew he was neither Teuton nor Roman. He was tall, dark, with a stately head, his dark flowing locks confined by a dark crimson band. A curling black patriarchal beard swept his breast. A dim, misplaced familiarity twitched at the Vandal’s mind as he looked.

“I have not come to harm you!” The voice was deep, strong and resonant. Genseric could tell little of his attire, since he was masked in a wide dark cloak. The Vandal wondered if he grasped a weapon under that cloak.

“Who are you, and how did you get into my cabin?” he demanded.

“Who I am, it matters not,” returned the other. “I have been on this ship since you sailed from Carthage. You sailed at night; I came aboard then.”

“I never saw you in Carthage,” muttered Genseric. “And you are a man who would stand out in a crowd.”

“I dwell in Carthage,” the stranger replied. “I have dwelt there for many years. I was born there, and all my fathers before me. Carthage is my life!” The last sentence was uttered in a voice so passionate and fierce that Genseric involuntarily stepped back, his eyes narrowing.

“The folk of the city have some cause of complaint against us,” said he, “but the looting and destruction was not by my orders; even then it was my intention to make Carthage my capital. If you suffered loss by the sack, why—”

“Not from your wolves,” grimly answered the other. “Sack of the city? I have seen such a sack as not even you, barbarian, have dreamed of! They called you barbaric. I have seen what civilized Romans can do.”

“Romans have not plundered Carthage in my memory,” muttered Genseric, frowning in some perplexity.

“Poetic justice!” cried the stranger, his hand emerging from his cloak to strike down on the table. Genseric noted the hand was muscular yet white, the hand of an aristocrat. “Roman greed and treachery destroyed Carthage; trade rebuilt her, in another guise. Now you, barbarian, sail from her harbors to humble her conqueror! Is it any wonder that old dreams silver the cords of your ships and creep amidst the holds, and that forgotten ghosts burst their immemorial tombs to glide upon your decks?”

“Who said anything of humbling Rome?” uneasily demanded Genseric. “I merely sail to arbitrate a dispute as to succession—”

“Pah!” Again the hand slammed down on the table. “If you knew what I know, you would sweep that accursed city clean of life before you turn your prows southward again. Even now those you sail to aid plot your ruin—and a traitor is on board your ship!”

“What do you mean?” Still there was neither excitement nor passion in the Vandal’s voice.

“Suppose I gave you proof that your most trusted companion and vassal plots your ruin with those to whose aid you lift your sails?”

“Give me that proof; then ask what you will,” answered Genseric with a touch of grimness.

“Take this in token of faith!” The stranger rang a coin on the table, and caught up a silken girdle which Genseric himself had carelessly thrown down.

“Follow me to the cabin of your counsellor and scribe, the handsomest man among the barbarians—”

“Athaulf?” In spite of himself Genseric started. “I trust him beyond all others.”

“Then you are not as wise as I deemed you,” grimly answered the other. “The traitor within is to be feared more than the foe without. It was not the legions of Rome which conquered me—it was the traitors within my gates. Not alone in swords and ships does Rome deal, but with the souls of men. I have come from a far land to save your empire and your life. In return I ask but one thing: drench Rome in blood!”

For an instant the stranger stood transfigured, mighty arm lifted, fist clenched, dark eyes flashing fire. An aura of terrific power emanated from him, awing even the wild Vandal. Then sweeping his purple cloak about him with a kingly gesture, the man stalked to the door and passed through it, despite Genseric’s exclamation and effort to detain him.

Swearing in bewilderment, the king limped to the door, opened it, and glared out on the deck. A lamp burned on the poop. A reek of unwashed bodies came up from the hold where the weary rowers toiled at their oars. The rhythmic clack vied with a dwindling chorus from the ships which followed in a long ghostly line. The moon struck silver from the waves, shone white on the deck. A single warrior stood on guard outside Genseric’s door, the moonlight sparkling on his crested golden helmet and Roman corselet. He lifted his javelin in salute.

“Where did he go?” demanded the king.

“Who, my lord?” inquired the warrior stupidly.

“The tall man, dolt,” exclaimed Genseric impatiently. “The man in the purple cloak who just left my cabin.”

“None has left your cabin since the lord Hunegais and the others went forth, my lord,” replied the Vandal in bewilderment.

“Liar!” Genseric’s sword was a ripple of silver in his hand as it slid from its sheath. The warrior paled and shrank back.

“As God is my witness, king,” he swore, “no such man have I seen this night.”

Genseric glared at him; the Vandal king was a judge of men and he knew this one was not lying. He felt a peculiar twitching of his scalp, and turning without a word, limped hurriedly to Athaulf’s cabin. There he hesitated, then threw open the door.

Athaulf lay sprawled across a table in an attitude which needed no second glance to classify. His face was purple, his glassy eyes distended, and his tongue lolled out blackly. About his neck, knotted in such a knot as seamen make, was Genseric’s silken girdle. Near one hand lay a quill, near the other ink and a piece of parchment. Catching it up, Genseric read laboriously.

“To her majesty the empress of Rome:

“I, thy faithful servant, have done thy bidding, and am prepared to persuade the barbarian I serve to delay his onset on the imperial city until the aid you expect from Byzantium has arrived. Then I will guide him into the bay I mentioned, where he can be caught as in a vise and destroyed with his whole fleet, and—”

The writing ceased with an erratic scrawl. Genseric glared down at him, and again the short hairs lifted on his scalp. There was no sign of the tall stranger, and the Vandal knew he would never be seen again.

“Rome shall pay for this,” he muttered; the mask he wore in public had fallen away; the Vandal’s face was that of a hungry wolf. In his glare, in the knotting of his mighty hand, it took no sage to read the doom of Rome. He suddenly remembered that he still clutched in his hand the coin the stranger had dropped on his table. He glanced at it, and his breath hissed between his teeth, as he recognized the characters of an old, forgotten language, the features of a man which he had often seen carved in ancient marble in old Carthage, preserved from Roman hate.

“Hannibal!” muttered Genseric.