Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

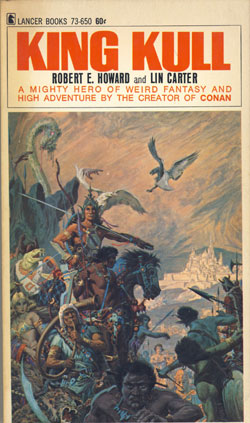

Published in King Kull, 1967.

King Kull went with Tu, chief councilor of the throne, to see the talking cat of Delcardes, for though a cat may look at a king, it is not given every king a look at a cat like Delcardes’. So Kull forgot the death threat of Thulsa Doom, the necromancer, and went to Delcardes.

Kull was skeptical, and Tu was wary and suspicious without knowing why, but years of counter-plot and intrigue had soured him. He swore testily that a talking cat was a fraud, a swindle, and a delusion; and maintained that should such a thing exist, it was a direct insult to the gods, who ordained that only man should enjoy the power of speech.

But Kull knew that in the old times beasts had talked to men, for he had heard the legends, handed down from his barbarian ancestors. So he was skeptical but open to conviction.

Delcardes helped the conviction. She lounged with supple ease upon her silk couch, like a great, beautiful feline, and looked at Kull from under long, drooping lashes, which lent unimaginable charm to her narrow, piquantly slanted eyes.

Her lips were full and red, and usually, as at present, curved in a faint enigmatical smile. Her silken garments and ornaments of gold and gems hid little of her glorious figure.

But Kull was not interested in women. He ruled Valusia, but for all that, he was an Atlantean and a savage in the eyes of his subjects. War and conquest held his attention, together with keeping his feet on the ever-rocking throne of the ancient empire, and the task of learning the customs and thoughts of the people he ruled.

To Kull, Delcardes was a mysterious and queenly figure, alluring, yet surrounded by a haze of ancient wisdom and womanly magic.

To Tu, she was a woman and therefore the latent base of intrigue and danger.

To Ka-nu, Pictish ambassador and Kull’s closest adviser, she was an eager child, parading under the effect of her play-acting; but Ka-nu was not there when Kull came to see the talking cat.

The cat lolled on a silken cushion on a couch of her own, and surveyed the king with inscrutable eyes. Her name was Saremes, and she had a slave who stood behind her, ready to do her bidding; a lanky man who kept the lower part of his face concealed by a thin veil which fell to his chest.

“King Kull,” said Delcardes, “I crave a boon of you before Saremes begins to speak, when I must be silent.”

“You may speak,” Kull answered.

The girl smiled eagerly and clasped her hands. “Let me marry Kulra Thoom of Zarfhaana.”

Tu broke in as Kull was about to speak. “My lord, this matter has been thrashed out at lengths before! I thought there was some purpose in requesting this visit! This—this girl has a strain of royal blood in her, and it is against the custom of Valusia that royal women should marry foreigners of lower rank.”

“But the king can rule otherwise,” pouted Delcardes.

“My lord,” said Tu, spreading his hands as one in the last stages of nervous irritation, “if she marries thus it is likely to cause war and rebellion and discord for the next hundred years.”

He was about to plunge into a dissertation on rank, genealogy, and history; but Kull interrupted, his short stock of patience exhausted. “Valka and Hotath! Am I an old woman or a priest to be bedevilled with such affairs? Settle it between yourselves and vex me no more with questions of mating! By Valka, in Atlantis men and women marry whom they please and none else.”

Delcardes pouted a little, made a face at Tu, who scowled back; then smiled sunnily and turned on her couch with a lissome movement. “Talk to Saremes, Kull; she will grow jealous of me.”

Kull eyed the cat uncertainly. Her fur was long, silky, and gray; her eyes slanting and mysterious.

“She looks very young, Kull; yet she is very old,” said Delcardes. “She is a cat of the Old Race who lived to be thousands of years old. Ask her age, Kull.”

“How many years have you seen, Saremes?” asked Kull idly.

“Valusia was young when I was old,” the cat answered in a clear though curiously timbred voice.

Kull started violently. “Valka and Hotath!” he swore. “She talks!”

Delcardes laughed softly in pure enjoyment, but the expression of the cat never altered.

“I talk, I think, I know, I am,” she said. “I have been the ally of queens and the councilor of kings ages before the white beaches of Atlantis knew your feet, Kull of Valusia. I saw the ancestors of the Valusians ride out of the far east to trample down the Old Race, and I was here when the Old Race came up out of the oceans so many eons ago that the mind of man reels when seeking to measure them. Older am I than Thulsa Doom, whom few men have ever seen. I have seen empires rise and kingdoms fall and kings ride in on their steeds and out on their shields. Aye, I have been a goddess in my time, and strange were the neophytes who bowed before me and terrible were the rites which were performed in my worship. For of old, beings exalted my land—beings as strange as their deeds.”

“Can you read the stars and foretell events?” Kull’s barbarian mind at once leaped to material ideas.

“Aye, the books of the past and the future are open to me, and I tell man what is good for him to know.”

“Then tell me,” said Kull, “where I misplaced the secret letter from Ka-nu yesterday.”

“You thrust it into the bottom of your dagger scabbard and then instantly forgot it,” the cat replied.

Kull started, snatched out his dagger, and shook the sheath. A thin strip of folded parchment tumbled out. “Valka and Hotath!” he swore. “Saremes, you are a witch of cats! Mark ye, Tu!”

But Tu’s lips were pressed in a straight, disapproving line, and he eyed Delcardes darkly. She returned his stare guilelessly, and he turned to Kull in irritation. “My lord, consider! This is all mummery of some sort.”

“Tu, none saw me hide that letter, for I myself had forgotten.”

“Lord king, any spy might—”

“Spy? Be not a greater fool than you were born, Tu. Shall a cat set spies to watch me hide letters?”

Tu sighed. As he grew older it was becoming increasingly difficult to refrain from showing exasperation toward kings. “My lord, give thought to the humans who may be behind the cat!”

“Lord Tu,” said Delcardes in a tone of gentle reproach, “you put me to shame, and you offend Saremes.”

Kull felt vaguely angered at Tu. “At least, Tu,” said he, “the cat talks; that you cannot deny.”

“There is some trickery,” Tu stubbornly maintained. “Man talks; beasts may not.”

“Not so,” said Kull, himself convinced of the reality of the talking cat, and anxious to prove that he was correct. “A lion talked to Kambra, and birds have spoken to the old men of the Sea-mountain tribe, telling them where game was hidden.

“None denies that beasts talk among themselves. Many a night have I lain on the slopes of the forest-covered hills or out on the grassy savannahs, and have heard the tigers roaring to one another across the star-light. Then why should some beast not learn the speech of man? There have been times when I could almost understand the roaring of the tigers. The tiger is my totem and is tabu to me, save in self-defense,” he added irrelevantly.

Tu squirmed. This talk of totem and tabu was good enough in a savage chief, but to hear such remarks from the king of Valusia irked him extremely. “My lord,” said he, “a cat is not a tiger.”

“Very true,” said Kull. “And this one is wiser than all tigers.”

“That is naught but truth,” said Saremes calmly. “Lord chancellor, would you believe then if I told you what was at this moment transpiring at the royal treasury?”

“No!” Tu snarled. “Clever spies may learn anything, as I have found.”

“No man can be convinced when he will not,” said Saremes imperturbably, quoting an ancient Valusian saying. “Yet know, lord Tu, that a surplus of twenty gold tals has been discovered, and a courier is even now hastening through the streets to tell you of it. Ah,” as a step sounded in the corridor without, “even now he comes.”

A slim courtier, clad in the gay garments of the royal treasury, entered, bowing deeply, and craved permission to speak. Kull having granted it, he said: “Mighty king and lord Tu, a surplus of twenty tals of gold has been found in the royal moneys.”

Delcardes laughed and clapped her hands delightedly, but Tu merely scowled. “When was this discovered?”

“A scant half-hour ago.”

“How many have been told of it?”

“None, my lord. Only I and the royal treasurer have known until just now when I told you, my lord.”

“Humph!” Tu waved him aside sourly. “Begone. I will see about this matter later.”

“Delcardes,” said Kull, “this cat is yours, is she not?”

“Lord king,” answered the girl, “no one owns Saremes. She only bestows on me the honor of her presence; she is a guest. She is her own mistress and has been for a thousand years.”

“I would that I might keep her in the palace,” said Kull.

“Saremes,” said Delcardes deferentially, “the king would have you as his guest.”

“I will go with the king of Valusia,” said the cat with dignity, “and remain in the royal palace until such time as it shall pleasure me to go elsewhere. For I am a great traveler, Kull, and it pleases me at times to go out over the world and walk the streets of cities where in ages gone by I have roamed forests, and to tread the sands of deserts where long ago I trod imperial streets.”

So Saremes, the talking cat, came to the royal palace of Valusia. Her slave accompanied her, and she was given a spacious chamber lined with fine couches and silken pillows. The best viands of the royal table were placed before her daily, and all the household of the king did homage to her except Tu, who grumbled to see a cat exalted, even a talking cat. Saremes treated him with amused contempt, but admitted Kull into a level of dignified equality.

She quite often came into his throne chamber, borne on a silken cushion by her slave, who must always accompany her, no matter where she went. At other times Kull came into her chamber, and they talked into the dim hours of dawn, and many were the tales she told him and ancient the wisdom that she imparted. Kull listened with interest and attention, for it was evident that this cat was wiser far than many of his councilors, and had gained more ancient wisdom than all of them together. Her words were pithy and oracular, but she refused to prophesy beyond minor affairs taking place in the everyday life of the palace or kingdom; save that she warned him against Thulsa Doom, who had sent a threat to Kull.

“For,” said she, “I, who have lived more years than you shall live minutes, know that man is better off without knowledge of things to come; for what is to be, will be, and man can neither avert nor hasten. It is better to go in the dark when the road must pass a lion and there is no other road.”

“Yes,” said Kull, “if what must be, is to be—a thing which I doubt—and a man be told what things shall come to pass and his arm weakened or strengthened thereby; then was that, too, foreordained?”

“If he was ordained to be told,” said Saremes, adding to Kull’s perplexity and doubt. “However, not all of life’s roads are set fast, for a man may do this or a man may do that, and not even the gods know the mind of a man.”

“Then,” said Kull dubiously, “all things are not destined if there be more than one road for a man to follow. And how can events then be prophesied truly?”

“Life has many roads, Kull,” answered Saremes. “I stand at the crossroads of the world, and I know what lies down each road. Still, not even the gods know what road a man will take, whether the right hand or the left hand, when he comes to the dividing of the ways; and once started upon a road, he cannot retrace his steps.”

“Then, in Valka’s name,” said Kull, “why not point out to me the perils or the advantages of each road as it comes and aid me in choosing?”

“Because there are bounds set upon the powers of such as I,” the cat replied, “lest we hinder the workings of the alchemy of the gods. We may not brush the veil entirely aside for human eyes, lest the gods take our power from us, and lest we do harm to man. For though there are many roads at each crossroads, still a man must take one of those and sometimes one is no better than another. So Hope flickers her lamp along one road and man follows, though that road may be the foulest of all.”

Then she continued, seeing Kull found it difficult to understand. “You see, lord king, that our powers must have limits, else we might grow too powerful and threaten the gods. So a mystic spell is laid upon us, and while we may open the books of the past, we may but grant flying glances of the future through the mist that veils it.”

Kull felt somehow that the argument of Saremes was rather flimsy and illogical, smacking of witchcraft and mummery; but with Saremes’ cold, oblique eyes gazing unwinkingly at him, he was not prone to offer any objections, even had he thought of any.

“Now,” said the cat, “I will draw aside the veil for an instant to your own good—let Delcardes marry Kulra Thoom.”

Kull rose with an impatient twitch of his mighty shoulders. “I will have naught to do with a woman’s mating. Let Tu attend to it.”

Yet Kull slept on the thought, and as Saremes wove the advice craftily into her philosophizing and moralizing in days to come, Kull weakened.

A strange sight it was indeed, to see Kull, his chin resting on his great fist, leaning forward and drinking in the distinct intonations of the cat Saremes as she lay curled on her silken cushion, or stretched languidly at full length; as she talked of mysterious and fascinating subjects, her eyes glinting strangely and her lips scarcely moving, if at all, while the slave Kuthulos stood behind her like a statue, motionless and speechless.

Kull highly valued her opinions, and he was prone to ask her advice—which she gave warily or not at all—on matters of state. Still, Kull found that what she advised usually coincided with his private wish, and he began to wonder if she were not a mind reader also.

Kuthulos irked him with his gauntness, his motionlessness, and his silence, but Saremes would have none other to attend her. Kull strove to pierce the veil that masked the man’s features, but though it seemed thin enough, he could tell nothing of the face beneath and out of courtesy to Saremes never asked Kuthulos to unveil.

Kull came to the chamber of Saremes one day, and she looked at him with enigmatical eyes. The masked slave stood statue-like behind her.

“Kull,” said she, “again I will tear the veil for you. Brule, the Pictish Spear-slayer, warrior of Ka-nu and your friend, has just been hauled beneath the surface of the Forbidden Lake by a grisly monster.”

Kull sprang up, cursing in rage and alarm. “Ha! Brule? Valka’s name, what was he doing about the Forbidden Lake?”

“He was swimming there. Hasten, you may yet save him, even though he be borne to the Enchanted Land which lies below the Lake.”

Kull whirled toward the door. He was startled, but not so much as he would have been had the swimmer been someone else, for he knew the reckless irreverence of the Pict, chief among Valusia’s most powerful allies.

He started to shout for guards, when Saremes’ voice stayed him.

“Nay, my lord. You had best go alone. Not even your command might make men accompany you into the waters of that grim lake, and by the custom of Valusia, it is death for any man to enter there save the king.”

“Aye, I will go alone,” said Kull, “and thus save Brule from the anger of the people, should he chance to escape the monsters. Inform Ka-nu.”

Kull, discouraging respectful inquiries with wordless snarls, mounted his great stallion and rode out of Valusia at full speed. He rode alone and he ordered that none follow him. That which he had to do, he could do alone, and he did not wish anyone to see when he brought Brule or Brule’s corpse out of the Forbidden Lake. He cursed the reckless inconsideration of the Pict, and he cursed the tabu which hung over the lake; the violation of which might cause rebellion among the Valusians.

Twilight was stealing down from the mountains of Zalgara when Kull halted his horse on the shores of the lake, which lay amid a great lonely forest. There was certainly nothing forbidding in its appearance, for its waters spread blue and placid from beach to wide white beach, and the tiny islands rising about its bosom seemed like gems of emerald and jade. A faint shimmering mist rose from it, enhancing the air of lazy unreality which lay about the regions of the lake. Kull listened intently for a moment, and it seemed to him as though faint and faraway music breathed up through the sapphire waters.

He cursed impatiently, wondering if he were beginning to be bewitched, and flung aside all garments and ornaments except his girdle, loin-clout, and sword. He waded out into the shimmery blueness until it lapped his thighs; then, knowing that the depth swiftly increased, he drew a deep breath and dived.

As he swam down through the sapphire glimmer, he had time to reflect that this was probably a fool’s errand. He might have taken time to find from Saremes just where Brule had been swimming when attacked and whether he was destined to rescue the warrior or not. Still, he thought that the cat might not have told him, and even if she had assured him of failure, he would have attempted what he was now doing, anyway. So there was truth in Saremes’ saying that men were better untold about the future. As for the location of the site where Brule had been attacked, the monster might have dragged him anywhere. Kull intended to explore the lake bed until—

Even as he ruminated thus, a shadow flashed by him, a vague shimmer in the jade and sapphire shimmer of the lake. He was aware that other shadows swept by him on all sides, but he could not make out their forms.

Far beneath him he began to see the glimmer ot the lake bottom which seemed to glow with a strange radiance. Now the shadows were all about him; they wove a serpentine net about him, an ever-changing thousand-hued glittering web of color. The water here burned topaz and the things wavered and scintillated in its faery splendor. Like the shades and shadows of colors they were, vague and unreal, yet opaque and gleaming.

However, Kull, deciding that they had no intention of attacking him, gave them no more attention, but directed his gaze on the lake floor which his feet just then lightly struck. He started, and could have sworn that he had landed on a living creature, for he felt a rhythmic movement beneath his bare feet. The faint glow was evident there at the bottom of the lake; as far as he could see, stretching away on all sides until it faded into the lambent sapphire shadows, the lake floor was one solid level of fire that faded and glowed with unceasing regularity. Kull bent closer; the floor was covered by a sort of short moss-like substance which shone like white flame. It was as if the lake bed were covered with myriads of fireflies which raised and lowered their wings together. And this moss throbbed beneath his feet like a living thing.

Now Kull began to swim upward again. Raised among the sea-mountains of ocean-girt Atlantis, he was like a sea creature himself. As much at home in the water as any Lemurian, he could remain under the surface twice as long as the ordinary swimmer, but this lake was deep and he wished to conserve his strength.

He came to the top, filled his enormous chest with air, and dived again. Again the shadows swept about him, almost dazzling his eyes with their ghostly gleams. He swam faster this time, and having reached the bottom, he began to walk along it as fast as the clinging substance about his limbs would allow; the while the fire-moss breathed and glowed and the color things flashed about him and monstrous, nightmarish shadows fell across his shoulder upon the burning floor, flung by unseen beings.

The moss was littered by the skulls and the bones of men who had dared the Forbidden Lake. Suddenly, with a silent swirl of the waters, a thing rushed upon Kull. At first the king thought it to be a huge octopus, for the body was that of an octopus, with long waving tentacles; but as it charged upon him he saw that it had legs like a man and a hideous semi-human face leered at him from among the writhing, snaky arms of the monster.

Kull braced his feet, and as he felt the cruel tentacles whip about his limbs, he thrust his sword with cool accuracy into the midst of that demoniac face, and the creature lumbered down and died at his feet with grisly, soundless gibbering. Blood spread like a mist about him, and Kull thrust strongly against the floor with his legs and shot upward.

He burst into the fast-fading light, and even as he did, a great form came skimming across the water toward him—a water spider, but this one was larger than a boar, and its cold eyes gleamed hellishly. Kull, keeping himself afloat with his feet and one hand, raised his sword, and as the spider rushed in, he cleft it halfway through the body; and it sank silently.

A slight noise made him turn, and another, larger than the first, was almost upon him. This one flung over the king’s arms and shoulders strands of clinging web that would have meant doom for any but a giant. But Kull burst the grim shackles as if they had been strings, and, seizing a leg of the thing as it towered above him, he thrust the monster through again and again till it weakened in his grasp and floated away, reddening the waters.

“Valka!” muttered the king, “I am not like to go without employment here. Yet these things be easy to slay. How could they have overcome Brule, who is second only to me in battle might in all the Seven Kingdoms?”

But Kull was to find that grimmer spectres than these haunted the death-ridden abysses of Forbidden Lake. Again he dived and this time only the color-shadows and the bones of forgotten men met his glance. Again he rose for air and for the fourth time he dived.

He was not far from one of the islands, and as he swam downward, he wondered what strange things were hidden by the dense emerald foliage which cloaked these islands. Legend said that temples and shrines reared there that were never built by human hands, and that on certain nights the lake beings came out of the deeps to enact eerie rites there.

The rush came just as his feet struck the moss. It came from behind, and Kull, warned by some primal instinct, whirled just in time to see a great form loom over him—a form neither man nor beast, but horribly compounded of both—to feel gigantic fingers close on arm and shoulder.

He struggled savagely, but the thing held his sword arm helpless, and its talons sank deeply into his left forearm. With a volcanic wrench he twisted about so that he could at least see his attacker. The thing was something like a monstrous shark, but a long, cruel horn, curved like a saber, jutted up from its snout. It had four arms, human in shape but inhuman in size and strength and in the crooked talons of the fingers. With two arms the monster held Kull helpless, and with the other two it bent his head back to break his spine. But not even such a grim being as this might so easily conquer Kull of Atlantis. A wild rage surged up in him, and the king of Valusia went berserk.

Bracing his feet against the yielding moss, he tore his left arm free with a heave and wrench of his shoulders. With cat-like speed, he sought to shift the sword from right hand to left and, failing in this, struck savagely at the monster with clenched fist. But the mocking sapphirean stuff about him foiled him, breaking the force of his blow. The shark-man lowered his snout, but, before he could strike upward, Kull gripped the horn with his left hand and held fast.

Then followed a test of might and endurance. Kull, unable to move with any speed in the water, knew his only hope was to keep in close and wrestle with his foe in such manner as to counterbalance the monster’s quickness. He strove desperately to tear his sword arm loose, and the shark-man was forced to grasp it with all four of his hands. Kull gripped the horn and dared not let go lest he be disemboweled with its terrible upward thrust, and the shark-man dared not release with a single hand the arm that held Kull’s long sword.

So they wrenched and wrestled, and Kull saw that he was doomed if it went on in this manner. Already he was beginning to suffer for want of air. The gleam in the cold eyes of the shark-man told that he, too, recognized the fact that he had but to hold Kull below the surface until he drowned.

A desperate plight indeed, for any man. But Kull of Atlantis was no ordinary man. Trained from childhood in a hard and bloody school, with steel muscles and dauntless brain bound together by the coordination that makes the super-fighter, he added to this a courage which never faltered and a tigerish rage which on occasion swept him up to superhuman deeds.

So now, conscious of his swiftly approaching doom and goaded to frenzy by his helplessness, he decided upon action as desperate as his need. He released the monster’s horn, at the same time bending his body as far back as he could and gripping the nearest arm of the thing with the free hand.

Instantly the shark-man struck, his horn ploughing along Kull’s thigh and then—the luck of Atlantis!—wedging fast in Kull’s heavy girdle. And as he tore it free, Kull sent his mighty strength through the fingers that held the monster’s arm, and crushed clammy flesh and inhuman bone like rotten fruit between them.

The shark-man’s mouth gaped silently with the torment and he struck again wildly. Kull avoided the blow, and losing their balance, they went down together, half buoyed by the jade surge in which they wallowed. And as they tossed there, Kull tore his sword arm from the weakening grip and, striking upward, split the monster open.

The entire battle had consumed only a very brief time, but to Kull, as he swam upward, his head singing and a great weight seeming to press his ribs, it seemed like hours. He saw dimly that the lake floor shelved suddenly upward close at hand and knew that it sloped to an island; then the water came alive about him and he felt himself lapped from shoulder to heel in gigantic coils which even his steel muscles could not break. His consciousness was fading—he felt himself borne along at terrific speed—there was a sound of many bells—then suddenly he was above water and his tortured lungs were drinking in great draughts of air. He was whirling along through utter darkness, and he had time to take only a long breath before he was again swept under.

Again light glowed about him, and he saw the fire-moss throbbing far below. He was in the grasp of a great serpent who had flung a few lengths of its sinuous body about him like huge cables and was now bearing him to what destination Valka alone knew.

Kull did not struggle, reserving his strength. If the snake did not keep him so long under water that he died, there would no doubt be a chance of battle in the creature’s lair or wherever he was being taken.

As it was, Kull’s limbs were pinioned so close that he could no more free an arm than he could have flown. The serpent, racing through the blue deeps so swiftly, was the largest Kull had ever seen—a good two hundred feet of jade and golden scales, vividly and wonderfully colored. Its eyes, when they turned toward Kull, were like icy fire, if such a thing can be. Even then Kull’s imaginative soul was struck with the bizarreness of the scene: that great green and gold form flying through the burning topaz of the lake, while the shadow-colors weaved dazzlingly about it.

The fire-gemmed floor sloped upward again—either for an island or the lake shore—and a great cavern suddenly appeared before them. The snake glided into this, the fire-moss ceased, and Kull found himself partly above the surface in unlighted darkness. He was borne along in this manner for what seemed like a very long time; then the monster dived again.

Again they came up into light, but such light as Kull had never before seen. A luminous glow shimmered duskily over the face of the waters which lay dark and still. And Kull knew that be was in the Enchanted Domain under the bottom of Forbidden Lake, for this was no earthly radiance; it was a black light, blacker than any darkness; yet it lit the unholy waters so that he could see the dusky glimmer of them and his own dark reflection in them. The coils suddenly loosed from his limbs, and he struck out for a vast bulk that loomed in the shadows in front of him.

Swimming strongly, he approached and saw that it was a great city. On a great level of black stone, it towered up and up until its sombre spires were lost in the blackness above the unhallowed light, which, black also, was yet of a different hue. Huge square-built massive buildings of mighty basaltic-like blocks fronted him as he clambered out of the clammy waters and strode up the steps which were cut into the stone like steps in a wharf. Columns rose gigantically between the buildings.

No gleam of earthly light lessened the grimness of this inhuman city, but from its walls and towers the black light flowed out over the waters in vast throbbing waves.

Kull was aware that in a wide space before him, where the buildings swept away on each side, a huge concourse of beings confronted him. He blinked, striving to accustom his eyes to the strange illumination.

The beings came closer, and a whisper ran among them like the waving of grass in the night wind. They were light and shadowy, glimmering against the blackness of their city, and their eyes were eery and luminous.

Then the king saw that one of their number stood in front of the rest. This one was much like a man, and his bearded face was high and noble, but a frown hovered over his magnificent brows.

“You come like a herald of all your race,” said this lake-man suddenly. “Bloody and bearing a red sword.”

Kull laughed angrily, for this smacked of injustice.

“Valka and Hotath!” said the king. “Most of this blood is mine own and was let by things of your cursed lake.”

“Death and ruin follow the course of your race,” said the lake-man sombrely. “Do we not know? Aye, we reigned in the lake of blue waters before mankind was even a dream of the gods.”

“None molests you—” began Kull.

“They fear to. In the old days men of the earth sought to invade our dark kingdom. And we slew them, and there was war between the sons of man and the people of the lakes. And we came forth and spread terror among the earthlings, for we knew that they bore only death for us and that they yielded only to slaying. And we wove spells and charms and burst their brains and shattered their souls with our magic so they begged for peace, and it was so. The men of earth laid a tabu on this lake so that no man may come here save the king of Valusia. That was thousands of years ago. No man has ever come into the Enchanted Land and gone forth, save as a corpse floating up through the still waters of the upper lake. King of Valusia, or whoever you be, you are doomed.”

Kull snarled in defiance. “I sought not your cursed kingdom. I seek Brule the Spear-slayer whom you dragged down.”

“You lie,” the lake-man answered. “No man has dared this lake for over a hundred years. You come seeking treasure or to ravish and slay like all your bloody-handed kind. You die!”

And Kull felt the whisperings of magic charms about him; they filled the air and took physical form, floating in the shimmering light like wispy spider-webs, clutching at him with vague tentacles. But Kull swore impatiently and swept them aside and out of existence with his bare hand. For against the fierce elemental logic of the savage, the magic of decadency had no force.

“You are young and strong,” said the lake-king. “The rot of civilization has not yet entered your soul and our charms may not harm you, because you do not understand them. Then we must try other things.”

And the lake-beings about him drew daggers and moved upon Kull. Then the king laughed and set his back against a column, gripping his sword hilt until the muscles stood out on his right arm in great ridges.

“This is a game I understand, ghosts,” he laughed.

They halted.

“Seek not to evade your doom,” said the king of the lake, “for we are immortal and may not be slain by mortal arms.”

“You lie, now,” answered Kull, with the craft of the barbarian, “for by your own words you feared the death my kind brought among you. You may live forever, but steel can slay you. Take thought among yourselves. You are soft and weak and unskilled in arms; you bear your blades unfamiliarly. I was born and bred to slaying. You will slay me, for there are thousands of you and I but one; yet your charms have failed, and many of you shall die before I fall. I will slaughter you by the scores. Take thought, men of the lake; is my slaying worth the lives it will cost you?”

For Kull knew that beings who slay by steel may be slain by steel, and he was unafraid. A figure of threat and doom, bloody and terrible he loomed above them.

“Aye, consider,” he repeated, “is it better that you should bring Brule to me and let us go, or that my corpse shall lie amid sword-torn heaps of your dead when the battle shout is silent? Nay, there be Picts and Lemurians among my mercenaries who will follow my trail even into the Forbidden Lake and will drench the Enchanted Land with your gore if I die here. For they have their own tabus, and they reck not of the tabus of the civilized races; nor care they what may happen to Valusia, but think only of me who am of barbarian blood like themselves.”

“The old world reels down the road to ruin and forgetfulness,” brooded the lake-king. “And we that were all-powerful in bygone days must brook to be bearded in our own kingdom by an arrogant savage. Swear that you will never set foot in Forbidden Lake again and that you will never let the tabus be broken by others, and you shall go free.”

“First bring the Spear-slayer to me.”

“No such man has ever come to this lake.”

“Nay? The cat Saremes told me—”

“Saremes? Aye, we knew her of old when she came swimming down through the green waters and abode for some centuries in the courts of the Enchanted Land; the wisdom of the ages is hers, but I knew not that she spoke the speech of earthly men. Still, there is no such man here, and I swear—”

“Swear not by gods or devils,” Kull broke in. “Give your word as a true man.”

“I give it,” said the lake-king, and Kull believed, for there was a majestic bearing about the king which made Kull feel strangely small and rude.

“And I,” said Kull, “give you my word—which has never been broken—that no man shall break the tabu or molest you in any way again.”

“And I believe you, for you are different from any earthly man I ever knew. You are a real king and, what is greater, a true man.”

Kull thanked him and sheathed his sword, turning toward the steps.

“Know ye how to gain the outer world, king of Valusia?”

“As to that,” answered Kull, “if I swim long enough I suppose I shall find the way. I know that the serpent brought me clear through at least one island and possibly many, and that we swam in a cave for a long time.”

“You are bold,” said the lake-king, “but you might swim forever in the dark.”

He raised his hands, and a behemoth swam to the foot of the steps.

“A grim steed,” said the lake-king, “but he will bear you safely to the very shore of the upper lake.”

“A moment,” said Kull. “Am I at present beneath an island, or the mainland—or is this land in truth beneath the lake floor?”

“You are at the centre of the universe as you are always. Time, place, and space are illusions, having no existence save in the mind of man which must set limits and bounds in order to understand. There is only the underlying reality, of which all appearances are but outward manifestations, just as the upper lake is fed by the waters of this real one. Go now, king, for you are a true man even though you be the first wave of the rising tide of savagery which shall overwhelm the world ere it recedes.”

Kull listened respectfully, understanding little but realizing that this was high magic. He struck hands with the lake-king, shuddering a little at the feel of that which was flesh, but not human flesh; then he looked once more at the great black buildings rearing silently and the murmuring moth-like forms among them, and he looked out over the shiny jet surface of the waters with the waves of black light crawling like spiders across it. And he turned and went down the stair of the water’s edge and sprang on the back of the behemoth.

Eons followed, of dark caves and rushing waters and the whisper of gigantic unseen monsters; sometimes above and sometimes below the surface the behemoth bore the king, and finally the fire-moss leaped up and they swept up through the blue of the burning water; and Kull waded to land.

Kull’s stallion stood patiently where the king had left him. The moon was just rising over the lake, whereat Kull swore amazedly.

“A scant hour ago, by Valka, I dismounted here! I had thought that many hours and possibly days had passed since then.”

He mounted and rode toward the city of Valusia, reflecting that there might have been some meaning in the lake-king’s remarks about the illusion of time.

Kull was weary, angry, and bewildered. The journey through the lake had cleansed him of the blood, but the motion of riding started the gash in his thigh to bleeding again; moreover, the leg was stiff and irked him somewhat. Still, the main thought that presented itself was that Saremes had lied to him, either through ignorance or through malicious forethought, and had come near to sending him to his death. For what reason?

Kull cursed, reflecting what Tu would say. Still, even a talking cat might be innocently wrong, but hereafter Kull determined to lay no weight to the words of such.

Kull rode into the silent silvery streets of the ancient city, and the guards at the gate gaped at his appearance, but wisely refrained from questioning. He found the palace in an uproar. Swearing, he stalked to his council chamber and thence to the chamber of the cat Saremes. The cat was there, curled imperturbably on her cushion; and grouped about the chamber, each striving to talk down the others, were Tu and the chief councilors. The slave Kuthulos was nowhere to be seen.

Kull was greeted by a wild acclamation of shouts and questions, but he strode straight to Saremes’ cushion and glared at her. “Saremes,” said the king, “you lied to me.”

The cat stared at him coldly, yawned, and made no reply. Kull stood nonplussed, and Tu seized his arm.

“Kull, where in Valka’s name have you been? Whence this blood?”

Kull jerked loose irritably. “Leave be,” he snarled. “This cat sent me on a fool’s errand—where is Brule?”

“Kull!”

The king whirled and saw Brule stride through the door, his scanty garments stained by the dust of hard riding. The bronze features of the Pict were immobile, but his dark eyes gleamed with relief.

“Name of seven devils!” said the warrior testily, to hide his emotion. “My riders have combed the hills and the forest for you. Where have you been?”

“Searching the waters of Forbidden Lake for your worthless carcass,” answered Kull, with grim enjoyment at the Pict’s perturbation.

“Forbidden Lake!” Brule exclaimed with the freedom of the savage. “Are you in your dotage? What would I be doing there? I accompanied Ka-nu yesterday to the Zarfhaanian border and returned to hear Tu ordering out all the army to search for you. My men have since then ridden in every direction except the Forbidden Lake, where we never thought of going.”

“Saremes lied to me—” Kull began. But he was drowned out by a chatter of scolding voices, the main theme being that a king should never ride off so unceremoniously, leaving the kingdom to take care of itself.

“Silence!” roared Kull, lifting his arms, his eyes blazing dangerously. “Valka and Hotath! Am I an urchin to be rated for truancy? Tu, tell me what has occurred.”

In the sudden silence which followed his royal outburst, Tu began: “My lord, we have been duped from the beginning. This cat is, as I have maintained, a delusion and a dangerous fraud.”

“Yet—”

“My lord, have you never heard of men who could hurl their voices to a distance, making it appear that another spoke out, or that invisible voices sounded?”

Kull flushed. “Aye, by Valka! Fool that I should have forgotten! An old wizard of Lemuria had that gift. Yet who spoke—”

“Kuthulos!” exclaimed Tu. “Fool am I not to have remembered Kuthulos, a slave, aye, but the greatest scholar and the wisest man in all the Seven Empires. Slave of that she-fiend Delcardes who even now writhes on the rack!”

Kull gave a sharp exclamation.

“Aye,” said Tu grimly. “When I entered and found that you had ridden away, none knew where, I suspected treachery, and I sat down and thought hard. And I remembered Kuthulos and his art of voice-throwing and of how the false cat had told you small things but never great prophecies, giving false arguments for reason of refraining.

“So I knew that Delcardes had sent you this cat and Kuthulos to befool you and gain your confidence, and finally send you to your doom. So I sent for Delcardes and ordered her put to the torture so that she might confess all. She planned cunningly. Aye, Saremes must have her slave Kuthulos with her all the time—while he talked through her mouth and put strange ideas in your mind.”

“Then where is Kuthulos?” asked Kull.

“He had disappeared when I came to Saremes’ chamber, and—”

“Ho, Kull!” a cheery voice boomed from the door and a bearded, elfish figure strode in, accompanied by a slim, frightened girlish shape.

“Ka-nu! Delcardes! So they did not torture you after all!”

“Oh, my lord!” she ran to him and fell on her knees before him, clasping his feet. “Oh, Kull,” she wailed, “they accuse me of terrible things! I am guilty of deceiving you, my lord, but I meant no harm! I only wished to marry Kulra Thoom!”

Kull raised her to her feet, perplexed, but pitying her for her evident terror and remorse.

“Kull,” said Ka-nu, “it is a good thing I returned when I did, else you and Tu had tossed the kingdom into the sea!”

Tu snarled wordlessly, always jealous of the Pictish ambassador, who was also Kull’s adviser.

“I returned to find the whole palace in an uproar, men rushing hither and yon and falling over one another in doing nothing. I sent Brule and his riders to look for you, and going to the torture chamber—naturally I went first to the torture chamber, since Tu was in charge—”

The chancellor winced.

“Going to the torture chamber,” Ka-nu continued placidly, “I found them about to torture little Delcardes, who wept and told all she had to tell, but they did not believe her. She is only an inquisitive child, Kull, in spite of her beauty and all. So I brought her here.

“Now, Kull, Delcardes spoke truth when she said Saremes was her guest and that the cat was very ancient. True; she is a cat of the Old Race and wiser than other cats, going and coming as she pleases—but still a cat. Delcardes had spies in the palace to report to her such small things as the secret letter which you hid in your dagger sheath and the surplus in the treasury—the courtier who reported that was one of her spies and had discovered the surplus and told her before the royal treasurer knew. Her spies were your most loyal retainers; the things they told her harmed you not and aided her, whom they all love, for they knew she meant no harm.

“Her idea was to have Kuthulos, speaking through the mouth of Saremes, gain your confidence through small prophecies and facts which anyone might know, such as warning you against Thulsa Doom. Then, by constantly urging you to let Kulra Thoom marry Delcardes, to accomplish what was Delcardes’ only desire.”

“Then Kuthulos turned traitor,” said Tu.

And at that moment there was a noise at the chamber door, and guards entered, haling between them a tall, gaunt form, his face masked by a veil, his arms bound.

“Kuthulos!”

“Aye, Kuthulos,” said Ka-nu, but he seemed not at ease, and his eyes roved restlessly. “Kuthulos, no doubt, with his veil over his face to hide the workings of his mouth and neck muscles as he talked through Saremes.”

Kull eyed the silent figure which stood there like a statue. A silence fell over the group, as if a cold wind had passed over them. There was a tenseness in the atmosphere. Delcardes looked at the silent figure and her eyes widened as the guards told in terse sentences how the slave had been captured while trying to escape from the palace down a little used corridor.

Then a tense silence fell again as Kull stepped forward and reached forth a hand to tear the veil from the hidden face. Through the thin fabric Kull felt two eyes burn into his consciousness. None noticed Ka-nu clench his hands and tense himself as if for a terrific struggle.

Then as Kull’s hand almost touched the veil, a sudden sound broke the breathless silence—such a sound as a man might make by striking the floor with his forehead or elbow. The noise seemed to come from a wall, and Kull, crossing the room with a stride, smote against a panel from behind which the rapping sounded. A hidden door swung inward, revealing a dusty corridor, upon which lay the bound and gagged form of a man.

They dragged him forth and, standing him upright, unbound him.

“Kuthulos!” shrieked Delcardes.

Kull stared. The man’s face, now revealed, was thin and kindly, like a teacher of philosophy and morals.

“Yes my lords and lady,” he said. “That man who wears my veil stole upon me through the secret door, struck me down, and bound me. I lay there, hearing him send the king to what he thought was Kull’s death, but could do nothing.”

“Then who is he?” All eyes turned towards the veiled figure, and Kull stepped forward.

“Lord king, beware!” exclaimed the real Kuthulos. “He—”

Kull tore the veil away with one motion and recoiled with a gasp. Delcardes screamed and her knees gave way; the councilors pressed backwards, faces white, and the guards released their grasp and shrank away, horror-struck.

The face of the man was a bare white skull, in whose eye sockets flamed livid fire!

“Thulsa Doom! Aye, I guessed as much!” exclaimed Ka-nu.

“Aye, Thulsa Doom, fools,” the voice echoed cavernously. “The greatest of all wizards and your eternal foe, Kull of Atlantis. You have won this tilt, but beware, there shall be others.”

He burst the bonds on his arms with a single contemptuous gesture and stalked toward the door, the throng giving back before him.

“You are a fool of no discernment, Kull,” said he. “Else you had never mistaken me for that other fool, Kuthulos, even with the veil and his garments.”

Kull saw that it was so, for though the twain were alike in height and general shape, the flesh of the skull-faced wizard was like that of a man long dead.

The king stood, not fearful like the others, but so amazed at the turn of events that he was speechless. Then even as he sprang forward like a man waking from a dream, Brute charged with the silent ferocity of a tiger, his curved sword gleaming. And like a gleam of light it flashed into the ribs of Thulsa Doom, piercing him through and through, so that the point stood out between his shoulders.

Brule regained his blade with a quick wrench as he leaped back; then, crouching to strike again were it necessary, he halted. Not a drop of blood oozed from the wound which in a living man had been mortal. The skull-faced one laughed.

“Ages ago I died as men do!” he taunted. “Nay, I shall pass to some other sphere when my time comes, not before. I bleed not, for my veins are empty, and I feel only a slight coldness which shall pass when the wound closes, as it is even now closing. Stand back, fool, your master goes; but he shall come again to you, and you shall scream—and shrivel and die in that coming! Kull, I salute you!”

And while Brule hesitated, unnerved, and Kull halted in undecided amazement, Thulsa Doom stepped through the door and vanished before their very eyes.

“At least, Kull,” said Ka-nu later, “you have won your first tilt with the skull-faced one, as he admitted. Next time we must be more wary, for he is a fiend incarnate—an owner of magic black and unholy. He hates you, for he is a satellite of the great Serpent whose power you broke; he has the gift of illusion and of invisibility, which only he possesses. He is grim and terrible.”

“I fear him not,” said Kull. “The next time I will be prepared, and my answer shall be a sword thrust, even though he be unslayable, which thing I doubt. Brule did not find his vitals, which even a living dead man must have. That is all.”

Then, turning to Tu: “Lord Tu, it would seem that the civilized races also have their tabus since the blue lake is forbidden to all save myself.”

Tu answered testily, angry because Kull had given the happy Delcardes permission to marry whom she desired: “My lord, that is no heathen tabu such as your tribe bows to; it is a matter of statecraft, to preserve peace between Valusia and the lake-beings, who are magicians.”

“And we keep tabus so as not to offend unseen spirits of tigers and eagles,” said Kull. “And therein I see no difference.”

“At any rate,” said Tu, “you must beware of Thulsa Doom, for he vanished into another dimension, and as long as he is there he is invisible and harmless to us; but he will come again.”

“Ah, Kull,” sighed the old rascal, Ka-nu, “mine is a hard life compared to yours; Brule and I were drunk in Zarfhaana, and I fell down a flight of stairs, most damnably bruising my shins. And all the while you lounged in sinful ease on the silk of the kingship, Kull?”

Kull glared at him wordlessly and turned his back, giving his attention to the drowsing Saremes.

“She is not a wizard-beast, Kull,” said the Spear-slayer. “She is wise, but she merely looks her wisdom and does not speak. Yet her eyes fascinate me with their antiquity. A mere cat, just the same.”

“Still, Brule,” said Kull, admiringly stroking her silky fur, “still, she is a very ancient cat. Very.”