Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

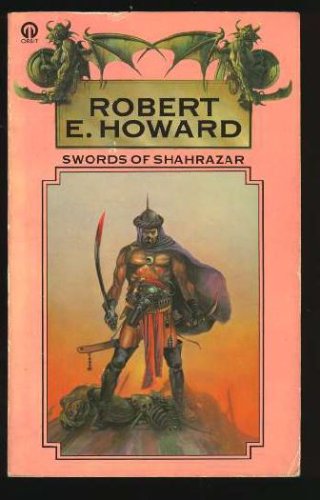

Published in Swords of Shahrazar, 1976.

L. Sprague DeCamp edited this into the Conan story “The Blood-Stained God” (first published 1955).

| Chapter I. In the Alley of Satan Chapter II. Paths of Suspicion |

Chapter III. Swords of the Crags Chapter IV. Toll of the God |

It was dark as the Pit in that evil-smelling Afghan alley down which Kirby O’Donnell, in his disguise of a swashbuckling Kurd, was groping, on a quest as blind as the darkness which surrounded him. It was a sharp, pain-edged cry smiting his ears that changed the whole course of events for him. Cries of agony were no uncommon sound in the twisting alleys of Medina el Harami, the City of Thieves, and no cautious or timid man would think of interfering in an affair which was none of his business. But O’Donnell was neither cautious nor timid, and something in his wayward Irish soul would not let him pass by a cry for help.

Obeying his instincts, he turned toward a beam of light that lanced the darkness close at hand, and an instant later was peering through a crack in the close-drawn shutters of a window in a thick stone wall. What he saw drove a red throb of rage through his brain, though years of adventuring in the raw lands of the world should have calloused him by this time. But O’Donnell could never grow callous to inhuman torture.

He was looking into a broad room, hung with velvet tapestries and littered with costly rugs and couches. About one of these couches a group of men clustered—seven brawny Yusufzai bravos, and two more who eluded identification. On that couch another man was stretched out, a Waziri tribesman, naked to the waist. He was a powerful man, but a ruffian as big and muscular as himself gripped each wrist and ankle. Between the four of them they had him spread-eagled on the couch, unable to move, though the muscles stood out in quivering knots on his limbs and shoulders. His eyes gleamed redly, and his broad breast glistened with sweat. There was a good reason. As O’Donnell looked, a supple man in a red silk turban lifted a glowing coal from a smoking brazier with a pair of silver tongs, and poised it over the quivering breast, already scarred from similar torture.

Another man, taller than the one with the red turban, snarled a question O’Donnell could not understand. The Waziri shook his head violently and spat savagely at the questioner. An instant later the red-hot coal dropped full on the hairy breast, wrenching an inhuman bellow from the sufferer. And, in that instant O’Donnell launched his full weight against the shutters.

The Irish-American was not a big man, but he was all steel and whalebone. The shutters splintered inward with a crash, and he hit the floor inside feet-first, scimitar in one hand and kindhjal in the other. The torturers whirled and yelped in astonishment.

They saw him as a masked, mysterious figure, for he was clad in the garments of a Kurd, with a fold of his flowing kafiyeh drawn about his face. Over his mask his eyes blazed like hot coals, paralyzing them. But only for an instant the scene held, frozen, and then melted into ferocious activity.

The man in the red turban snapped a quick word and a hairy giant lunged to meet the oncoming intruder. The Yusufzai held a three-foot Khyber knife low, and as he charged he ripped murderously upward. But the downward-lashing scimitar met the upward plunging wrist. The hand, still gripping the knife, flew from that wrist in a shower of blood, and the long, narrow blade in O’Donnell’s left hand sliced through the knifeman’s bull throat, choking the grunt of agony.

Over the crumpling corpse the American leaped at Red Turban and his tall companion. He did not fear the use of firearms. Shots ringing out by night in the Alley of Shaitan were sure to be investigated, and none of the inhabitants of the Alley desired official investigation.

He was right. Red Turban drew a knife, the tall man a sabre.

“Cut him down, Jallad!” snarled Red Turban, retreating before the American’s impetuous onslaught. “Achmet, help here!”

The man called Jallad, which means Executioner, parried O’Donnell’s slash and cut back. O’Donnell avoided the swipe with a shift that would have shamed the leap of a starving panther, and the same movement brought him within reach of Red Turban who was sneaking in with his knife. Red Turban yelped and leaped back, so narrowly avoiding O’Donnell’s kindhjal that the lean blade slit his silken vest and the skin beneath. He tripped over a stool and fell sprawling, but before O’Donnell could follow up his advantage, Jallad was towering over him, raining blows with his sabre. There was power as well as skill in the tall man’s arm, and for an instant O’Donnell was on the defensive.

But as he parried the lightning-like strokes, the American saw that the Yusufzai Red Turban had called Achmet was advancing, gripping an old Tower musket by the barrel. One smash of the heavy, brass-bound butt would crush a man’s head like an egg. Red Turban was scrambling to his feet, and in an instant O’Donnell would find himself hemmed in on three sides.

He did not wait to be surrounded. A flashing swipe of his scimitar, barely parried in time, drove Jallad back on his heels, and O’Donnell whirled like a startled cat and sprang at Achmet. The Yusufzai bellowed and lifted the musket, but the blinding swiftness of the attack had caught him off-guard. Before the blow could fall he was down, writhing in his own blood and entrails, his belly ripped wide open.

Jallad yelled savagely and rushed at O’Donnell, but the American did not await the attack.

There was no one between him and the Waziri on the couch. He leaped straight for the four men who still gripped the prisoner. They let go of the man, shouting with alarm, and drew their tulwars. One struck viciously at the Waziri, but the man rolled off the couch, evading the blow. The next instant O’Donnell was between him and them. They began hacking at the American, who retreated before them, snarling at the Waziri: “Get out! Ahead of me! Quick!”

“Dogs!” screamed Red Turban as he and Jallad rushed across the room. “Don’t let them escape!”

“Come and taste of death thyself, dog!” O’Donnell laughed wildly, above the clangor of steel. But even in the hot passion of battle he remembered to speak with a Kurdish accent.

The Waziri, weak and staggering from the torture he had undergone, slid back a bolt and threw open a door. It gave upon a small enclosed court.

“Go!” snapped O’Donnell. “Over the wall while I hold them back!”

He turned in the doorway, his blades twin tongues of death-edged steel. The Waziri ran stumblingly across the court and the men in the room flung themselves howling at O’Donnell. But in the narrow door their very numbers hindered them. He laughed and cursed them as he parried and thrust. Red Turban was dancing around behind the milling, swearing mob, calling down all the curses in his vocabulary on the thievish Kurd! Jallad was trying to get a clean swipe at O’Donnell, but his own men were in the way. Then O’Donnell’s scimitar licked out and under a flailing tulwar like the tongue of a cobra, and a Yusufzai, feeling chill steel in his vitals, shrieked and fell dying. Jallad, lunging with a full-arm reach, tripped over the writhing figure and fell. Instantly the door was jammed with squirming, cursing figures, and before they could untangle themselves, O’Donnell turned and ran swiftly across the yard toward the wall over which the Waziri had already disappeared.

O’Donnell leaped and caught the coping, swung himself up, and had one glimpse of a black, winding street outside. Then something smashed sickeningly against his head. It was a stool, snatched by Jallad and hurled with vindictive force as O’Donnell was momentarily outlined against the stars. But O’Donnell did not know what had hit him, for with the impact came oblivion. Limply and silently he toppled from the wall into the shadowy street below.

It was the tiny glow of a flashlight in his face that roused O’Donnell from his unconsciousness. He sat up, blinking, and cursed, groping for his sword. Then the light was snapped off and in the ensuing darkness a voice spoke: “Be at ease, Ali el Ghazi. I am your friend.”

“Who the devil are you?” demanded O’Donnell. He had found his scimitar lying on the ground near him, and now he stealthily gathered his legs under him for a sudden spring. He was in the street at the foot of the wall from which he had fallen, and the other man was but a dim bulk looming over him in the shadowy starlight.

“Your friend,” repeated the other. He spoke with a Persian accent. “One who knows the name you call yourself. Call me Hassan. It is as good a name as another.”

O’Donnell rose, scimitar in hand, and the Persian extended something toward him. O’Donnell caught the glint of steel in the starlight, but before he could strike as he intended, he saw that it was his own kindhjal Hassan had picked up from the ground and was offering him, hilt first.

“You are as suspicious as a starving wolf, Ali el Ghazi,” laughed Hassan. “But save your steel for your enemies.”

“Where are they?” demanded O’Donnell, taking the kindhjal.

“Gone. Into the mountains. On the trail of the blood-stained god.”

O’Donnell started violently. He caught the Persian’s khalat in an iron grip and glared fiercely into the man’s dark eyes, mocking and mysterious in the starlight.

“Damn you, what do you know of the blood-stained god?” His kindhjal’s sharp point just touched the Persian’s skin below his ribs.

“I know this,” said Hassan imperturbably. “I know you came to Medina el Harami following thieves who stole from you the map of a treasure greater than Akbar’s Hoard. I too came seeking something. I was hiding nearby, watching through a hole in the wall, when you burst into the room where the Waziri was being tortured. How did you know it was they who stole your map?”

“I didn’t!” muttered O’Donnell. “I heard the man cry out, and turned aside to stop the torture. If I’d known they were the men I was hunting—listen, how much do you know?”

“This much,” said Hassan. “In the mountains not far from this city, but hidden in an almost inaccessible place, there is an ancient heathen temple which the hill-people fear to enter. The region is forbidden to Ferengi, but one Englishman, named Pembroke, did find the temple, by accident, and entering it, found an idol crusted with red jewels, which he called the Blood-Stained God. He could not bring it away with him, but he made a map, intending to return. He got safely away, but was stabbed by a fanatic in Kabul and died there. But before he died he gave the map to a Kurd named Ali el Ghazi.”

“Well?” demanded O’Donnell grimly. The house behind him was dark and still. There was no other sound in the shadowy street except the whisper of the wind and the low murmur of their voices.

“The map was stolen,” said Hassan. “By whom, you know.”

“I didn’t know at the time,” growled O’Donnell. “Later I learned the thieves were an Englishman named Hawklin and a disinherited Afghan prince named Jehungir Khan. Some skulking servant spied on Pembroke as he lay dying, and told them. I didn’t know either of them by sight, but I managed to trace them to this city. Tonight I learned they were hiding somewhere in the Alley of Shaitan. I was blindly searching for a clue to their hiding place when I stumbled into that brawl.”

“You fought them without knowing they were the men you sought!” said Hassan. “The Waziri was one Yar Muhammad, a spy of Yakub Khan, the Jowaki outlaw chief. They recognized him, tricked him into their house and were burning him to make him tell them the secret trails through the mountains known only to Yakub’s spies. Then you came, and you know the rest.”

“All except what happened when I climbed the wall,” said O’Donnell.

“Somebody threw a stool,” replied Hassan. “When you fell beyond the wall they paid no more attention to you, either thinking you were dead, or not having recognized you because of your mask. They chased the Waziri, but whether they caught and killed him, or he got away, I don’t know. I do know that after a short chase they returned, saddled horses in great haste and set out westward, leaving the dead men where they fell. I came and uncovered your face, then, to see who you were, and recognized you.”

“Then the man in the red turban was Jehungir Khan,” muttered O’Donnell. “But where was Hawklin?”

“He was disguised as an Afghan—the man they called Jallad, the Executioner, because he has killed so many men.”

“I never dreamed ‘Jallad’ was a Ferengi,” growled O’Donnell.

“Not all men are what they seem,” said Hassan casually. “I happen to know, for instance, that you are no Kurd at all, but an American named Kirby O’Donnell.”

Silence held for a brief tick of time, in which life and death poised on a hair trigger.

“And what then?” O’Donnell’s voice was soft and deadly as a cobra’s hiss.

“Nothing! Like you I want the red god. That’s why I followed Hawklin here. But I can’t fight his gang alone. Neither can you. But we can join forces. Let us follow those thieves and take the idol away from them!”

“All right,” O’Donnell made a quick decision. “But I’ll kill you if you try any tricks, Hassan!”

“Trust me!” answered Hassan. “Come. I have horses at the serai—better than the steed which brought you into this city of thieves.”

The Persian led the way through narrow, twisting streets, overhung with latticed balconies, and along winding, ill-smelling alleys, until he stopped at the lamp-lit door of an enclosed courtyard. At his knock a bearded face appeared at the wicket, and following a few muttered words the gate swung open. Hassan entered confidently, and O’Donnell followed suspiciously. He half expected a trap of some sort; he had many enemies in Afghanistan, and Hassan was a stranger. But the horses were there, and a word from the keeper of the serai set sleepy servants to saddling them, and filling capacious saddle-pouches with packets of food. Hassan brought out a pair of high-powered rifles and a couple of well-filled cartridge belts.

A short time later they were riding together out of the west gate, perfunctority challenged by the sleepy guard. Men came and went at all hours in Medina el Harami. (It goes by another name on the maps, but men swear the ancient Moslem name fits it best.)

Hassan the Persian was portly but muscular, with a broad, shrewd face and dark, alert eyes. He handled his rifle expertly, and a scimitar hung from his hip. O’Donnell knew he would fight with cunning and courage when driven to bay. And he also knew just how far he could trust Hassan. The Persian adventurer would play fair just so long as the alliance was to his advantage. But if the occasion rose when he no longer needed O’Donnell’s help, he would not hesitate to murder his partner if he could, so as to have the entire treasure for himself. Men of Hassan’s type were as ruthless as a king cobra.

Hawklin was a cobra too, but O’Donnell did not shrink from the odds against them—five well-armed and desperate men. Wit and cold recklessness would even the odds when the time came.

Dawn found them riding through rugged defiles, with frowning slopes shouldering on either hand, and presently Hassan drew rein, at a loss. They had been following a well-beaten road, but now the marks of hoofs turned sharply aside and vanished on the bare rocky floor of a wide plateau.

“Here they left the road,” said Hassan. “Thus was Hawklin’s steed shod. But we cannot trace them over those bare rocks. You studied the map when you had it—how lies our route from here?”

O’Donnell shook his head, exasperated at this unexpected frustration.

“The map’s an enigma, and I didn’t have it long enough to puzzle it out. The main landmark, which locates an old trail that runs to the temple should be somewhere near this point. But it’s indicated on the map as ‘Akbar’s Castle’. I never heard of such a castle, or the ruins of any such castle—in these parts or anywhere else.”

“Look!” exclaimed Hassan, his eyes blazing, as he started up in his stirrups, and pointed toward a great bare crag that jutted against the skyline some miles to the west of them. “That is Akbar’s Castle! It is now called the Crag of Eagles, but in old times they called it Akbar’s Castle! I have read of it in an old, obscure manuscript! Somehow Pembroke knew that and called it by its old name to baffle meddlers! Come on! Jehungir Khan must have known that too. We’re only an hour behind them, and our horses are better than theirs.”

O’Donnell took the lead, cudgelling his memory to recall the details of the stolen map. Skirting the base of the crag to the southwest, he took an imaginary line from its summit to three peaks forming a triangle far to the south. Then he and Hassan rode westward in a slanting course. Where their course intersected the imaginary line, they came on the faint traces of an old trail, winding high up into the bare mountains. The map had not lied and O’Donnell’s memory had not failed them. The droppings of horses indicated that a party of riders had passed along the dim trail recently. Hassan asserted it was Hawklin’s party, and O’Donnell agreed.

“They set their course by Akbar’s Castle, just as we did. We’re closing the gap between us. But we don’t want to crowd them too close. They outnumber us. It’s up to us to stay out of sight until they get the idol. Then we ambush them and take it away from them.”

Hassan’s eyes gleamed; such strategy was joy to his Oriental nature.

“But we must be wary,” he said. “From here on the country is claimed by Yakub Khan, who robs all he catches. Had they known the hidden paths, they might have avoided him. Now they must trust to luck not to fall into his hands. And we must be alert, too! Yakub Khan is no friend of mine, and he hates Kurds!”

Mid-afternoon found them still following the dim path that meandered endlessly on—obviously the trace of an ancient, forgotten road.

“If that Waziri got back to Yakub Khan,” said Hassan, as they rode toward a narrow gorge that opened in the frowning slopes that rose about them, “the Jowakis will be unusually alert for strangers. Yar Muhammad didn’t suspect Hawklin’s real identity, though, and didn’t learn what he was after. Yakub won’t know, either. I believe he knows where the temple is, but he’s too superstitious to go near it. Afraid of ghosts. He doesn’t know about the idol. Pembroke was the only man who’d entered that temple in Allah only knows how many centuries. I heard the story from his servant in Peshawur who was dying from a snake bite. Hawklin, Jehungir Khan, you and I are the only men alive who know about the god—”

They reined up suddenly as a lean, hawk-faced Pathan rode out of the gorge mouth ahead of them.

“Halt!” he called imperiously, riding toward them with an empty hand lifted. “By what authority do you ride in the territory of Yakub Khan?”

“Careful,” muttered O’Donnell. “He’s a Jowaki. There may be a dozen rifles trained on us from those rocks right now.”

“I’ll give him money,” answered Hassan under his breath. “Yakub Khan claims the right to collect toll from all who travel through his country. Maybe that’s all this fellow wants.”

To the tribesmen he said, fumbling in his girdle; “We are but poor travellers, who are glad to pay the toll justly demanded by your brave chief. We ride alone.”

“Then who is that behind you?” harshly demanded the Jowaki, nodding his head in the direction from which they had come. Hassan, for all his wariness, half turned his head, his hand still outstretched with the coins. And in that instant fierce triumph flamed in the dark face of the Jowaki, and in one motion quick as the lunge of a cobra, he whipped a dagger from his girdle and struck at the unsuspecting Persian.

But quick as he was, O’Donnell was quicker, sensing the trap laid for them. As the dagger darted at Hassan’s throat, O’Donnell’s scimitar flashed in the sun and steel rang loud on steel. The dagger flew from the Pathan’s hand, and with a snarl he caught at the rifle butt which jutted from his saddle-scabbard. Before he could drag the gun free, O’Donnell struck again, cleaving the turban and the skull beneath. The Jowaki’s horse neighed and reared, throwing the corpse headlong, and O’Donnell wrenched his own steed around.

“Ride for the gorge!” he yelled. “It’s an ambush!”

The brief fight had occupied a mere matter of moments. Even as the Jowaki tumbled to the earth, rifle shots ripped out from the boulders on the slopes. Hassan’s horse leaped convulsively and bolted for the mouth of the defile, spattering blood at each stride. O’Donnell felt flying lead tug at his sleeve as he struck in the spurs and fled after the fleeing Persian who was unable to regain control of his pain-maddened beast.

As they swept toward the mouth of the gorge, three horsemen rode out to meet them, proven swordsmen of the Jowaki clan, swinging their broad-bladed tulwars. Hassan’s crazed mount was carrying him full into their teeth, and the Persian fought in vain to check him. Suddenly abandoning the effort he dragged his rifle from its boot and started firing pointblank as he came on. One of the oncoming horses stumbled and fell, throwing its rider. Another rider threw up his arms and toppled earthward. The third man hacked savagely at Hassan as the maddened horse raced past, but the Persian ducked beneath the sweeping blade and fled on into the gorge.

The next instant O’Donnell was even with the remaining swordsman, who spurred at him, swinging the heavy tulwar. The American threw up his scimitar and the blades met with a deafening crash as the horses came together breast to breast. The tribesman’s horse reeled to the impact, and O’Donnell rose in his stirrups and smiting downward with all his strength, beat down the lifted tulwar and split the skull of the wielder. An instant later the American was galloping on into the gorge. He half expected it to be full of armed warriors, but there was no other choice. Outside bullets were raining after him, splashing on rocks and ripping into stunted trees.

But evidently the man who set the trap had considered the marksmen hidden among the rocks on the slopes sufficient, and had posted only those four warriors in the gorge, for, as O’Donnell swept into it he saw only Hassan ahead of him. A few yards on the wounded horse stumbled and went down, and the Persian leaped clear as it fell.

“Get up behind me!” snapped O’Donnell, pulling up, and Hassan, rifle in hand, leaped up behind the saddle. A touch of the spurs and the heavily burdened horse set off down the gorge. Savage yells behind them indicated that the tribesmen outside were scampering to their horses, doubtless hidden behind the first ridge. They made a turn in the gorge and the noises became muffled. But they knew the wild hillmen would quickly be sweeping down the ravine after them, like wolves on the death-trail.

“That Waziri spy must have got back to Yakub Khan,” panted Hassan. “They want blood, not gold. Do you suppose they’ve wiped out Hawklin?”

“Hawklin might have passed down this gorge before the Jowakis came up to set their ambush,” answered O’Donnell. “Or the Jowakis might have been following him when they sighted us coming and set that trap for us. I’ve got an idea Hawklin is somewhere ahead of us.”

“No matter,” answered Hassan. “This horse won’t carry us far. He’s tiring fast. Their horses may be fresh. We’d better look for a place where we can turn and fight. If we can hold them off until dark maybe we can sneak away.”

They had covered perhaps another mile and already they heard faint sounds of pursuit, far behind them, when abruptly they came out into a broad bowl-like place, walled by sheer cliffs. From the midst of this bowl a gradual slope led up to a bottle-neck pass on the other side, the exit to this natural arena. Something unnatural about that bottle-neck struck O’Donnell, even as Hassan yelled and jumped down from the horse. A low stone wall closed the narrow gut of the pass. A rifle cracked from that wall just as O’Donnell’s horse threw up its head in alarm at the glint of the sun on the blue barrel. The bullet meant for the rider smashed into the horse’s head instead.

The beast lurched to a thundering fall, and O’Donnell jumped clear and rolled behind a cluster of rocks, where Hassan had already taken cover. Flashes of fire spat from the wall, and bullets whined off the boulders about them. They looked at each other with grim, sardonic humour.

“Well, we’ve found Hawklin!” said Hassan.

“And in a few minutes Yakub Khan will come up behind us and we’ll be between the devil and the deep blue sea!” O’Donnell laughed slightly, but their situation was desperate. With enemies blocking the way ahead of them and other enemies coming up the gorge behind them, they were trapped.

The boulders behind which they were crouching protected them from the fire from the wall, but would afford no protection from the Jowakis when they rode out of the gorge. If they changed their position they would be riddled by the men in front of them. If they did not change it, they would be shot down by the Jowakis behind them.

A voice shouted tauntingly: “Come out and get shot, you bloody bounder.” Hawklin was making no attempt to keep up the masquerade. “I know you, Hassan! Who’s that Kurd with, you? I thought I brained him last night!”

“Yes, a Kurd!” answered O’Donnell. “One called Ali el Ghazi!”

After a moment of astounded silence, Hawklin shouted: “I might have guessed it, you Yankee swine! Oh, I know who you are, all right! Well, it doesn’t matter now! We’ve got you where you can’t wriggle!”

“You’re in the same fix, Hawklin!” yelled O’Donnell. “You heard the shooting back down the gorge?”

“Sure. Who’s chasing you?”

“Yakub Khan and a hundred Jowakis!” O’Donnell purposely exaggerated. “When he’s wiped us out, do you think he’ll let you get away? After you tried to torture his secrets out of one of his men?”

“You’d better let us join you,” advised Hassan, recognizing, like O’Donnell, their one, desperate chance. “There’s a big fight coming and you’ll need all the help you can get if you expect to get out alive!”

Hawklin’s turbaned head appeared over the wall; he evidently trusted the honour of the men he hated, and did not fear a treacherous shot.

“Is that the truth?” he yelled.

“Don’t you hear the horses?” O’Donnell retorted.

No need to ask. The gorge reverberated with the thunder of hoofs and with wild yells. Hawklin paled. He knew what mercy he could expect from Yakub Khan. And he knew the fighting ability of the two adventurers—knew how heavily their aid would count in a fight to the death.

“Get in, quick!” he shouted. “If we’re still alive when the fight’s over we’ll decide who gets the idol then!”

Truly it was no time to think of treasure, even of the Crimson God! Life itself was at stake. O’Donnell and Hassan leaped up, rifles in hand, and sprinted up the slope toward the wall. Just as they reached it the first horsemen burst out of the gorge and began firing. Crouching behind the wall, Hawklin and his men returned the fire. Half a dozen saddles were emptied and the Jowakis, demoralized by the unexpectedness of the volley, wheeled and fled back into the gorge.

O’Donnell glanced at the men Fate had made his allies—the thieves who had stolen his treasure-map and would gladly have killed him fifteen minutes before; Hawklin, grim and hard-eyed in his Afghan guise, Jehungir Khan, dapper even after leagues of riding, and three hairy Yusufzai swashbucklers, addressed variously as Akbar, Suliman and Yusuf. These bared their teeth at him. This was an alliance of wolves, which would last only so long as the common menace lasted.

The men behind the wall began sniping at white-clad figures flitting among the rocks and bushes near the mouth of the gorge. The Jowakis had dismounted and were crawling into the bowl, taking advantage of every bit of cover. Their rifles cracked from behind every boulder and stunted tamarisk.

“They must have been following us,” snarled Hawklin, squinting along his rifle barrel. “O’Donnell, you lied! There can’t be a hundred men out there.”

“Enough to cut our throats, anyway,” retorted O’Donnell, pressing his trigger. A man darting toward a rock yelped and crumpled, and a yell of rage went up from the lurking warriors. “Anyway, there’s nothing to keep Yakub Khan from sending for reinforcements. His village isn’t many hours’ride from here.”

Their conversation was punctuated by the steady cracking of the rifle. The Jowakis, well hidden, were suffering little from the exchange.

“We’ve a sporting chance behind this wall,” growled Hawklin. “No telling how many centuries it’s stood here. I believe it was built by the same race that built the Red God’s temple. You’ll find ruins like this all through these hills. Damn!” He yelled at his men: “Hold your fire! Our ammunitions’s getting low. They’re working in close for a rush. Save your cartridges for it. We’ll mow ’em down when they get into the open.” An instant later he shouted: “Here they come!”

The Jowakis were advancing on foot, flitting from rock to rock, from bush to stunted bush, firing as they came. The defenders grimly held their fire, crouching low and peering through the shallow crenelations. Lead flattened against the stone, knocking off chips and dust. Suliman swore luridly as a slug ripped into his shoulder. Back in the gorge-mouth O’Donnell glimpsed Yakub Khan’s red beard, but the chief took cover before he could draw a bead. Wary as a fox, Yakub was not leading the charge in person.

But his clansmen fought with untamed ferocity. Perhaps the silence of the defenders fooled them into thinking their ammunition was exhausted. Perhaps the blood-lust that burned in their veins overcame their cunning. At any rate they broke cover suddenly, thirty-five or forty of them, and rushed up the slope with the rising ululation of a wolf-pack. Point-blank they fired their rifles and then lunged at the barrier with three-foot knives in their hands.

“Now!” screamed Hawklin, and a close-range volley raked the oncoming horde. In an instant the slope was littered with writhing figures. The men behind that wall were veteran fighters, to a man, who could not miss at that range. The toll taken by their sweeping hail of lead was appalling but the survivors came on, eyes glaring, foam on their beards, blades glittering in hairy fists.

“Bullets won’t stop ’em!” yelled Hawklin, livid, as he fired his last rifle cartridge. “Hold the wall or we’re all dead men!”

The defenders emptied their guns into the thick of the mass and then rose up behind the wall, drawing steel or clubbing rifles. Hawklin’s strategy had failed, and now it was hand-to-hand, touch and go, and the devil take the unlucky.

Men stumbled and went down beneath the slash of the last bullets, but over their writhing bodies the horde rolled against the wall and locked there. All up and down the barrier sounded the smash of bone-splintering blows, the rasp and slither of steel meeting steel, the gasping oaths of dying men. The handful of defenders still had the advantage of position, and dead men lay thick at the foot of the wall before the Jowakis got a foothold on the barricade. A wild-eyed tribesman jammed the muzzle of an ancient musket full in Akbar’s face, and the discharge all but blew off the Yusufzai’s head. Into the gap left by the falling body the howling Jowaki lunged, hurling himself up and over the wall before O’Donnell could reach the spot. The American had stepped back, fumbling to reload his rifle, only to find his belt empty. Just then he saw the raving Jowaki come over the wall. He ran at the man, clubbing his rifle, just as the Pathan dropped his empty musket and drew a long knife. Even as it cleared the scabbard O’Donnell’s rifle butt crushed his skull.

O’Donnell sprang over the falling corpse to meet the men swarming on to the wall. Swinging his rifle like a flail, he had no time to see how the fight was going on either side of him. Hawklin was swearing in English, Hassan in Persian, and somebody was screaming in mortal agony. He heard the sound of blows, gasps, curses, but he could not spare a glance to right or left. Three blood-mad tribesmen were fighting like wildcats for a foothold on the wall. He beat at them until his rifle stock was a splintered fragment, and two of them were down with broken heads, but the other, straddling the wall, grabbed the American with gorilla-like hands and dragged him into quarters too close to use his bludgeon. Half throttled by those hairy fingers, on his throat, O’Donnell dragged out his kindhjal and stabbed blindly, again and again, until blood gushed over his hand, and with a moaning cry the Jowaki released him and toppled from the wall.

Gasping for air, O’Donnell looked about him, realizing the pressure had slackened. No longer was the barrier massed with wild faces. The Jowakis were staggering down the slope—the few left to flee. Their losses had been terrible, and not a man of those who retreated but streamed blood from some wound.

But the victory had been costly. Suliman lay limply across the wall, his head smashed like an egg. Akbar was dead. Yusuf was dying, with a stab-wound in the belly, and his screams were terrible. As O’Donnell looked he saw Hawklin ruthlessly end his agony with a pistol bullet through the head. Then the American saw Jehungir Khan, sitting with his back against the wall, his hands pressed to his body, while blood seeped steadily between his fingers. The prince’s lips were blue, but he achieved a ghastly smile.

“Born in a palace,” he whispered. “And I’m dying behind a rock wall! No matter—it is Kismet. There is a curse on heathen treasure—men have always died when they rode the trail of the Blood-Stained God—” And he died as he spoke.

Hawklin, O’Donnell and Hassan glanced silently at each other. They were the only survivors—three grim figures, blackened with powder-smoke, splashed with blood, their garments tattered. The fleeing Jowakis had vanished in the gorge, leaving the canyon-bowl empty except for the dead men on the slope.

“Yakub got away!” Hawklin snarled. “I saw him sneaking off when they broke. He’ll make for his village—get the whole tribe on our trail! Come on! We can find the temple. Let’s make a race of it—take the chance of getting the idol and then making our way out of the mountains somehow, before he catches us. We’re in this jam together. We might as well forget what’s passed and join forces for good. There’s enough treasure for the three of us.”

“There’s truth in what you say,” growled O’Donnell. “But you hand over that map before we start.”

Hawklin still held a smoking pistol in his hand, but before he could lift it Hassan covered him with a revolver.

“I saved a few cartridges for this,” said the Persian, and Hawklin saw the blue noses of the bullets in the chambers. “Give me that gun. Now give the map to O’Donnell.”

Hawklin shrugged his shoulders and produced the crumpled parchment. “Damn you, I cut a third of that treasure, if we get it!” he snarled.

O’Donnell glanced at it and thrust it into his girdle.

“All right. I don’t hold grudges. You’re a swine, but if you play square with us, we’ll treat you as an equal partner, eh, Hassan?”

The Persian nodded, thrusting both guns into his girdle. “This is no time to quibble. It will take the best efforts of all three of us if we get out of this alive. Hawklin, if the Jowakis catch up with us I’ll give you your pistol. If they don’t you won’t need it.”

There were horses tied in the narrow pass behind the wall. The three men mounted the best beasts, turned the others loose and rode up the canyon that wound away and away beyond the pass. Night fell as they travelled, but through the darkness they pushed recklessly on. Somewhere behind them, how far or how near they could not know, rode the tribesmen of Yakub Khan, and if the chief caught them his vengeance would be ghastly. So through the blackness of the nighted Himalayas they rode, three desperate men on a mad quest, with death on their trail, unknown perils ahead of them, and suspicion of each other edging their nerves.

O’Donnell watched Hassan like a hawk. Search of the bodies at the wall had failed to reveal a single unfired cartridge, so Hassan’s pistols were the only firearms left in the party. That gave the Persian an advantage O’Donnell did not relish. If the time came when Hassan no longer needed the aid of his companions, O’Donnell believed the Persian would not scruple to shoot them both down in cold blood. But he would not turn on them as long as he needed their assistance, and when it came to a fight—O’Donnell grimly fingered his blades. More than once he had matched them against hot lead, and lived.

As they groped their way by the starlight, guided by the map which indicated landmarks unmistakable, even by night, O’Donnell found himself wondering again what it was that the maker of that map had tried to tell him, just before he died. Death had come to Pembroke quicker than he had expected. In the very midst of a description of the temple, blood had gushed to his lips and he had sunk back, desperately fighting to gasp a few more words even as he died. It sounded like a warning—but of what?

Dawn was breaking as they came out of narrow gorge into a deep, high-walled valley. The defile through which they entered, a narrow alley between towering cliffs, was the only entrance; without the map they would never have found it. It came out upon a ledge which ran along the valley wall, a jutting shelf a hundred feet wide with the cliff rising three hundred feet above it on one hand, and falling away to a thousand foot drop on the other. There seemed no way down into the mist-veiled depths of the valley, far below. But they wasted few glances on what lay below them, for what they saw ahead of them drove hunger and fatigue from their minds. There on the ledge stood the temple, gleaming in the rising sun. It was carved out of the sheer rock of the cliff, its great portico facing them. The ledge was like a pathway to its dully-glinting door:

What race, what culture it represented, O’Donnell did not try to guess. A thousand unknown conquerors had swept over these hills before the grey dawn of history. Nameless civilizations had risen and crumbled before the peaks shook to the trumpets of Alexander.

“How will we open the door?” O’Donnell wondered. The great bronze portal looked as though it were built to withstand artillery. He unfolded the map and glanced again at the notes scrawled on the margins. But Hassan slipped from his saddle and ran ahead of them, crying out in his greed. A strange frenzy akin to madness had seized the Persian at the sight of the temple, and the thought of the fabulous wealth that lay within.

“He’s a fool!” grunted Hawklin, swinging down from his horse. “Pembroke left a warning scribbled on the margin of that map—‘The temple can be entered, but be careful, for the god will take his toll.’ ”

Hassan was tugging and pulling at various ornaments and projections on the portal. They heard him cry out exultantly as it moved under his hands—then his cry changed to a scream of terror as the door, a ton of carved bronze, swayed outward and fell crashing. The Persian had no time to avoid it. It crushed him like an ant. He was completely hidden under the great metal slab from beneath which oozed streams of crimson.

Hawklin shrugged his shoulders.

“I said he was a fool. The ancients knew how to guard their treasure. I wonder how Pembroke escaped being smashed.”

“He evidently stumbled on some way to swing the door open without releasing it from its hinges,” answered O’Donnell. “That’s what happened when Hassan jerked on those knobs. That must have been what Pembroke was trying to tell me when he died—which knobs to pull and which to let alone.”

“Well, the god has his toll, and the way’s clear for us,” grunted Hawklin, callously striding past the encrimsoned door. O’Donnell was close on his heels. Both men paused on the broad threshold, peering into the shadowy interior much as they might have peered into the lair of a serpent. But no sudden doom descended on them, no shape of menace rose before them. They entered cautiously. Silence held the ancient temple, broken only by the soft scuff of their boots.

They blinked in the semi-gloom; out of it a blaze of crimson like a lurid glow of sunset smote their eyes. They saw the blood-stained god, a thing of brass, crusted with flaming gems. It was in the shape of a dwarfish man, and it stood upright on its great splay feet on a block of basalt, facing the door. To the left of it, a few feet from the base of the pedestal, the floor of the temple was cleft from wall to wall by a chasm some fifteen feet wide. At some time or other an earthquake had split the rock, and there was no telling how far it descended into echoing depths. Into that black abyss, ages ago, doubtless screaming victims had been hurled by hideous priests as human sacrifices to the Crimson God. The walls of the temple were lofty and fantastically carved, the roof dim and shadowy above them.

But the attention of the men was fixed avidly on the idol. It was brutish, repellent, a leprous monstrosity, whose red jewels gave it a repellently blood-splashed appearance. But it represented a wealth that made their brains swim.

“God!” breathed O’Donnell. “Those gems are real! They’re worth a fortune!”

“Millions!” panted Hawklin. “Too much to share with a damned Yankee!”

It was those words, breathed unconsciously between the Englishman’s clenched teeth, which saved O’Donnell’s life, dazzled as he was by the blaze of that unholy idol. He wheeled, caught the glint of Hawklin’s sabre, and ducked just in time. The whistling blade sliced a fold from his head-dress. Cursing his carelessness—for he might have expected treachery—he leaped back, whipping out his scimitar.

The tall Englishman came in a rush, and O’Donnell met him, close-pent rage loosing itself in a gust of passion. Back and forth they fought, up and down before the leering idol, feet scuffing swiftly on the rock, blades rasping, slithering and ringing, blue sparks showering as they moved through patches of shadow.

Hawklin was taller than O’Donnell, longer of arm, but O’Donnell was equally strong, and a blinding shade quicker on his feet. Hawklin feared the naked kindhjal in his left hand more than he did the scimitar, and he endeavored to keep the fighting at long range, where his superior reach would count heavily. He gripped a dagger in his own left hand, but he knew he could not compete with O’Donnell in knife-play.

But he was full of deadly tricks with the longer steel. Again and again O’Donnell dodged death by the thickness of a hair, and so far his own skill and speed had not availed to break through the Englishman’s superb guard.

O’Donnell sought in vain to work into close quarters. Once Hawklin tried to rush him over the lip of the chasm, but nearly impaled himself on the American’s scimitar and abandoned the attempt.

Then suddenly, unexpectedly, the end came. O’Donnell’s foot slipped slightly on the smooth floor, and his blade wavered for an instant. Hawklin threw all his strength and speed behind a lunging thrust that would have driven his saber clear through O’Donnell’s body had it reached its mark. But the American was not as much off-balance as Hawklin thought. A twist of his supple body, and the long lean blade passed beneath his right arm-pit, ploughing through the loose khalat as it grazed his ribs. For an instant the blade was caught in the folds of the loose cloth, and Hawklin yelled wildly and stabbed with his dagger. It sank deep in O’Donnell’s right arm as he lifted it, and simultaneously the kindhjal in O’Donnell’s left hand plunged between Hawklin’s ribs.

The Englishman’s scream broke in a ghastly gurgle. He reeled back, and as O’Donnell tore out the blade, blood spurted and Hawklin fell limply, dead before he hit the floor.

O’Donnell dropped his weapon and knelt, ripping a strip of cloth from his khalat for a bandage. His wounded arm was bleeding freely, but a quick investigation assured him that the dagger had not severed any important muscle or vein.

As he bound it up, tying knots with his fingers and teeth, he glanced at the Blood-Stained God which leered down on him and the man he had just slain. It had taken full toll, and it seemed to gloat, with its carven, gargoyle face. He shivered. Surely it must be accursed. Could wealth gained from such a source, and at such a price as the dead man at his feet, ever bring luck? He put the thought from him. The Red God was his, bought by sweat and blood and sword-strokes. He must pack it on a horse and be gone before the vengeance of Yakub Khan overtook him. He could not go back the way he had come. The Jowakis barred that way. He must strike out blindly, through unfamiliar mountains, trusting to luck to make his way to safety.

“Put up your hands!” It was a triumphant shout that rang to the roof.

In one motion he was on his feet, facing the door—then he froze.

Two men stood before him, and one covered him with a cocked rifle. The man was tall, lean and red-bearded.

“Yakub Khan!” ejaculated O’Donnell.

The other man was a powerful fellow who seemed vaguely familiar.

“Drop your weapons!” The chief laughed harshly. “You thought I had run away to my village, did you not? Fool! I sent all my men but one, who was the only one not wounded, to rouse the tribe, while with this man I followed you. I have hung on your trail all night, and I stole in here while you fought with that one on the floor there. Your time has come, you Kurdish dog! Back! Back! Back!”

Under the threat of the rifle O’Donnell moved slowly backward until he stood close to the black chasm. Yakub followed him at a distance of a few feet, the rifle muzzle never wavering.

“You have led me to treasure,” murmured Yakub, squinting down the blue barrel in the dim light. “I did not know this temple held such an idol! Had I known, I would have looted it long ago, in spite of the superstition of my followers. Yar Muhammad, pick up his sword and dagger.”

At the name the identity of Yakub’s powerful follower became clear. The man stooped and picked up the sword, then exclaimed: “Allah!”

He was staring at the brazen hawk’s head that formed the pommel of O’Donnell’s scimitar.

“Wait!” the Waziri cried. “This is the sword of him who saved me from torture, at the risk of his own life! His face was covered, but I remember the hawk-head on his hilt! This is that Kurd!”

“Be silent!” snarled the chief. “He is a thief and he dies!”

“Nay!” The Waziri was galvanized with the swift, passionate loyalty of the hillman. “He saved my life! Mine, a stranger! What have you ever given me but hard tasks and scanty pay? I renounce my allegiance, you Jowaki thief!”

“Dog!” roared the chief, whirling on Yar Muhammad, who sprang back, being without a gun. Yakub Khan fired from the hip and the bullet sheared a tuft from the Waziri’s beard. Yar Muhammad yelled a curse and ran behind the idol’s pedestal.

At the crack of the shot O’Donnell was leaping to grapple with the chief, but even as he sprang he saw he would fail. With a snarl Yakub turned the rifle on him, and that fleeting instant O’Donnell knew death would spit from that muzzle before he could reach the Jowaki. Yakub’s finger hooked the trigger—and then Yar Muhammad hurled the idol. His mighty muscles creaked as he threw it.

Full against the Jowaki it crashed, bearing him backward—over the lip of the chasm! He fired wildly as he fell, and O’Donnell felt the wind of the bullet. One frenzied shriek rang to the roof as idol and man vanished together.

Stunned, O’Donnell sprang forward and gazed down into the black depths. He looked and listened long, but no sound of their fall ever welled up to him. He shuddered at the realization of that awful depth, and drew back quickly. A hard hand on his shoulder brought him around to look into the grinning, bearded countenance of Yar Muhammad.

“Thou art my comrade henceforth,” said the Waziri. “If thou art he who calls himself Ali el Ghazi, is it true that a Ferengi lurks beneath those garments?”

O’Donnell nodded, watching the man narrowly.

Yar Muhammad but grinned the more widely.

“No matter! I have slain the chief I followed, and the hands of his tribe will be lifted against me. I must follow another chief—and I have heard many tales of the deeds of Ali el Ghazi! Wilt thou accept me as thy follower, sahib?”

“Thou art a man after mine own heart,” said O’Donnell, extending his hand, white man fashion.

“Allah favour thee!” Yar Muhammad exclaimed joyously, returning the strong grip. “And now let us go swiftly! The Jowakis will be here before many hours have passed, and they must not find us here! But there is a secret path beyond this temple which leads down into the valley, and I know hidden trails that will take us out of the valley and far beyond their reach before they can get here. Come!”

O’Donnell took up his weapons and followed the Waziri out of the temple. The idol was gone forever, but it had been the price of his life. And there were other lost treasures that challenged a restless adventurer. Already his mind was flying ahead to the search of hidden, golden hoards celebrated in a hundred other legends. . . .

“Alhamdolillah!” he said, and laughed with the sheer joy of living as he followed the Waziri to the place where they had left the tethered horses.