Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

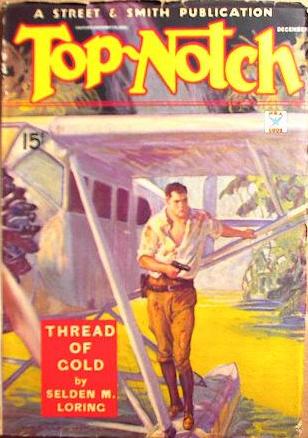

Published in Top-Notch, Vol. 95, No. 6 (December 1934).

| Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 |

Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 |

Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 |

“And now who will follow me to plunder greater than any of ye ever dreamed?”

“Show us!” demanded one of the hundred warriors. “Show us this plunder, before we slay thee.”

El Borak scoffed. “Shall I show you the stars by daylight?” he demanded. “Yet the stars are there, and men see them in their proper time. Follow me, and you shall see this plunder!”

“He lies!” came a voice from the warriors. “Let us slay him!”

El Borak looked them over with his steely eyes and asked pointedly, “And which of you shall lead?”

The tall Englishman, Pembroke, was scratching lines on the earth with his hunting knife, talking in a jerky tone that indicated suppressed excitement: “I tell you, Ormond, that peak to the west is the one we were to look for. Here, I’ve marked a map in the dirt. This mark here represents our camp, and this one is the peak. We’ve marched north far enough. At this spot we should turn westward—”

“Shut up!” muttered Ormond. “Rub out that map. Here comes Gordon.”

Pembroke obliterated the faint lines with a quick sweep of his open hand, and as he scrambled up he managed to shuffle his feet across the spot. He and Ormond were laughing and talking easily as the third man of the expedition came up.

Gordon was shorter than his companions, but his physique did not suffer by comparison with either the rangy Pembroke or the more closely knit Ormond. He was one of those rare individuals at once lithe and compact. His strength did not give the impression of being locked up within himself as is the case with so many strong men. He moved with a flowing ease that advertised power more subtly than does mere beefy bulk.

Though he was clad much like the two Englishmen except for an Arab headdress, he fitted into the scene as they did not. He, an American, seemed almost as much a part of these rugged uplands as the wild nomads which pasture their sheep along the slopes of the Hindu Kush. There was a certitude in his level gaze, and economy of motion in his movements, that reflected kinship with the wilderness.

“Pembroke and I were discussing that peak, Gordon,” said Ormond, indicating the mountain under discussion, which reared a snow cap in the clear afternoon sky beyond a range of blue hills, hazy with distance. “We were wondering if it had a name.”

“Everything in these hills has a name,” Gordon answered. “Some of them don’t appear on the maps, though. That peak is called Mount Erlik Khan. Less than a dozen white men have seen it.”

“Never heard of it,” was Pembroke’s comment. “If we weren’t in such a hurry to find poor old Reynolds, it might be fun having a closer look at it, what?”

“If getting your belly ripped open can be called fun,” returned Gordon. “Erlik Khan’s in Black Kirghiz country.”

“Kirghiz? Heathens and devil worshipers? Sacred city of Yolgan and all that rot.”

“No rot about the devil worship,” Gordon returned. “We’re almost on the borders of their country now. This is a sort of no man’s land here, squabbled over by the Kirghiz and Moslem nomads from farther east. We’ve been lucky not to have met any of the former. They’re an isolated branch off the main stalk which centers about Issik-kul, and they hate white men like poison.

“This is the closest point we approach their country. From now on, as we travel north, we’ll be swinging away from it. In another week, at most, we ought to be in the territory of the Uzbek tribe who you think captured your friend.”

“I hope the old boy is still alive.” Pembroke sighed.

“When you engaged me at Peshawar I told you I feared it was a futile quest,” said Gordon. “If that tribe did capture your friend, the chances are all against his being still alive. I’m just warning you, so you won’t be too disappointed if we don’t find him.”

“We appreciate that, old man,” returned Ormond. “We knew no one but you could get us there with our heads still on our bally shoulders.”

“We’re not there yet,” remarked Gordon cryptically, shifting his rifle under his arm. “I saw hangel sign before we went into camp, and I’m going to see if I can bag one. I may not be back before dark.”

“Going afoot?” inquired Pembroke.

“Yes; if I get one I’ll bring back a haunch for supper.”

And with no further comment Gordon strode off down the rolling slope, while the other men stared silently after him.

He seemed to melt rather than stride into the broad copse at the foot of the slope. The men turned, still unspeaking, and glanced at the servants going about their duties in the camp—four stolid Pathans and a slender Punjabi Moslem who was Gordon’s personal servant.

The camp with its faded tents and tethered horses was the one spot of sentient life in a scene so vast and broodingly silent that it was almost daunting. To the south, stretched an unbroken rampart of hills climbing up to snowy peaks. Far to the north rose another more broken range.

Between those barriers lay a great expanse of rolling table-land, broken by solitary peaks and lesser hill ranges, and dotted thickly with copses of ash, birch, and larch. Now, in the beginning of the short summer, the slopes were covered with tall lush grass. But here no herds were watched by turbaned nomads and that giant peak far to the southwest seemed somehow aware of that fact. It brooded like a somber sentinel of the unknown.

“Come into my tent!”

Pembroke turned away quickly, motioning Ormond to follow. Neither of them noticed the burning intensity with which the Punjabi Ahmed stared after them. In the tent, the men sitting facing each other across a small folding table, Pembroke took pencil and paper and began tracing a duplicate of the map he had scratched in the dirt.

“Reynolds has served his purpose, and so has Gordon,” he said. “It was a big risk bringing him, but he was the only man who could get us safely through Afghanistan. The weight that American carries with the Mohammedans is amazing. But it doesn’t carry with the Kirghiz, and beyond this point we don’t need him.

“That’s the peak the Tajik described, right enough, and he gave it the same name Gordon called it. Using it as a guide, we can’t miss Yolgan. We head due west, bearing a little to the north of Mount Erlik Khan. We don’t need Gordon’s guidance from now on, and we won’t need him going back, because we’re returning by the way of Kashmir, and we’ll have a better safe-conduct even than he. Question now is, how are we going to get rid of him?”

“That’s easy,” snapped Ormond; he was the harder-framed, the more decisive, of the two. “We’ll simply pick a quarrel with him and refuse to continue in his company. He’ll tell us to go to the devil, take his confounded Punjabi, and head back for Kabul—or maybe some other wilderness. He spends most of his time wandering around countries that are taboo to most white men.”

“Good enough!” approved Pembroke. “We don’t want to fight him. He’s too infernally quick with a gun. The Afghans call him ‘El Borak,’ the Swift. I had something of the sort in mind when I cooked up an excuse to halt here in the middle of the afternoon. I recognized that peak, you see. We’ll let him think we’re going on to the Uzbeks, alone, because, naturally, we don’t want him to know we’re going to Yolgan—”

“What’s that?” snapped Ormond suddenly, his hand closing on his pistol butt.

In that instant, when his eyes narrowed and his nostrils expanded, he looked almost like another man, as if suspicion disclosed his true—and sinister—nature.

“Go on talking,” he muttered. “Somebody’s listening outside the tent.”

Pembroke obeyed, and Ormond, noiselessly pushing back his camp chair, plunged suddenly out of the tent and fell on some one with a snarl of gratification. An instant later he re-entered, dragging the Punjabi, Ahmed, with him. The slender Indian writhed vainly in the Englishman’s iron grip.

“This rat was eavesdropping,” Ormond snarled.

“Now he’ll spill everything to Gordon and there’ll be a fight, sure!” The prospect seemed to agitate Pembroke considerably. “What’ll we do now? What are you going to do?”

Ormond laughed savagely. “I haven’t come this far to risk getting a bullet in my guts and losing everything. I’ve killed men for less than this.”

Pembroke cried out an involuntary protest as Ormond’s hand dipped and the blue-gleaming gun came up. Ahmed screamed, and his cry was drowned in the roar of the shot.

“Now we’ll have to kill Gordon!”

Pembroke wiped his brow with a hand that shook a trifle. Outside rose a sudden mutter of Pashto as the Pathan servants crowded toward the tent.

“He’s played into our hands!” rapped Ormond, shoving the still smoking gun back into his holster. With his booted toe he stirred the motionless body at his feet as casually as if it had been that of a snake. “He’s out on foot, with only a handful of cartridges. It’s just as well this turned out as it did.”

“What do you mean?” Pembroke’s wits seemed momentarily muddled.

“We’ll simply pack up and clear out. Let him try to follow us on foot, if he wants to. There are limits to the abilities of every man. Left in these mountains on foot, without food, blankets, or ammunition, I don’t think any white man will ever see Francis Xavier Gordon alive again.”

When Gordon left the camp he did not look behind him. Any thoughts of treachery on the part of his companions was furthest from his mind. He had no reason to suppose that they were anything except what they had represented themselves to be—white men taking a long chance to find a comrade the unmapped solitudes had swallowed up.

It was an hour or so after leaving the camp when, skirting the end of a grassy ridge, he sighted an antelope moving along the fringe of a thicket. The wind, such as there was, was blowing toward him, away from the animal. He began stalking it through the thicket, when a movement in the bushes behind him brought him around to the realization that he himself was being stalked.

He had a glimpse of a figure behind a clump of scrub, and then a bullet fanned his ear, and he fired at the flash and the puff of smoke. There was a thrashing among the foliage and then stillness. A moment later he was bending over a picturesquely clad form on the ground.

It was a lean, wiry man, young, with an ermine-edged khilat, a fur calpack, and silver-heeled boots. Sheathed knives were in his girdle, and a modern repeating rifle lay near his hand. He had been shot through the heart.

“Turkoman,” muttered Gordon. “Bandit, from his looks, out on a lone scout. I wonder how far he’s been trailing me.”

He knew the presence of the man implied two things: somewhere in the vicinity there was a band of Turkomans; and somewhere, probably close by, there was a horse. A nomad never walked far, even when stalking a victim. He glanced up at the rise which rolled up from the copse. It was logical to believe that the Moslem had sighted him from the crest of the low ridge, had tied his horse on the other side, and glided down into the thicket to waylay him while he stalked the antelope.

Gordon went up the slope warily, though he did not believe there were any other tribesmen within earshot—else the reports of the rifles would have brought them to the spot—and found the horse without trouble. It was a Turkish stallion with a red leather saddle with wide silver stirrups and a bridle heavy with goldwork. A scimitar hung from the saddle peak in an ornamented leather scabbard.

Swinging into the saddle, Gordon studied all quarters of the compass from the summit of the ridge. In the south a faint ribbon of smoke stood against the evening. His black eyes were keen as a hawk’s; not many could have distinguished that filmy blue feather against the cerulean of the sky.

“Turkoman means bandits,” he muttered. “Smoke means camp. They’re trailing us, sure as fate.”

Reining about, he headed for the camp. His hunt had carried him some miles east of the site, but he rode at a pace that ate up the distance. It was not yet twilight when he halted in the fringe of the larches and sat silently scanning the slope on which the camp had stood. It was bare. There was no sign of tents, men, or beasts.

His gaze sifted the surrounding ridges and clumps, but found nothing to rouse his alert suspicion. At last he walked his steed up the acclivity, carrying his rifle at the ready. He saw a smear of blood on the ground where he knew Pembroke’s tent had stood, but there was no other sign of violence, and the grass was not trampled as it would have been by a charge of wild horsemen.

He read the evidence of a swift but orderly exodus. His companions had simply struck their tents, loaded the pack animals, and departed. But why? Sight of distant horsemen might have stampeded the white men, though neither had shown any sign of the white feather before; but certainly Ahmed would not have deserted his master and friend.

As he traced the course of the horses through the grass, his puzzlement increased; they had gone westward.

Their avowed destination lay beyond those mountains in the north. They knew that, as well as he. But there was no mistake about it. For some reason, shortly after he had left camp, as he read the signs, they had packed hurriedly and set off westward, toward the forbidden country identified by Mount Erlik.

Thinking that possibly they had a logical reason for shifting camp and had left him a note of some kind which he had failed to find, Gordon rode back to the camp site and began casting about it in an ever-widening circle, studying the ground. And presently he saw sure signs that a heavy body had been dragged through the grass.

Men and horses had almost obliterated the dim track, but for years Gordon’s life had depended upon the keenness of his faculties. He remembered the smear of blood on the ground where Pembroke’s tent had stood.

He followed the crushed grass down the south slope and into a thicket, and an instant later he was kneeling beside the body of a man. It was Ahmed, and at first glance Gordon thought he was dead. Then he saw that the Punjabi, though shot through the body and undoubtedly dying, still had a faint spark of life in him.

He lifted the turbaned head and set his canteen to the blue lips. Ahmed groaned, and into his glazed eyes came intelligence and recognition.

“Who did this, Ahmed?” Gordon’s voice grated with the suppression of his emotions.

“Ormond Sahib,” gasped the Punjabi. “I listened outside their tent, because I feared they planned treachery to you. I never trusted them. So they shot me and have gone away, leaving you to die alone in the hills.”

“But why?” Gordon was more mystified than ever.

“They go to Yolgan,” panted Ahmed. “The Reynolds Sahib we sought never existed. He was a lie they created to hoodwink you.”

“Why to Yolgan?” asked Gordon.

But Ahmed’s eyes dilated with the imminence of death; in a racking convulsion he heaved up in Gordon’s arms; then blood gushed from his lips and he died.

Gordon rose, mechanically dusting his hands. Immobile as the deserts he haunted, he was not prone to display his emotions. Now he merely went about heaping stones over the body to make a cairn that wolves and jackals could not tear into. Ahmed had been his companion on many a dim road; less servant than friend.

But when he had lifted the last stone, Gordon climbed into the saddle, and without a backward glance he rode westward. He was alone in a savage country, without food or proper equipage. Chance had given him a horse, and years of wandering on the raw edges of the world had given him experience and a greater familiarity with this unknown land than any other white man he knew. It was conceivable that he might live to win his way through to some civilized outpost.

But he did not even give that possibility a thought. Gordon’s ideas of obligation, of debt and payment, were as direct and primitive as those of the barbarians among whom his lot had been cast for so many years. Ahmed had been his friend and had died in his service. Blood must pay for blood.

That was as certain in Gordon’s mind as hunger is certain in the mind of a gray timber wolf. He did not know why the killers were going toward forbidden Yolgan, and he did not greatly care. His task was to follow them to hell if necessary and exact full payment for spilled blood. No other course suggested itself.

Darkness fell and the stars came out, but he did not slacken his pace. Even by starlight it was not hard to follow the trail of the caravan through the high grass. The Turkish horse proved a good one and fairly fresh. He felt certain of overtaking the laden pack ponies, in spite of their long start.

As the hours passed, however, he decided that the Englishmen were determined to push on all night. They evidently meant to put so much distance between them and himself that he could never catch them, following on foot as they thought him to be. But why were they so anxious to keep from him the truth of their destination?

A sudden thought made his face grim, and after that he pushed his mount a bit harder. His hand instinctively sought the hilt of the broad scimitar slung from the high-peaked horn.

His gaze sought the white cap of Mount Erlik, ghostly in the starlight, then swung to the point where he knew Yolgan lay. He had been there before, himself, had heard the deep roar of the long bronze trumpets that shaven-headed priests blow from the mountains at sunrise.

It was past midnight when he sighted fires near the willow-massed banks of a stream. At first glance he knew it was not the camp of the men he followed. The fires were too many. It was an ordu of the nomadic Kirghiz who roam the country between Mount Erlik Khan and the loose boundaries of the Mohammedan tribes. This camp lay full in the path of Yolgan and he wondered if the Englishmen had known enough to avoid it. These fierce people hated strangers. He himself, when he visited Yolgan, had accomplished the feat disguised as a native.

Gaining the stream above the camp he moved closer, in the shelter of the willows, until he could make out the dim shapes of sentries on horseback in the light of the small fires. And he saw something else—three white European tents inside the ring of round, gray felt kibitkas. He swore silently; if the Black Kirghiz had killed the white men, appropriating their belongings, it meant the end of his vengeance. He moved nearer.

It was a suspicious, slinking, wolf-like dog that betrayed him. Its frenzied clamor brought men swarming out of the felt tents, and a swarm of mounted sentinels raced toward the spot, stringing bows as they came.

Gordon had no wish to be filled with arrows as he ran. He spurred out of the willows and was among the horsemen before they were aware of him, slashing silently right and left with the Turkish scimitar. Blades swung around him, but the men were more confused than he. He felt his edge grate against steel and glance down to split a broad skull; then he was through the cordon and racing into deeper darkness while the demoralized pack howled behind him.

A familiar voice shouting above the clamor told him that Ormond, at least, was not dead. He glanced back to see a tall figure cross the firelight and recognized Pembroke’s rangy frame. The fire gleamed on steel in his hands. That they were armed showed they were not prisoners, though this forbearance on the part of the fierce nomads was more than his store of Eastern lore could explain.

The pursuers did not follow him far; drawing in under the shadows of a thicket he heard them shouting gutturally to each other as they rode back to the tent. There would be no more sleep in that ordu that night. Men with naked steel in their hands would pace their horses about the encampment until dawn. It would be difficult to steal back for a long shot at his enemies. But now, before he slew them, he wished to learn what took them to Yolgan.

Absently his hand caressed the hawk-headed pommel of the Turkoman scimitar. Then he turned again eastward and rode back along the route he had come, as fast as he could push the wearying horse. It was not yet dawn when he came upon what he had hoped to find—a second camp, some ten miles west of the spot where Ahmed had been killed; dying fires reflected on one small tent and on the forms of men wrapped in cloaks on the ground.

He did not approach too near; when he could make out the lines of slowly moving shapes that were picketed horses and could see other shapes that were riders pacing about the camp, he drew back behind a thicketed ridge, dismounted and unsaddled his horse.

While it eagerly cropped the fresh grass, he sat cross-legged with his back to a tree trunk, his rifle across his knees, as motionless as an image and as imbued with the vast patience of the East as the eternal hills themselves.

Dawn was little more than a hint of grayness in the sky when the camp that Gordon watched was astir. Smoldering coals leaped up into flames again, and the scent of mutton stew filled the air. Wiry men in caps of Astrakhan fur and girdled caftans swaggered among the horse lines or squatted beside the cooking pots, questing after savory morsels with unwashed fingers. There were no women among them and scant luggage. The lightness with which they traveled could mean only one thing.

The sun was not yet up when they began saddling horses and belting on weapons. Gordon chose that moment to appear, riding leisurely down the ridge toward them.

A yell went up, and instantly a score of rifles covered him. The very boldness of his action stayed their fingers on the triggers. Gordon wasted no time, though he did not appear hurried. Their chief had already mounted, and Gordon reined up almost beside him. The Turkoman glared—a hawk-nosed, evil-eyed ruffian with a henna-stained beard. Recognition grew like a red flame in his eyes, and, seeing this, his warriors made no move.

“Yusef Khan,” said Gordon, “you Sunnite dog, have I found you at last?”

Yusef Khan plucked his red beard and snarled like a wolf. “Are you mad, El Borak?”

“It is El Borak!” rose an excited murmur from the warriors, and that gained Gordon another respite.

They crowded closer, their blood lust for the instant conquered by their curiosity. El Borak was a name known from Istanbul to Bhutan and repeated in a hundred wild tales wherever the wolves of the desert gathered.

As for Yusef Khan, he was puzzled, and furtively eyed the slope down which Gordon had ridden. He feared the white man’s cunning almost as much as he hated him, and in his suspicion, hate and fear that he was in a trap, the Turkoman was as dangerous and uncertain as a wounded cobra.

“What do you here?” he demanded. “Speak quickly, before my warriors strip the skin from you a little at a time.”

“I came following an old feud.” Gordon had come down the ridge with no set plan, but he was not surprised to find a personal enemy leading the Turkomans. It was no unusual coincidence. Gordon had blood-foes scattered all over Central Asia.

“You are a fool—”

In the midst of the chief’s sentence Gordon leaned from his saddle and struck Yusef Khan across the face with his open hand. The blow cracked like a bull whip and Yusef reeled, almost losing his seat. He howled like a wolf and clawed at his girdle, so muddled with fury that he hesitated between knife and pistol. Gordon could have shot him down while he fumbled, but that was not the American’s plan.

“Keep off!” he warned the warriors, yet not reaching for a weapon. “I have no quarrel with you. This concerns only your chief and me.”

With another man that would have had no effect; but another man would have been dead already. Even the wildest tribesman had a vague feeling that the rules governing action against ordinary feringhi did not apply to El Borak.

“Take him!” howled Yusef Khan. “He shall be flayed alive!”

They moved forward at that, and Gordon laughed unpleasantly.

“Torture will not wipe out the shame I have put upon your chief,” he taunted. “Men will say ye are led by a khan who bears the mark of El Borak’s hand in his beard. How is such shame to be wiped out? Lo, he calls on his warriors to avenge him! Is Yusef Khan a coward?”

They hesitated again and looked at their chief whose beard was clotted with foam. They all knew that to wipe out such an insult the aggressor must be slain by the victim in single combat. In that wolf pack even a suspicion of cowardice was tantamount to a death sentence.

If Yusef Khan failed to accept Gordon’s challenge, his men might obey him and torture the American to death at his pleasure, but they would not forget, and from that moment he was doomed.

Yusef Khan knew this; knew that Gordon had tricked him into a personal duel, but he was too drunk with fury to care. His eyes were red as those of a rabid wolf, and he had forgotten his suspicions that Gordon had riflemen hidden up on the ridge. He had forgotten everything except his frenzied passion to wipe out forever the glitter in those savage black eyes that mocked him.

“Dog!” he screamed, ripping out his broad scimitar. “Die at the hands of a chief!”

He came like a typhoon, his cloak whipping out in the wind behind him, his scimitar flaming above his head. Gordon met him in the center of the space the warriors left suddenly clear.

Yusef Khan rode a magnificent horse as if it were part of him, and it was fresh. But Gordon’s mount had rested, and it was well-trained in the game of war. Both horses responded instantly to the will of their riders.

The fighters revolved about each other in swift curvets and gambados, their blades flashing and grating without the slightest pause, turned red by the rising sun. It was less like two men fighting on horseback than like a pair of centaurs, half man and half beast, striking for one another’s life.

“Dog!” panted Yusef Khan, hacking and hewing like a man possessed of devils. “I’ll nail your head to my tent pole—ahhhh!”

Not a dozen of the hundred men watching saw the stroke, except as a dazzling flash of steel before their eyes, but all heard its crunching impact. Yusef Khan’s charger screamed and reared, throwing a dead man from the saddle with a split skull.

A wordless wolfish yell that was neither anger nor applause went up, and Gordon wheeled, whirling his scimitar about his head so that the red drops flew in a shower.

“Yusef Khan is dead!” he roared. “Is there one to take up his quarrel?”

They gaped at him, not sure of his intention, and before they could recover from the surprise of seeing their invincible chief fall, Gordon thrust his scimitar back in its sheath with a certain air of finality and said:

“And now who will follow me to plunder greater than any of ye ever dreamed?”

That struck an instant spark, but their eagerness was qualified by suspicion.

“Show us!” demanded one. “Show us the plunder before we slay thee.”

Without answering, Gordon swung off his horse and cast the reins to a mustached rider to hold, who was so astonished that he accepted the indignity without protest. Gordon strode over to a cooking pot, squatted beside it and began to eat ravenously. He had not tasted food in many hours.

“Shall I show you the stars by daylight?” he demanded, scooping out handfuls of stewed mutton, “Yet the stars are there, and men see them in the proper time. If I had the loot would I come asking you to share it? Neither of us can win it without the other’s aid.”

“He lies,” said one whom his comrades addressed as Uzun Beg. “Let us slay him and continue to follow the caravan we have been tracking.”

“Who will lead you?” asked Gordon pointedly.

They scowled at him, and various ruffians who considered themselves logical candidates glanced furtively at one another. Then all looked back at Gordon, unconcernedly wolfing down mutton stew five minutes after having slain the most dangerous swordsman of the black tents.

His attitude of indifference deceived nobody. They knew he was dangerous as a cobra that could strike like lightning in any direction. They knew they could not kill him so quickly that he would not kill some of them, and naturally none wanted to be first to die.

That alone would not have stopped them. But that was combined with curiosity, avarice roused by his mention of plunder, vague suspicion that he would not have put himself in a trap unless he held some sort of a winning hand, and jealousy of the leaders of each other.

Uzun Beg, who had been examining Gordon’s mount, exclaimed angrily: “He rides Ali Khan’s steed!”

“Aye,” Gordon assented tranquilly. “Moreover this is Ali Khan’s sword. He fired at me from ambush, so he lies dead.”

There was no answer. There was no feeling in that wolf pack except fear and hate, and respect for courage, craft, and ferocity.

“Where would you lead us?” demanded one named Orkhan Shan, tacitly recognizing Gordon’s dominance. “We be all free men and sons of the sword.”

“Ye be all sons of dogs,” answered Gordon. “Men without grazing lands or wives, outcasts, denied by thine own people—outlaws whose lives are forfeit, and who must roam in the naked mountains. You followed that dead dog without question. Now ye demand this and that of me!”

Then ensued a medley of argument among themselves, in which Gordon seemed to take no interest. All his attention was devoted to the cooking pot. His attitude was no pose; without swagger or conceit the man was so sure of himself that his bearing was no more self-conscious among a hundred cutthroats hovering on the hair line of murder than it would have been among friends.

Many eyes sought the gun butt at his hip. Men said his skill with the weapon was sorcery; an ordinary revolver became in his hand a living engine of destruction that was drawn and roaring death before a man could realize that Gordon’s hand had moved.

“Men say thou hast never broken thy word,” suggested Orkhan. “Swear to lead us to this plunder, and it may be we shall see.”

“I swear no oaths,” answered Gordon, rising and wiping his hands on a saddle cloth. “I have spoken. It is enough. Follow me, and many of you will die. Aye, the jackals will feed full. You will go up to the paradise of the prophet and your brothers will forget your names. But to those that live, wealth like the rain of Allah will fall upon them.”

“Enough of words!” exclaimed one greedily. “Lead us to this rare loot.”

“You dare not follow where I would lead,” he answered. “It lies in the land of the Kara Kirghiz.”

“We dare, by Allah!” they barked angrily. “We are already in the land of the Black Kirghiz, and we follow the caravan of some infidels, whom, inshallah, we shall send to hell before another sunrise.”

“Bismillah,” said Gordon. “Many of you shall eat arrows and edged steel before our quest is over. But if you dare stake your lives against plunder richer than the treasures of Hind, come with me. We have far to ride.”

A few minutes later the whole band was trotting westward. Gordon led, with lean riders on either hand; their attitude suggested that he was more prisoner than guide, but he was not perturbed. His confidence in his destiny had again been justified, and the fact that he had not the slightest idea of how to redeem his pledge concerning treasure disturbed him not at all. A way would be opened to him, somehow, and at present he did not even bother to consider it.

The fact that Gordon knew the country better than the Turkomans did aided him in his subtle policy to gain ascendency over them. From giving suggestions to giving orders and being obeyed is a short step, when delicately taken.

He took care that they kept below the sky lines as much as possible. It was not easy to hide the progress of a hundred men from the alert nomads; but these roamed far and there was a chance that only the band he had seen were between him and Yolgan.

But Gordon doubted this when they crossed a track that had been made since he rode eastward the night before. Many riders had passed that point, and Gordon urged greater speed, knowing that if they were spied by the Kirghiz instant pursuit was inevitable.

In the late afternoon they came in sight of the ordu beside the willow-lined stream. Horses tended by youngsters grazed near the camp, and farther away the riders watched the sheep which browsed through the tall grass.

Gordon had left all his men except half a dozen in a thicket-massed hollow behind the next ridge, and he now lay among a cluster of boulders on a slope overlooking the valley. The encampment was beneath him, distinct in every detail, and he frowned. There was no sign of the white tents. The Englishmen had been there. They were not there now. Had their hosts turned on them at last, or had they continued alone toward Yolgan?

The Turkomans, who did not doubt that they were to attack and loot their hereditary enemies, began to grow impatient.

“Their fighting men are less than ours,” suggested Uzun Beg, “and they are scattered, suspecting nothing. It is long since an enemy invaded the land of the Black Kirghiz. Send back for the others, and let us attack. You promised us plunder.”

“Flat-faced women and fat-tailed sheep?” Gordon jeered.

“Some of the women are fair to look at,” the Turkoman maintained. “And we could feast full on the sheep. But these dogs carry gold in their wagons to trade to merchants from Kashmir. It comes from Mount Erlik Khan.”

Gordon remembered that he had heard tales of a gold mine in Mount Erlik before, and he had seen some crudely cast ingots the owners of which swore they had them from the Black Kirghiz. But gold did not interest him just then.

“That is a child’s tale,” he said, at least half believing what he said. “The plunder I will lead you to is real, would you throw it away for a dream? Go back to the others and bid them stay hidden. Presently I will return.”

They were instantly suspicious, and he saw it.

“Return thou, Uzun Beg,” he said, “and give the others my message. The rest of you come with me.”

That quieted the hair-trigger suspicions of the five, but Uzun Beg grumbled in his beard as he strode back down the slope, mounted and rode eastward. Gordon and his companions likewise mounted behind the crest and, keeping below the sky line, they followed the ridge around as it slanted toward the southwest.

It ended in sheer cliffs, as if it had been sliced off with a knife, but dense thickets hid them from the sight of the camp as they crossed the space that lay between the cliffs and the next ridge, which ran to a bend in the stream, a mile below the ordu.

This ridge was considerably higher than the one they had left, and before they reached the point where it began to slope downward toward the river, Gordon crawled to the crest and scanned the camp again with a pair of binoculars that had once been the property of Yusef Khan.

The nomads showed no sign that they suspected the presence of enemies, and Gordon turned his glasses farther eastward, located the ridge beyond which his men were concealed, but saw no sign of them. But he did see something else.

Miles to the east a knife-edge ridge cut the sky, notched with a shallow pass. As he looked he saw a string of black dots moving through that notch. It was so far away that even the powerful glasses did not identify them, but he knew what the dots were—mounted men, many of them.

Hurrying back to his five Turkomans, he said nothing, but pressed on, and presently they emerged from behind the ridge and came upon the stream where it wound out of sight of the encampment. Here was the logical crossing for any road leading to Yolgan, and it was not long before he found what he sought.

In the mud at the edges of the stream were the prints of shod hoofs and at one spot the mark of a European boot. The Englishmen had crossed here; beyond the ford their trail lay west, across the rolling table-land.

Gordon was puzzled anew. He had supposed that there was some particular reason why this clan had received the Englishmen in peace. He had reasoned that Ormond would persuade them to escort him to Yolgan. Though the clans made common cause against invaders, there were feuds among themselves, and the fact that one tribe received a man in peace did not mean that another tribe would not cut his throat.

Gordon had never heard of the nomads of this region showing friendship to any white man. Yet the Englishmen had passed the night in that ordu and now plunged boldly on as if confident of their reception. It looked like utter madness.

As he meditated, a distant sputter of rifle fire jerked his head up. He splashed across the stream and raced up the slope that hid them from the valley, with the Turkomans at his heels working the levers of their rifles. As he topped the slope he saw the scene below him crystal-etched in the blue evening.

The Turkomans were attacking the Kirghiz camp. They had crept up the ridge overlooking the valley, and then swept down like a whirlwind. The surprise had been almost, but not quite, complete. Outriding shepherds had been shot down and the flocks scattered, but the surviving nomads had made a stand within the ring of their tents and wagons.

Ancient matchlocks, bows, and a few modern rifles answered the fire of the Turkomans. These came on swiftly, shooting from the saddle, only to wheel and swerve out of close range again.

The Kirghiz were protected by their cover, but even so the hail of lead took toll. A few saddles were emptied, but the Turkomans were hard hit on their prancing horses, as the riders swung their bodies from side to side.

Gordon gave his horse the rein and came galloping across the valley, his scimitar glittering in his hand. With his enemies gone from the camp, there was no reason for attacking the Kirghiz now as he had planned. But the distance was too great for shouted orders to be heard.

The Turkomans saw him coming, sword in hand, and mistook his meaning. They thought he meant to lead a charge, and in their zeal they anticipated him.

They were aided by the panic which struck the Kirghiz as they saw Gordon and his five Turkomans sweep down the slope and construed it as an attack in force on their flank.

Instantly they directed all their fire at the newcomers, emptying the clumsy matchlocks long before Gordon was even within good rifle range. And as they did, the Turkomans charged home with a yell that shook the valley, preceded by a withering fire as they blazed away over their horses’ ears.

This time no ragged volleys could stop them. In their panic the tribesmen had loosed all their firearms at once, and the charge caught them with matchlocks and muskets empty. A straggling rifle fire met the oncoming raiders and knocked a few out of their saddles, and a flight of arrows accounted for a few more, but then the charge burst on the makeshift barricade and crumpled it. The howling Turkomans rode their horses in among the tents, flailing right and left with scimitars already crimson.

For an instant hell raged in the ordu, then the demoralized nomads broke and fled as best they could, being cut down and trampled by the conquerors. Neither women nor children were spared by the blood-mad Turks. Such as could slipped out of the ring and ran wailing for the river. An instant later the riders were after them like wolves.

Yet, winged by the fear of death, a disorderly mob reached the shore first, broke through the willows and plunged screaming over the low bank, trampling each other in the water. Before the Turkomans could rein their horses over the bank, Gordon arrived, with his horse plastered with sweat and snorting foam.

Enraged at the wanton slaughter, Gordon was an incarnation of berserk fury. He caught the first man’s bridle and threw his horse back on its haunches with such violence that the beast lost its footing and fell, sprawling, throwing its rider. The next man sought to crowd past, giving tongue like a wolf, and him Gordon smote with the flat of his scimitar. Only the heavy fur cap saved the skull beneath, and the man pitched, senseless, from his saddle. The others yelled and reined back suddenly.

Gordon’s wrath was like a dash of ice-cold water in their faces, shocking their blood-mad nerves into stinging sensibility. From among the tents cries still affronted the twilight, with the butcherlike chopping of merciless sword blows, but Gordon gave no heed. He could save no one in the plundered camp, where the howling warriors were ripping the tents to pieces, overturning the wagons and setting the torch in a hundred places.

More and more men with burning eyes and dripping blades were streaming toward the river, halting as they saw El Borak barring their way. There was not a ruffian there who looked half as formidable as Gordon did in that instant. His lips snarled and his eyes were black coals of hell’s fire.

There was no play acting about it. His mask of immobility had fallen, revealing the sheer primordial ferocity of the soul beneath. The dazed Turkomans, still dizzy from the glutting of their blood lust, weary from striking great blows, and puzzled by his attitude, shrank back from him.

“Who gave the order to attack?” he yelled, and his voice was like the slash of a saber.

He trembled in the intensity of his passion. He was a blazing flame of fury and death, without control or repression. He was as wild and brute-savage in that moment as the wildest barbarian in that raw land.

“Uzun Beg!” cried a score of voices, and men pointed at the scowling warrior. “He said that you had stolen away to betray us to the Kirghiz, and that we should attack before they had time to come upon us and surround us. We believed him until we saw you riding over the slope.”

With a wordless fierce yell like the scream of a striking panther, Gordon hurled his horse like a typhoon on Uzun Beg, smiting with his scimitar. Uzun Beg catapulted from his saddle with his skull crushed, dead before he actually realized that he was menaced.

El Borak wheeled on the others and they reined back from him, scrambling in terror.

“Dogs! Jackals! Noseless apes! Forgotten of God!” he lashed them with words that burned like scorpions. “Sons of nameless curs! Did I not bid you keep hidden? Is my word wind—a leaf to be blown away by the breath of a dog like Uzun Beg? Now you have lapped up needless blood, and the whole countryside will be riding us down like jackals. Where is your loot? Where is the gold with which the wagons were laden?”

“There was no gold,” muttered a tribesman, mopping blood from a sword cut.

They flinched from the savage scorn and anger in Gordon’s baying laughter.

“Dogs that nuzzle in the dung heaps of hell! I should leave you to die.”

“Slay him!” mouthed a tribesman. “Shall we eat of an infidel? Slay him and let us go back whence we came. There is no loot in this naked land.”

The proposal was not greeted with enthusiasm. Their rifles were all empty, some even discarded in the fury of sword strokes. They knew the rifle under El Borak’s knee was loaded and the pistol at his hip. Nor did any of them care to ride into the teeth of that reddened scimitar that swung like a live thing in his right hand.

Gordon saw their indecision and mocked them. He did not argue or reason as another man might have done. And if he had, they would have killed him. He beat down opposition with curses, abuses, and threats that were convincing because he meant every word he spat at them. They submitted because they were a wolf pack, and he was the grimmest wolf of them all.

Not one man in a thousand could have bearded them as he did and lived. But there was a driving elemental power about him that shook resolution and daunted anger—something of the fury of an unleashed torrent or a roaring wind that hammered down will power by sheer ferocity.

“We will have no more of thee,” the boldest voiced the last spark of rebellion. “Go thy ways, and we will go ours.”

Gordon barked a bitter laugh. “Thy ways lead to the fires of Jehannum!” he taunted bitterly. “Ye have spilled blood, and blood will be demanded in payment. Do you dream that those who have escaped will not flee to the nearest tribes and raise the countryside? You will have a thousand riders about your ears before dawn.”

“Let us ride eastward,” one said nervously. “We will be out of this land of devils before the alarm is raised.”

Again Gordon laughed and men shivered. “Fools! You cannot return. With the glasses I have seen a body of horsemen following our trail. Ye are caught in the fangs of the vise. Without me you cannot go onward; if you stand still or go back, none of you will see another sun set.”

Panic followed instantly which was more difficult to fight down than rebellion.

“Slay him!” howled one. “He has led us into a trap!”

“Fools!” cried Orkhan Shah, who was one of the five Gordon had led to the ford. “It was not he who tricked you into charging the Kirghiz. He would have led us on to the loot he promised. He knows this land and we do not. If ye slay him now, ye slay the only man who may save us!”

That spark caught instantly, and they clamored about Gordon.

“The wisdom of the sahibs is thine! We be dogs who eat dirt! Save us from our folly! Lo, we obey thee! Lead us out of this land of death, and show us the gold whereof thou spokest!”

Gordon sheathed his scimitar and took command without comment. He gave orders and they were obeyed. Once these wild men, in their fear, turned to him, they trusted him implicitly. They knew he was somehow using them ruthlessly in his own plans, but that was nothing more than any one of them would have done had he been able. In that wild land only the ways of the wolf pack prevailed.

As many Kirghiz horses as could be quickly caught were rounded up. On some of them food and articles of clothing from the looted camp were hastily tied. Half a dozen Turkomans had been killed, nearly a dozen wounded. The dead were left where they had fallen. The most badly wounded were tied to their saddles, and their groans made the night hideous. Darkness had fallen as the desperate band rode over the slope and plunged across the river. The wailing of the Kirghiz women, hidden in the thickets, was like the dirging of lost souls.

Gordon did not attempt to follow the trail of the Englishmen over the comparatively level table-land. Yolgan was his destination and he believed he would find them there, but there was desperate need to escape the tribesmen who he was certain were following them, and who would be lashed to fiercer determination by what they would find in the camp by the river.

Instead of heading straight across the table-land, Gordon swung into the hills that bordered it on the south and began following them westward. Before midnight one of the wounded men died in his saddle, and some of the others were semidelirious. They hid the body in a crevice and went on. They moved through the darkness of the hills like ghosts; the only sounds were the clink of hoofs on stone and the groans of the wounded.

An hour before dawn they came to a stream which wound between limestone ledges, a broad shallow stream with a solid rock bottom. They waded their horses along it for three miles, then climbed out again on the same side.

Gordon knew that the Kirghiz, smelling out their trail like wolves, would follow them to the bank and expect some such ruse as an effort to hide their tracks. But he hoped that the nomads would be expecting them to cross the stream and plunge into the mountains on the other side and would therefore waste time looking for tracks along the south bank.

He now headed westward in a more direct route. He did not expect to throw the Kirghiz entirely off the scent. He was only playing for time. If they lost his trail, they would search in any direction first except toward Yolgan, and to Yolgan he must go, since there was now no chance of catching his enemies on the road.

Dawn found them in the hills, a haggard, weary band. Gordon bade them halt and rest and, while they did so, he climbed the highest crag he could find and patiently scanned the surrounding cliffs and ravines with his binoculars, while he chewed tough strips of dried mutton which the tribesmen carried between saddle and saddlecloth to keep warm and soft. He alternated with cat naps of ten or fifteen minutes’ duration, storing up concentrated energy as men of the outlands learn to do, and between times watching the ridges for signs of pursuit.

He let the men rest as long as he dared, and the sun was high when he descended the rock and stirred them into wakefulness. Their steel-spring bodies had recovered some of their resilience, and they rose and saddled with alacrity, all except one of the wounded men, who had died in his sleep. They lowered his body into a deep fissure in the rocks and went on, more slowly, for the horses felt the grind more than the men.

All day they threaded their way through wild gorges overhung by gloomy crags. The Turkomans were crowded by the grim desolation and the knowledge that a horde of bloodthirsty barbarians were on their trail. They followed Gordon without question as he led them, turning and twisting, along dizzy heights and down into the abysmal gloom of savage gorges, then up turreted ridges again and around windswept shoulders.

He had used every artifice known to him to shake off pursuit and was making for his set goal as fast as possible. He did not fear encountering any clans in these bare hills; they grazed their flocks on the lower levels. But he was as familiar with the route he was following as his men thought.

He was feeling his way, mostly by the instinct for direction that men who live in the open possess, but he would have been lost a dozen times but for glimpses of Mount Erlik Khan shouldering up above the surrounding hills in the distance.

As they progressed westward he recognized other landmarks, seen from new angles, and just before sunset he glimpsed a broad shallow valley, across the pine-grown slopes of which he saw the walls of Yolgan looming against the crags behind it.

Yolgan was built at the foot of a mountain, overlooking the valley through which a stream wandered among masses of reeds and willows. Timber was unusually dense. Rugged mountains, dominated by Erlik’s peak to the south, swept around the valley to the south and west, and in the north it was blocked by a chain of hills. To the east it was open, sloping down from a succession of uneven ridges. Gordon and his men had followed the ranges in their flight, and now they looked down on the valley from the south.

El Borak led the warriors down from the higher crags and hid them on one of the many gorges debouching on the lower slopes, not more than a mile and a half from the city itself. It ended in a cul-de-sac and suggested a trap, but the horses were ready to fall from exhaustion, the men’s canteens were empty, and a spring gurgling out of the solid rock decided Gordon.

He found a ravine leading out of the gorge and placed men on guard there, as well as at the gorge mouth. It would serve as an avenue of escape if need be. The men gnawed the scraps of food that remained, and dressed their wounds as best they could. When he told them he was going on a solitary scout they looked at him with lack-luster eyes, in the grip of the fatalism that is the heritage of the Turkish races.

They did not mistrust him, but they felt like dead men already. They looked like ghouls, with their dusty, torn garments, clotted with dried blood, and sunken eyes of hunger and weariness. They squatted or lay about, wrapped in their tattered cloaks, unspeaking.

Gordon was more optimistic than they. Perhaps they had not completely eluded the Kirghiz, but he believed it would take some time for even those human bloodhounds to ferret them out, and he did not fear discovery by the inhabitants of Yolgan. He knew they seldom wandered into the hills.

Gordon had neither slept nor eaten as much as his men, but his steely frame was more enduring than theirs, and he was animated by a terrific vitality that would keep his brain clear and his body vibrant long after another man had dropped in his tracks.

It was dark when Gordon strode on foot out of the gorge, the stars hanging over the peaks like points of chilled silver. He did not strike straight across the valley, but kept to the line of marching hills. So it was no great coincidence that he discovered the cave where men were hidden.

It was situated in a rocky shoulder that ran out into the valley, and which he skirted rather than clamber over. Tamarisk grew thickly about it, masking the mouth so effectually that it was only by chance that he glimpsed the reflection of a fire against a smooth inner wall.

Gordon crept through the thickets and peered in. It was a bigger cave than the mouth indicated. A small fire was going, and three men squatted by it, eating and conversing in guttural Pashto. Gordon recognized three of the camp servants of the Englishmen. Farther back in the cave he saw the horses and heaps of camp equipment. The mutter of conversation was unintelligible where he crouched, and even as he wondered where the white men and the fourth servant were, he heard someone approaching.

He drew back farther into the shadows and waited, and presently a tall figure loomed in the starlight. It was the other Pathan, his arms full of firewood.

As he strode toward the natural camp which led up the cave mouth, he passed so close to Gordon’s hiding place that the American could have touched him with an extended arm. But he did not extend an arm; he sprang on the man’s back like a panther on a buck.

The firewood was knocked in all directions and the two men rolled together down a short grassy slope, but Gordon’s fingers were digging into the Pathan’s bull throat, strangling his efforts to cry out, and the struggle made no noise that could have been heard inside the cave above the crackle of the tamarisk chunks.

The Pathan’s superior height and weight were futile against the corded sinews and wrestling skills of his opponent. Heaving the man under him, Gordon crouched on his breast and throttled him dizzy before he relaxed his grasp and let life and intelligence flow back into his victim’s dazed brain.

The Pathan recognized his captor and his fear was the greater, because he thought he was in the hands of a ghost. His eyes glimmered in the gloom and his teeth shone in the black tangle of his beard.

“Where are the Englishmen?” demanded Gordon softly. “Speak, you dog, before I break your neck!”

“They went at dusk toward the city of devils!” gasped the Pathan.

“Prisoners?”

“Nay; one with a shaven head guided them. They bore their weapons and were not afraid.”

“What are they doing here?”

“By Allah, I do not know!”

“Tell me all you do know,” commanded Gordon. “But speak softly. If your mates hear and come forth, you will suddenly cease to be. Begin where I went forth to shoot the stag. After that, Ormond killed Ahmed. That I know.”

“Aye; it was the Englishman. I had naught to do with it. I saw Ahmed lurking outside Pembroke Sahib’s tent. Presently Ormond Sahib came forth and dragged him in the tent. A gun spoke, and when we went to look, the Punjabi lay dead on the floor of the tent.

“Then the sahibs bade us strike the tents and load the pack horses, and we did so without question. We went westward in great haste. When the night was not yet half over, we sighted a camp of pagans, and my brothers and I were much afraid. But the sahibs went forward, and when the accursed ones came forth with arrows on string, Ormond Sahib held up a strange emblem which glowed in the light of the torches, whereupon the heathens dismounted and bowed to the earth.

“We abode in their camp that night. In the darkness someone came to the camp and there was fighting and a man slain, and Ormond Sahib said it was a spying Turkoman, and that there would be fighting, so at dawn we left the pagans and went westward in haste, across the ford. When we met other heathen, Ormond showed them the talisman, and they did us honor. All day we hastened, driving the beasts hard, and when night fell we did not halt, for Ormond Sahib was like one mad. So before the night was half gone, we came into this valley, and the sahibs hid us in this cave.

“Here we abode until a pagan passed near the cavern this morning, driving sheep. Then Ormond Sahib called to him and showed him the talisman and made it known that he wished speech with the priest of the city. So the man went, and presently he returned with the priest who could speak Kashmiri. He and the sahibs talked long together, but what they said I know not. But Ormond Sahib killed the man who had gone to fetch the priest, and he and the priest hid the body with stones.

“Then after more talk, the priest went away, and the sahibs abode in the cave all day. But at dusk another man came to them, a man with a shaven head and camel’s hair robes, and they went with him toward the city. They bade us eat and then saddle and pack the animals, and be ready to move with great haste between midnight and dawn. That is all I know, as Allah is my witness.”

Gordon made no reply. He believed the man was telling the truth, and his bewilderment grew. As he meditated on the tangle, he unconsciously relaxed his grip, and the Pathan chose that instant to make his break for freedom. With a convulsive heave he tore himself partly free of Gordon’s grasp, whipped from his garments a knife he had been unable to reach before, and yelled loudly as he stabbed.

Gordon avoided the thrust by a quick twist of his body; the edge slit his shirt and the skin beneath, and stung by its bite and his peril, he caught the Pathan’s bull neck in both hands and put all his strength into a savage wrench. The man’s spinal column snapped like a rotten branch, and Gordon flung himself over backward into the thicker shadows as a man bulked black in the mouth of the cavern. The fellow called a cautious query, but Gordon waited for no more. He was already gone like a phantom into the gloom.

The Pathan repeated his call and then, getting no response, summoned his mates in some trepidation. With weapons in their hands they stole down the ramp, and presently one of them stumbled over the body of their companion. They bent over it, muttering affrightedly.

“This is a place of devils,” said one. “The devils have slain Akbar.”

“Nay,” said another. “It is the people of this valley. They mean to slay us one by one.” He grasped his rifle and stared fearsomely into the shadows that hemmed them in. “They have bewitched the sahibs and led them away to be slain,” he muttered.

“We will be next,” said the third. “The sahibs are dead. Let us load the animals and go away quickly. Better die in the hills than wait like sheep for our throats to be cut.”

A few minutes later they were hurrying eastward through the pines as fast as they could urge the beasts.

Of this Gordon knew nothing. When he left the slope below the cave he did not follow the trend of the hills as before, but headed straight through the pines toward the lights of Yolgan. He had not gone far when he struck a road from the east leading toward the city. It wound among the pines, a slightly less dark thread in a bulwark of blackness.

He followed it to within easy sight of the great gate which stood open in the dark and massive walls of the town. Guards leaned carelessly on their matchlocks. Yolgan feared no attack. Why should it? The wildest of the Mohammedan tribes shunned the land of the devil worshipers. Sounds of barter and dispute were wafted by the night wind through the gate.

Somewhere in Yolgan, Gordon was sure, were the men he was seeking. That they intended returning to the cave he had been assured. But there was a reason why he wished to enter Yolgan, a reason not altogether tied up with vengeance. As he pondered, hidden in the deep shadow, he heard the soft clop of hoofs on the dusty road behind him. He slid farther back among the pines; then with a sudden thought he turned and made his way beyond the first turn, where he crouched in the blackness beside the road.

Presently a train of laden pack mules came along, with men before and behind and at either side. They bore no torches, moving like men who knew their path. Gordon’s eyes had so adjusted themselves to the faint starlight of the road that he was able to recognize them as Kirghiz herdsmen in their long cloaks and round caps. They passed so close to him that their body-scent filled his nostrils.

He crouched lower in the blackness, and as the last man moved past him, a steely arm hooked fiercely about the Kirghiz’s throat, choking his cry. An iron fist crunched against his jaw and he sagged senseless in Gordon’s arms. The others were already out of sight around the bend of the trail, and the scrape of the mules’ bulging packs against the branches along the road was enough to drown the slight noises of the struggle.

Gordon dragged his victim in under the black branches and swiftly stripped him, discarding his own boots and kaffiyeh and donning the native’s garments, with pistol and scimitar buckled on under the long cloak. A few minutes later he was moving along after the receding column, leaning on his staff as with the weariness of long travel. He knew the man behind him would not regain consciousness for hours.

He came up with the tail of the train, but lagged behind as a straggler might. He kept close enough to the caravan to be identified with it, but not so close as to tempt conversation or recognition by the other members of the train. When they passed through the gate none challenged him. Even in the flare of the torches under the great gloomy arch he looked like a native, with his dark features fitting in with his garments and the lambskin cap.

As he went down the torch-lighted street, passing unnoticed among the people who chattered and argued in the markets and stalls, he might have been one of the many Kirghiz shepherds who wandered about, gaping at the sights of the city which to them represented the last word in the metropolitan.

Yolgan was not like any other city in Asia. Legend said it was built long ago by a cult of devil worshipers who, driven from their distant homeland, had found sanctuary in this unmapped country, where an isolated branch of the Black Kirghiz, wilder than their kinsmen, roamed as masters. The people of the city were a mixed breed, descendants of these original founders and the Kirghiz.

Gordon saw the monks who were the ruling caste in Yolgan striding through the bazaars—tall, shaven-headed men with Mongolian features. He wondered anew as to their exact origin. They were not Tibetans. Their religion was not a depraved Buddhism. It was unadulterated devil worship. The architecture of their shrines and temples differed from any he had ever encountered anywhere.

But he wasted no time in conjecture, nor in aimless wandering. He went straight to the great stone building squatted against the side of the mountain at the foot of which Yolgan was built. Its great blank curtains of stone seemed almost like part of the mountain itself.

No one hindered him. He mounted a long flight of steps that were at least a hundred feet wide, bending over his staff as with the weariness of a long pilgrimage. Great bronze doors stood open, unguarded, and he kicked off his sandals and came into a huge hall the inner gloom of which was barely lighted by dim brazen lamps in which melted butter was burned.

Shaven-headed monks moved through the shadows like dusky ghosts, but they gave him no heed, thinking him merely a rustic worshiper come to leave some humble offering at the shrine of Erlik, Lord of the Seventh Hell.

At the other end of the hall, view was cut off by a great divided curtain of gilded leather that hung from the lofty roof to the floor. Half a dozen steps that crossed the hall led up to the foot of the curtain, and before it a monk sat cross-legged and motionless as a statue, arms folded and head bent as if in communion with unguessed spirits.

Gordon halted at the foot of the steps, made as if to prostrate himself, then retreated as if in sudden panic. The monk showed no interest. He had seen too many nomads from the outer world overcome by superstitious awe before the curtain that hid the dread effigy of Erlik Khan. The timid Kirghiz might skulk about the temple for hours before working up nerve enough to make his devotions to the deity. None of the priests paid any attention to the man in the caftan of a shepherd who slunk away as if abashed.

As soon as he was confident that he was not being watched, Gordon slipped through a dark doorway some distance from the gilded curtain and groped his way down a broad unlighted hallway until he came to a flight of stairs. Up this he went with both haste and caution and came presently into a long corridor along which winked sparks of light, like fireflies in a runnel.

He knew these lights were tiny lamps in the small cells that lined the passage, where the monks spent long hours in contemplation of dark mysteries, or pored over forbidden volumes, the very existence of which is not suspected by the outer world. There was a stair at the nearer end of the corridor, and up this he went, without being discovered by the monks in their cells. The pin points of light in the chambers did not serve to illuminate the darkness of the corridor to any extent.

As Gordon approached a crook in the stair he renewed his caution, for he knew there would be a man on guard at the head of the steps. He knew also that he would be likely to be asleep. The man was there—a half-naked giant with the wizened features of a deaf mute. A broad-tipped tulwar lay across his knees and his head rested on it as he slept.

Gordon stole noiselessly past him and came into an upper corridor which was dimly lighted by brass lamps hung at intervals. There were no doorless cells here, but heavy bronze-bound teak portals flanked the passage. Gordon went straight to one which was particularly ornately carved and furnished with an unusual fretted arch by way of ornament. He crouched there listening intently, then took a chance and rapped softly on the door. He rapped nine times, with an interval between each three raps.

There was an instant’s tense silence, then an impulsive rush of feet across a carpeted floor, and the door was jerked open. A magnificent figure stood framed in the soft light. It was a woman, a lithe, splendid creature whose vibrant figure exuded magnetic vitality. The jewels that sparkled in the girdle about her supple hips were no more scintillant than her eyes.

Instant recognition blazed in those eyes, despite his native garments. She caught him in a fierce grasp. Her slender arms were strong as pliant steel.

“El Borak! I knew you would come!”

Gordon stepped into the chamber and closed the door behind him. A quick glance showed him there was no one there but themselves. Its thick Persian rugs, silk divans, velvet hangings, and gold-chased lamps struck a vivid contrast with the grim plainness of the rest of the temple. Then he turned his full attention again to the woman who stood before him, her white hands clenched in a sort of passionate triumph.

“How did you know I would come, Yasmeena?” he asked.

“You never failed a friend in need,” she answered.

“Who is in need?”

“I!”

“But you are a goddess!”

“I explained it all in my letter!” she exclaimed bewilderedly.

Gordon shook his head. “I have received no letter.”

“Then why are you here?” she demanded in evident puzzlement.

“It’s a long story,” he answered. “Tell me first why Yasmeena, who had the world at her feet and threw it away for weariness to become a goddess in a strange land, should speak of herself as one in need.”

“In desperate need, El Borak.” She raked back her dark locks with a nervously quick hand. Her eyes were shadowed with weariness and something more, something which Gordon had never seen there before—the shadow of fear.

“Here is food you need more than I,” she said as she sank down on a divan and with a dainty foot pushed toward him a small gold table on which were chupaties, curried rice, and broiled mutton, all in gold vessels, and a gold jug of kumiss.

He sat down without comment and began to eat with unfeigned gusto. In his drab camel’s-hair caftan, with the wide sleeves drawn back from his corded brown arms, he looked out of place in that exotic chamber.

Yasmeena watched him broodingly, her chin resting on her hand, her somber eyes enigmatic.

“I did not have the world at my feet, El Borak,” she said presently. “But I had enough of it to sicken me. It became a wine which had lost its savor. Flattery became like an insult; the adulation of men became an empty repetition without meaning. I grew maddeningly weary of the flat fool faces that smirked eternally up at me, all wearing the same sheep expressions and animated by the same sheep thoughts. All except a few men like you, El Borak, and you were wolves in the flock. I might have loved you, El Borak, but there is something too fierce about you; your soul is a whetted blade on which I feared I might cut myself.”

He made no reply, but tilted the golden jug and gulped down enough stinging kumiss to have made an ordinary man’s head swim at once. He had lived the life of the nomads so long that their tastes had become his.

“So I became a princess, wife of a prince of Kashmir,” she went on, her eyes smoldering with a marvelous shifting of clouds and colors. “I thought I knew the depths of men’s swinishness. I found I had much to learn. He was a beast. I fled from him into India, and the British protected me when his ruffians would have dragged me back to him. He still offers many thousand rupees to anyone who will bring me alive to him, so that he may soothe his vanity by having me tortured to death.”

“I have heard a rumor to that effect,” answered Gordon.

A recurrent thought caused his face to darken. He did not frown, but the effect was subtly sinister.

“That experience completed my distaste for the life I knew,” she said, her dark eyes vividly introspective. “I remembered that my father was a priest of Yolgan who fled away for love of a stranger woman. I had emptied the cup and the bowl was dry. I remembered Yolgan through the tales my father told me when I was a babe, and a great yearning rose in me to lose the world and find my soul. All the gods I knew had proved false to me. The mark of Erlik was upon me—” she parted her pearl-sewn vest and displayed a curious starlike mark between her firm breasts.

“I came to Yolgan as well you know, because you brought me, in the guise of a Kirghiz from Issik-kul. As you know, the people remembered my father, and though they looked on him as a traitor, they accepted me as one of them, and because of an old legend which spoke of the star on a woman’s bosom, they hailed me as a goddess, the incarnation of the daughter of Erlik Khan.

“For a while after you went away I was content. The people worshipped me with more sincerity than I had ever seen displayed by the masses of civilization. Their curious rituals were strange and fascinating. Then I began to go further into their mysteries; I began to sense the essence of the formula—” She paused, and Gordon saw the fear grow in her eyes again.

“I had dreamed of a calm retreat of mystics, inhabited by philosophers. I found a haunt of bestial devils, ignorant of all but evil. Mysticism? It is black shamanism, foul as the tundras which bred it. I have seen things that made me afraid. Yes, I, Yasmeena, who never knew the meaning of the word, I have learned fear. Yogok, the high priest, taught me. You warned me against Yogok before you left Yolgan. Well had I heeded you. He hates me. He knows I am not divine, but he fears my power over the people. He would have slain me long ago had he dared.

“I am wearied to death of Yolgan. Erlik Khan and his devils have proved no less an illusion than the gods of India and the West. I have not found the perfect way. I have found only awakened desire to return to the world I cast away.

“I want to go back to Delhi. At night I dream of the noise and smells of the streets and bazaars. I am half Indian, and all the blood of India is calling me. I was a fool. I had life in my hands and did not recognize it.”

“Why not go back, then?” asked Gordon.

She shuddered. “I cannot. The gods of Yolgan must remain in Yolgan forever. Should one depart, the people believe the city would perish. Yogok would be glad to see me go, but he fears the fury of the people too much either to slay me or aid me to escape. I knew there was but one man who might help me. I wrote a letter to you and smuggled it out by a Tajik trader. With it I sent my sacred emblem—a jeweled gold star— which would pass you safely through the country of the nomads. They would not harm a man bearing it. He would be safe from all but the priests of the city. I explained that in my letter.”

“I never got it,“ Gordon answered. “I’m here after a couple of scoundrels whom I was guiding into the Uzbek country, and who for no apparent reason murdered my servant Ahmed and deserted me in the hills. They’re in Yolgan now, somewhere.”

“White men?” she exclaimed. “That is impossible! They could never have got through the tribes—”

“There’s only one key to the puzzle,” he interrupted. “Somehow your letter fell into their hands. They used your star to let them through. They don’t mean to rescue you, because they got in touch with Yogok as soon as they reached the valley. There’s only one thing I can think of—they intend kidnapping you to sell to your former husband.”

She sat up straight; her white hands clenched on the edge of the divan and her eyes flashed. In that instant she looked as splendid and as dangerous as a cobra when it rears up to strike.

“Back to that pig? Where are these dogs? I will speak a word to the people and they shall cease to be!”

“That would betray yourself,” returned Gordon. “The people would kill the stranger, and Yogok, too, maybe, but they’d learn that you’d been trying to escape from Yolgan. They allow you the freedom of the temple, don’t they?”

“Yes; with shaven-headed skulkers spying on my every move, except when I am on this floor, from which only a single stair leads down. That stair is always guarded.”

“By a guard who sleeps,” said Gordon. “That’s bad enough, but if the people found you were trying to escape, they might shut you up in a little cell for the rest of your life. People are particularly careful of their deities.”

She shuddered, and her fine eyes flashed the fear an eagle feels for a cage. “Then what are we to do?”

“I don’t know—yet. I have nearly a hundred Turkoman ruffians hidden up in the hills, but just now they’re more hindrance than help. There’s not enough of them to do much good in a pitched battle, and they’re almost sure to be discovered tomorrow, if not before. I brought them into this mess, and it’s up to me to get them out—or as many as I can. I came here to kill these Englishmen, Ormond and Pembroke. But that can wait now. I’m going to get you out of here, but I don’t dare move until I know where Yogok and the Englishmen are. Is there anyone in Yolgan you can trust?”

“Any of the people would die for me, but they won’t let me go. Only actual harm done me by the monks would stir them up against Yogok. No; I dare trust none of them.”

“You say that stair is the only way up onto this floor?”

“Yes. The temple is built against the mountain, and galleries and corridors on the lower floors go back far into the mountain itself. But this is the highest floor, and is reserved entirely for me. There’s no escape from it except down through the temple, swarming with monks. I keep only one servant here at night, and she is at present sleeping in a chamber some distance from this and is senseless with bhang as usual.”

“Good enough!” grunted Gordon. “Here, take this pistol. Lock the door after I go through and admit no one but myself. You’ll recognize me by the nine raps, as usual.”

“Where are you going?” she demanded, staring up and mechanically taking the weapon he tendered her, butt first.

“To do a little spying,” he answered. “I’ve got to know what Yogok and the others are doing. If I tried to smuggle you out now, we might run square into them. I can’t make plans until I know some of theirs. If they intend sneaking you out tonight, as I think they do, it might be a good idea to let them do it, and then swoop down with the Turkomans and take you away from them, when they’ve got well away from the city. But I don’t want to do that unless I have to. Bound to be shooting and a chance of your getting hit by a stray bullet. I’m going now; listen for my rap.”

The mute guard still slumbered on the stair as Gordon glided past him. No lights glinted now as he descended into the lower corridor. He knew the cells were all empty, for the monks slept in chambers on a lower level. As he hesitated, he heard sandals shuffling down the passage in the pitch blackness.

Stepping into one of the cells he waited until the unseen traveler was opposite him, then he hissed softly. The tread halted and a voice muttered a query.

“Art thou Yatub?” asked Gordon in the gutturals of the Kirghiz. Many of the lower monks were pure Kirghiz in blood and speech.

“Nay,” came the answer. “I am Ojuh. Who art thou?”

“No matter; call me Yogok’s dog if thou wilt. I am a watcher. Have the white men come into the temple yet?”

“Aye. Yogok brought them by the secret way, lest the people suspect their presence. If thou art close to Yogok, tell me—what is his plan?”

“What is thine own opinion?” asked Gordon.

An evil laugh answered him, and he could feel the monk leaning closer in the darkness to rest an elbow on the jamb.