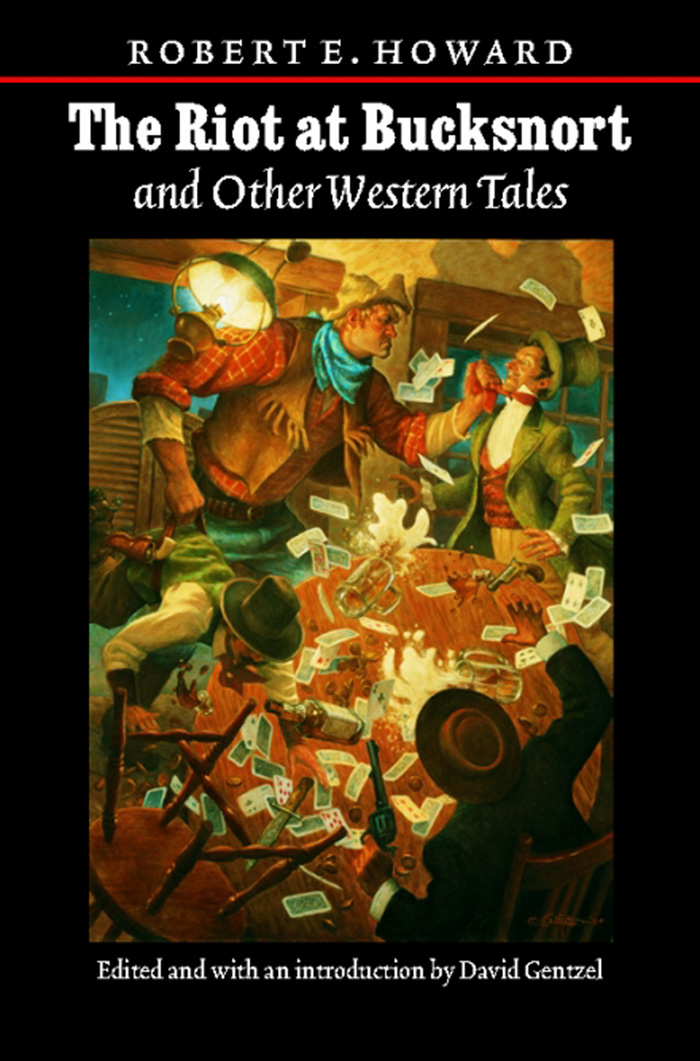

Cover from the collection The Riot at Bucksnort and Other Western Tales (2005).

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

Published in Action Stories, Vol. 13, No. 3 (August 1935), heavily rewritten and retitled.

The original version published in Mayhem on Bear Creek, 1979.

| “Cupid from Bear Creek” (1935) | “The Peaceful Pilgrim” (1968) |

Some day, maybe, when I’m a old man, I’ll have sense enough to stay away from these new mining camps which springs up overnight like mushroomers. There was that time in Teton Gulch, for instance. It was a ill-advised moment when I stopped there on my way back to the Humbolts from the Yavapai country. I was a sheep for the shearing and I was shorn plenty. And if some of the shearers got fatally hurt in the process, they needn’t to blame me. I was acting in self-defense all the way through.

At first I aimed to pass right through Teton Gulch without stopping. I was in a hurry to git back to my home-country and find out was any misguided idjits trying to court Dolly Rixby, the belle of War Paint, in my absence. I hadn’t heard from her since I left Bear Creek, five weeks before, which warn’t surprizing, seeing as how she couldn’t write, nor none of her family, and I couldn’t of read it if they had. But they was a lot of young bucks around War Paint which could be counted on to start shining around her the minute my back was turnt.

But my thirst got the best of me, and I stopped in the camp. I was drinking me a dram at the bar of the Yaller Dawg Saloon and Hotel, when the bar-keep says, after studying me a spell, he says: “You must be Breckinridge Elkins, of Bear Creek.”

I give the matter due consideration, and ’lowed as how I was.

“How come you knowed me?” I inquired suspiciously, because I hadn’t never been in Teton Gulch before, and he says: “Well, I’ve heard tell of Breckinridge Elkins, and when I seen you, I figgered you must be him, because I don’t see how they can be two men in the world that big. By the way, there’s a friend of yore’n upstairs—Blink Wiltshaw, from War Paint. I’ve heered him brag about knowin’ you personal. He’s upstairs now, fourth door from the stair-head, on the left.”

Now that there news interested me, because Blink was the most persistent of all them young mavericks which was trying to spark Dolly Rixby. Just the night before I left for Yavapai, I catched him coming out of her house, and was fixing to sweep the street with him when Dolly come out and stopped me and made us shake hands.

It suited me fine for him to be in Teton Gulch, or anywheres just so he warn’t no-wheres nigh Dolly Rixby, so I thought I’d pass the time of day with him.

I went upstairs and knocked on the door, and bam! went a gun inside and a .45 slug ripped through the door and taken a nick out of my off-ear. Getting shot in the ear always did irritate me, so without waiting for no more exhibitions of hospitality, I give voice to my displeasure in a deafening beller and knocked the door off its hinges and busted into the room over its ruins.

For a second I didn’t see nobody, but then I heard a kind of gurgle going on, and happened to remember that the door seemed kind of squishy underfoot when I tromped over it, so I knowed that whoever was in the room had got pinned under the door when I knocked it down.

So I reached under it and got him by the collar and hauled him out, and shore enough it was Blink Wiltshaw. He was limp as a lariat, and glassy-eyed and pale, and was still kind of trying to shoot me with his six-shooter when I taken it away from him.

“What the hell’s the matter with you?” I demanded sternly, dangling him by the collar with one hand, whilst shaking him till his teeth rattled. “Didn’t Dolly make us shake hands? What you mean by tryin’ to ’sasserinate me through a hotel door?”

“Lemme down, Breck,” he gasped. “I didn’t know it was you. I thought it was Rattlesnake Harrison comin’ after my gold.”

So I sot him down. He grabbed a jug of licker and taken a swig, and his hand shook so he spilled half of it down his neck.

“Well?” I demanded. “Ain’t you goin’ to offer me a snort, dern it?”

“Excuse me, Breckinridge,” he apolergized. “I’m so derned jumpy I dunno what I’m doin’. You see them buckskin pokes?” says he, p’inting at some bags on the bed. “Them is plumb full of nuggets. I been minin’ up the Gulch, and I hit a regular bonanza the first week. But it ain’t doin’ me no good.”

“What you mean?” I demanded.

“These mountains is full of outlaws,” says he. “They robs, and murders every man which makes a strike. The stagecoach has been stuck up so often nobody sends their dust out on it no more. When a man makes a pile he sneaks out through the mountains at night, with his gold on pack-mules. I aimed to do that last night. But them outlaws has got spies all over the camp, and I know they got me spotted. Rattlesnake Harrison’s their chief, and he’s a ring-tailed he-devil. I been squattin’ over this here gold with my pistol in fear and tremblin’, expectin’ ’em to come right into camp after me. I’m dern nigh loco!”

And he shivered and cussed kind of whimpery, and taken another dram, and cocked his pistol and sot there shaking like he’d saw a ghost or two.

“You got to help me, Breckinridge,” he said desperately. “You take this here gold out for me, willya? The outlaws don’t know you. You could hit the old Injun path south of the camp and foller it to Hell-Wind Pass. The Chawed-Ear—Wahpeton stage goes through there about sun-down. You could put the gold on the stage there, and they’d take it on to Wahpeton. Harrison wouldn’t never think of holdin’ it up after it left Hell-Wind. They always holds it up this side of the Pass.”

“What I want to risk my neck for you for?” I demanded bitterly, memories of Dolly Rixby rising up before me. “If you ain’t got the guts to tote out yore own gold—”

“T’ain’t altogether the gold, Breck,” says he. “I’m tryin’ to git married, and—”

“Married?” says I. “Here? In Teton Gulch? To a gal in Teton Gulch?”

“Married to a gal in Teton Gulch,” he avowed. “I was aimin’ to git hitched tomorrer, but they ain’t a preacher or justice of the peace in camp to tie the knot. But her uncle the Reverant Rembrandt Brockton is a circuit rider, and he’s due to pass through Hell-Wind on his way to Wahpeton today. I was aimin’ to sneak out last night, hide in the hills till the stage come through, then put the gold on the stage and bring Brother Rembrandt back with me. But yesterday I learnt Harrison’s spies was watchin’ me, and I’m scairt to go. Now Brother Rembrandt will go on to Wahpeton, not knowin’ he’s needed here, and no tellin’ when I’ll be able to git married—”

“Hold on,” I said hurried, doing some quick thinking. I didn’t want this here wedding to fall through. The more Blink was married to some gal in Teton, the less he could marry Dolly Rixby.

“Blink,” I said, grasping his hand warmly, “let it never be said that a Elkins ever turned down a friend in distress. I’ll take yore gold to Hell-Wind Pass and bring back Brother Rembrandt.”

Blink fell onto my neck and wept with joy. “I’ll never forgit this, Breckinridge,” says he, “and I bet you won’t neither! My hoss and pack-mule are in the stables behind the saloon.”

“I don’t need no pack-mule,” I says. “Cap’n Kidd can pack the dust easy.”

Cap’n Kidd was getting fed out in the corral next to the hotel. I went out there and got my saddle-bags, which is a lot bigger’n most saddle-bags, because all my plunder has to be made to fit my size. They’re made outa three-ply elkskin, stitched with rawhide thongs, and a wildcat couldn’t claw his way out of ’em.

I noticed quite a bunch of men standing around the corral looking at Cap’n Kidd, but thought nothing of it, because he is a hoss which naturally attracts attention. But whilst I was getting my saddle-bags, a long lanky cuss with long yaller whiskers come up and said, says he: “Is that yore hoss in the corral?”

“If he ain’t he ain’t nobody’s,” I says.

“Well, he looks a whole lot like a hoss that was stole off my ranch six months ago,” he said, and I seen ten or fifteen hard-looking hombres gathering around me. I laid down my saddle-bags sudden-like and reached for my guns, when it occurred to me that if I had a fight there I might git arrested and it would interfere with me bringing Brother Rembrandt in for the wedding.

“If that there is yore hoss,” I said, “you ought to be able to lead him out of that there corral.”

“Shore I can,” he says with a oath. “And what’s more, I aim’ta.”

He looked at me suspiciously, but he taken up a rope and clumb the fence and started toward Cap’n Kidd which was chawing on a block of hay in the middle of the corral. Cap’n Kidd throwed up his head and laid back his ears and showed his teeth, and Jake stopped sudden and turned pale.

“I—I don’t believe that there is my hoss, after all!” says he.

“Put that lasso on him!” I roared, pulling my right-hand gun. “You say he’s yore’n; I say he’s mine. One of us is a liar and a hoss-thief, and I aim to prove which. Gwan, before I festoons yore system with lead polka-dots!”

He looked at me and he looked at Cap’n Kidd, and he turned bright green all over. He looked agen at my .45 which I now had cocked and p’inted at his long neck, which his adam’s apple was going up and down like a monkey on a pole, and he begun to aidge toward Cap’n Kidd again, holding the rope behind him and sticking out one hand.

“Whoa, boy,” he says kind of shudderingly. “Whoa—good old feller—nice hossie—whoa, boy—ow!”

He let out a awful howl as Cap’n Kidd made a snap and bit a chunk out of his hide. He turned to run but Cap’n Kidd wheeled and let fly both heels which caught Jake in the seat of the britches, and his shriek of despair was horrible to hear as he went head-first through the corral fence into a hoss-trough on the other side. From this he ariz dripping water, blood and profanity, and he shook a quivering fist at me and croaked: “You derned murderer! I’ll have yore life for this!”

“I don’t hold no conversation with hoss-thieves,” I snorted, and picked up my saddle-bags and stalked through the crowd which give back in a hurry.

I taken the saddle-bags up to Blink’s room, and told him about Jake, thinking he’d be amoosed, but got a case of aggers again, and said: “That was one of Harrison’s men! He meant to take yore hoss. It’s a old trick, and honest folks don’t dare interfere. Now they got you spotted! What’ll you do?”

“Time, tide and a Elkins waits for no man!” I snorted, dumping the gold into the saddle-bags. “If that yaller-whiskered coyote wants any trouble, he can git a bellyfull. Don’t worry, yore gold will be safe in my saddle-bags. It’s as good as in the Wahpeton stage right now. And by midnight I’ll be back with Brother Rembrandt Brockton to hitch you up with his niece.”

“Don’t yell so loud,” begged Blink. “The cussed camp’s full of spies. Some of ’em may be downstairs now, listenin’.”

“I warn’t speakin’ above a whisper,” I said indignantly.

“That bull’s beller may pass for a whisper on Bear Creek,” says he, wiping off the sweat, “but I bet they can hear it from one end of the Gulch to the other, at least.”

It’s a pitable sight to see a man with a case of the scairts; I shook hands with him and left him pouring red licker down his gullet like it was water, and I swung the saddle-bags over my shoulder and went downstairs, and the bar-keep leaned over the bar and whispered to me: “Look out for Jake Roman! He was in here a minute ago, lookin’ for trouble. He pulled out just before you come down, but he won’t be forgittin’ what yore hoss done to him!”

“Not when he tries to set down, he won’t,” I agreed, and went on out to the corral, and they was a crowd of men watching Cap’n Kidd eat his hay, and one of ’em seen me and hollered: “Hey, boys, here comes the giant! He’s goin’ to saddle that man-eatin’ monster! Hey, Bill! Tell the boys at the bar!”

And here come a whole passel of fellers running out of all the saloons, and they lined the corral fence solid, and started laying bets whether I’d git the saddle on Cap’n Kidd or git my brains kicked out. I thought miners must all be crazy. They ought’ve knowed I was able to saddle my own hoss.

Well, I saddled him and throwed on the saddle-bags and clumb aboard, and he pitched about ten jumps like he always does when I first fork him—t’warn’t nothing, but them miners hollered like wild Injuns. And when he accidentally bucked hisself and me through the fence and knocked down a section of it along with fifteen men which was setting on the top-rail, the way they howled you’d of thought something terrible had happened. Me and Cap’n Kidd don’t generally bother about gates. We usually makes our own through whatever happens to be in front of us. But them miners is a weakly breed, because as I rode out of town I seen the crowd dipping four or five of ’em into a hoss-trough to bring ’em to, on account of Cap’n Kidd having accidentally tromped on ’em.

Well, I rode out of the Gulch and up the ravine to the south, and come out into the high timbered country, and hit the old Injun trail Blink had told me about. It warn’t traveled much. I didn’t meet nobody after I left the Gulch. I figgered to hit Hell-Wind Pass at least a hour before sun-down which would give me plenty of time. Blink said the stage passed through there about sun-down. I’d have to bring back Brother Rembrandt on Cap’n Kidd, I reckoned, but that there hoss can carry double and still out-run and out-last any other hoss in the State of Nevada. I figgered on getting back to Teton about midnight or maybe a little later.

After I’d went several miles I come to Apache Canyon, which was a deep, narrer gorge, with a river at the bottom which went roaring and foaming along betwixt rock walls a hundred and fifty feet high. The old trail hit the rim at a place where the canyon warn’t only about seventy foot wide, and somebody had felled a whopping big pine tree on one side so it fell acrost and made a foot-bridge, where a man could walk acrost. They’d once been a gold strike in Apache Canyon, and a big camp there, but now it was plumb abandoned and nobody lived anywheres near it.

I turned east and follered the rim for about half a mile. Here I come into a old wagon road which was just about growed up with saplings now, but it run down into a ravine into the bed of the canyon, and they was a bridge acrost the river which had been built during the days of the gold rush. Most of it had done been washed away by head-rises, but a man could still ride a horse across what was left. So I done so and rode up a ravine on the other side, and come out on high ground again.

I’d rode a few hundred yards past the ravine when somebody said: “Hey!” and I wheeled with both guns in my hands. Out of the bresh s’antered a tall gent in a long frock tail coat and broad-brimmed hat.

“Who air you and what the hell you mean by hollerin’ ‘Hey!’ at me?” I demanded courteously, p’inting my guns at him. A Elkins is always perlite.

“I am the Reverant Rembrandt Brockton, my good man,” says he. “I am on my way to Teton Gulch to unite my niece and a young man of that camp in the bonds of holy matrimony.”

“The he—you don’t say!” I says. “Afoot?”

“I alit from the stage-coach at—ah—Hades-Wind Pass,” says he. “Some very agreeable cowboys happened to be awaiting the stage there, and they offered to escort me to Teton.”

“How come you knowed yore niece was wantin’ to be united in acrimony?” I ast.

“The cowboys informed me that such was the case,” says he.

“Where-at are they now?” I next inquore.

“The mount with which they supplied me went lame a little while ago,” says he. “They left me here while they went to procure another from a near-by ranch-house.”

“I dunno who’d have a ranch anywheres near here,” I muttered. “They ain’t got much sense leavin’ you here by yore high lonesome.”

“You mean to imply there is danger?” says he, blinking mildly at me.

“These here mountains is lousy with outlaws which would as soon kyarve a preacher’s gullet as anybody’s,” I said, and then I thought of something else. “Hey!” I says. “I thought the stage didn’t come through the Pass till sun-down?”

“Such was the case,” says he. “But the schedule has been altered.”

“Heck!” I says. “I was aimin’ to put this here gold on it which my saddle-bags is full of. Now I’ll have to take it back to Teton with me. Well, I’ll bring it out tomorrer and catch the stage then. Brother Rembrandt, I’m Breckinridge Elkins, of Bear Creek, and I come out here to meet you and escort you back to the Gulch, so’s you could unite yore niece and Blink Wiltshaw in the holy bounds of alimony. Come on. We’ll ride double.”

“But I must await my cowboy friends!” he said. “Ah, here they come now!”

I looked over to the east and seen about fifteen men ride into sight out of the bresh and move toward us. One was leading a hoss without no saddle onto it.

“Ah, my good friends!” beamed Brother Rembrandt. “They have procured a mount for me, even as they promised.”

He hauled a saddle out of the bresh, and says: “Would you please saddle my horse for me when they get here? I should be delighted to hold your rifle while you did so.”

I started to hand him my Winchester, when the snap of a twig under a hoss’s hoof made me whirl quick. A feller had just rode out of a thicket about a hundred yards south of me, and he was raising a Winchester to his shoulder. I recognized him instantly. If us Bear Creek folks didn’t have eyes like a hawk, we’d never live to git growed. It was Jake Roman!

Our Winchesters banged together. His lead fanned my ear and mine knocked him end-ways out of his saddle.

“Cowboys, hell!” I roared. “Them’s Harrison’s outlaws! I’ll save you, Brother Rembrandt!”

I swooped him up with one arm and gouged Cap’n Kidd with the spurs and he went from there like a thunderbolt with its tail on fire. Them outlaws come on with wild yells. I ain’t in the habit of running from people, but I was afeared they might do the Reverant harm if it come to a close fight, and if he stopped a hunk of lead, Blink might not git to marry his niece, and might git disgusted and go back to War Paint and start sparking Dolly Rixby again.

I was heading back for the canyon, aiming to make a stand in the ravine if I had to, and them outlaws was killing their hosses trying to git to the bend of the trail ahead of me, and cut me off. Cap’n Kidd was running with his belly to the ground, but I’ll admit Brother Rembrandt warn’t helping me much. He was laying acrost my saddle with his arms and laigs waving wildly because I hadn’t had time to set him comfortable, and when the horn jobbed him in the belly he uttered some words I wouldn’t of expected to hear spoke by a minister of the gospel.

Guns begun to crack and lead hummed past us, and Brother Rembrandt twisted his head around and screamed: “Stop that shootin’, you—sons of—! You’ll hit me!”

I thought it was kind of selfish of Brother Rembrandt not to mention me, too, but I said: “T’ain’t no use to remonstrate with them skunks, Reverant. They ain’t got no respeck for a preacher even.”

But to my amazement the shooting stopped, though them bandits yelled louder’n ever and flogged their cayuses. But about that time I seen they had me cut off from the lower canyon crossing, so I wrenched Cap’n Kidd into the old Injun trace and headed straight for the canyon rim as hard as he could hammer, with the bresh lashing and snapping around us and slapping Brother Rembrandt in the face when it whipped back. The outlaws yelled and wheeled in behind us, but Cap’n Kidd drawed away from them with every stride, and the canyon rim loomed just ahead of us.

“Pull up, you jack-eared son of Baliol!” howled Brother Rembrandt. “You’ll go over the edge!”

“Be at ease, Reverant,” I reassured him. “We’re goin’ over the log.”

“Lord have mercy on my soul!” he squalled, and shet his eyes and grabbed a stirrup leather with both hands, and then Cap’n Kidd went over that log like thunder rolling on Jedgment Day.

I doubt if they is another hoss west of the Pecos which would bolt out onto a log foot-bridge acrost a canyon a hundred fifty foot deep like that, but they ain’t nothing in this world Cap’n Kidd’s scairt of except maybe me. He didn’t slacken his speed none. He streaked acrost that log like it was a quarter-track, with the bark and splinters flying from under his hoofs, and if one foot had slipped a inch, it would of been Sally bar the door. But he didn’t slip, and we was over and on the other side almost before you could catch yore breath.

“You can open yore eyes now, Brother Rembrandt,” I said kindly, but he didn’t say nothing. He’d fainted. I shook him to wake him up, and in a flash he come to and give a shriek and grabbed my laig like a b’ar trap. I reckon he thought we was still on the log. I was trying to pry him loose when Cap’n Kidd chose that moment to run under a low-hanging oak tree limb. That’s his idee of a joke. That there hoss has got a great sense of humor.

I looked up just in time to see the limb coming, but not in time to dodge it. It was as big around as my thigh, and it took me smack acrost the wish-bone. We was going full speed, and something had to give way. It was the girths—both of ’em. Cap’n Kidd went out from under me, and me and Brother Rembrandt and the saddle hit the ground together.

I jumped up but Brother Rembrandt laid there going: “Wug wug wug!” like water running out of a busted jug. And then I seen them outlaws had dismounted off of their hosses and was coming acrost the bridge single file, with their Winchesters in their hands.

I didn’t waste no time shooting them misguided idjits. I run to the end of the foot-bridge, ignoring the slugs they slung at me. It was purty pore shooting, because they warn’t shore of their footing, and didn’t aim good. So I only got one bullet in the hind laig and was creased three or four other unimportant places—not enough to bother about.

I bent my knees and got hold of the end of the tree and heaved up with it, and them outlaws hollered and fell along it like ten pins, and dropped their Winchesters and grabbed holt of the log. I given it a shake and shook some of ’em off like persimmons off a limb after a frost, and then I swung the butt around clear of the rim and let go, and it went down end over end into the river a hundred and fifty feet below, with a dozen men still hanging onto it and yelling blue murder.

A regular geyser of water splashed up when they hit, and the last I seen of ’em they was all swirling down the river together in a thrashing tangle of arms and laigs and heads.

I remember Brother Rembrandt and run back to where he’d fell, but was already onto his feet. He was kind of pale and wild-eyed and his laigs kept bending under him, but he had hold of the saddle-bags and was trying to drag ’em into a thicket, mumbling kind of dizzily to hisself.

“It’s all right now, Brother Rembrandt,” I said kindly. “Them outlaws is plumb horse-de-combat now, as the French say. Blink’s gold is safe.”

“—!” says Brother Rembrandt, pulling two guns from under his coat tails, and if I hadn’t grabbed him, he would of undoubtedly shot me. We rassled around and I protested: “Hold on, Brother Rembrandt! I ain’t no outlaw. I’m yore friend, Breckinridge Elkins. Don’t you remember?”

His only reply was a promise to eat my heart without no seasoning, and he then sunk his teeth into my ear and started to chaw it off, whilst gouging for my eyes with both thumbs and spurring me severely in the hind laigs. I seen he was out of his head from fright and the fall he got, so I said sorrerfully: “Brother Rembrandt, I hate to do this. It hurts me more’n it does you, but we cain’t waste time like this. Blink is waitin’ to git married.” And with a sigh I busted him over the head with the butt of my six-shooter, and he fell over and twitched a few times and then lay limp.

“Pore Brother Rembrandt,” I sighed sadly. “All I hope is I ain’t addled yore brains so you’ve forgot the weddin’ ceremony.”

So as not to have no more trouble with him when, and if, he come to, I tied his arms and laigs with pieces of my lariat, and taken his weppins which was most surprizing arms for a circuit rider. His pistols had the triggers out of ’em, and they was three notches on the butt of one, and four on the other’n. Moreover he had a bowie knife in his boot, and a deck of marked kyards and a pair of loaded dice in his hip-pocket. But that warn’t none of my business.

About the time I finished tying him up, Cap’n Kidd come back to see if he’d killed me or just crippled me for life. To show him I can take a joke too, I give him a kick in the belly, and when he could git his breath again, and undouble hisself, I throwed the saddle on him. I spliced the girths with the rest of my lariat, and put Brother Rembrandt in the saddle and clumb on behind and we headed for Teton Gulch.

After a hour or so Brother Rembrandt come to and says kind of dizzily: “Was anybody saved from the typhoon?”

“Yo’re all right, Brother Rembrandt,” I assured him. “I’m takin’ you to Teton Gulch.”

“I remember,” he muttered. “It all comes back to me. Damn Jake Roman! I thought it was a good idea, but it seems I was mistaken. I thought we had an ordinary human being to deal with. I know when I’m licked. I’ll give you a thousand dollars to let me go.”

“Take it easy, Brother Rembrandt,” I soothed, seeing he was still delirious. “We’ll be to Teton in no time.”

“I don’t want to go to Teton!” he hollered.

“You got to,” I said. “You got to unite yore niece and Blink Wiltshaw in the holy bums of parsimony.”

“To hell with Blink Wiltshaw and my—niece!” he yelled.

“You ought to be ashamed usin’ sech langwidge, and you a minister of the gospel,” I reproved him sternly. His reply would of curled a Piute’s hair.

I was so scandalized I made no reply. I was just fixing to untie him, so’s he could ride more comfortable, but I thought if he was that crazy, I better not. So I give no heed to his ravings which growed more and more unbearable. In all my born days I never seen such a preacher.

It was shore a relief to me to sight Teton at last. It was night when we rode down the ravine into the Gulch, and the dance halls and saloons was going full blast. I rode up behind the Yaller Dawg Saloon and hauled Brother Rembrandt off with me and sot him on his feet, and he said, kind of despairingly: “For the last time, listen to reason. I got fifty thousand dollars cached up in the hills. I’ll give you every cent if you’ll untie me.”

“I don’t want no money,” I said. “All I want is for you to marry yore niece and Blink Wiltshaw. I’ll untie you then.”

“All right,” he said. “All right! But untie me now!”

I was just fixing to do it, when the bar-keep come out with a lantern and he shone it on our faces and said in a startled tone: “Who the hell is that with you, Elkins?”

“You wouldn’t never suspect it from his langwidge,” I says, “but it’s the Reverant Rembrandt Brockton.”

“Are you crazy?” says the bar-keep. “That’s Rattlesnake Harrison!”

“I give up,” said my prisoner. “I’m Harrison. I’m licked. Lock me up somewhere away from this lunatic.”

I was standing in a kind of daze, with my mouth open, but now I woke up and bellered: “What? Yo’re Harrison? I see it all now! Jake Roman overheard me talkin’ to Blink Wiltshaw, and rode off and fixed it with you to fool me like you done, so’s to git Blink’s gold! That’s why you wanted to hold my Winchester whilst I saddled yore cayuse.”

“How’d you ever guess it?” he sneered. “We ought to have shot you from ambush like I wanted to, but Jake wanted to catch you alive and torture you to death account of your horse bitin’ him. The fool must have lost his head at the last minute and decided to shoot you after all. If you hadn’t recognized him we’d had you surrounded and stuck up before you knew what was happening.”

“But now the real preacher’s gone on to Wahpeton!” I hollered. “I got to foller him and bring him back—”

“Why, he’s here,” said one of the men which was gathering around us. “He come in with his niece a hour ago on the stage from War Paint.”

“War Paint?” I howled, hit in the belly by a premonition. I run into the saloon, where they was a lot of people, and there was Blink and a gal holding hands in front of a old man with a long white beard, and he had a book in his hand, and t’other’n lifted in the air. He was saying: “—And I now pronounces you-all man and wife. Them which God had j’ined together let no snake-hunter put asunder.”

“Dolly!” I yelled. Both of ’em jumped about four foot and whirled, and Dolly Rixby jumped in front of Blink and spread her arms like she was shooing chickens.

“Don’t you tech him, Breckinridge Elkins!” she hollered. “I just married him and I don’t aim for no Humbolt grizzly to spile him!”

“But I don’t sabe all this—” I said dizzily, nervously fumbling with my guns which is a habit of mine when upsot.

Everybody in the wedding party started ducking out of line, and Blink said hurriedly: “It’s this way, Breck. When I made my pile so onexpectedly quick, I sent for Dolly to come and marry me like she’d promised the day after you left for the Yavapai. I was aimin’ to take my gold out today, like I told you, so me and Dolly could go to San Francisco on our honeymoon, but I learnt Harrison’s gang was watchin’ me, just like I told you. I wanted to git my gold out, and I wanted to git you out of the way before Dolly and her uncle got here on the War Paint stage, so I told you that lie about Brother Rembrandt bein’ on the Wahpeton stage. It was the only lie.”

“You said you was marryin’ a gal in Teton,” I accused fiercely.

“Well,” says he, “I did marry her in Teton. You know, Breck, all’s fair in love and war.”

“Now, now, boys,” said Brother Rembrandt—the real one, I mean. “The gal’s married, yore rivalry is over, and they’s no use holdin’ grudges. Shake hands and be friends.”

“All right,” I said heavily. No man cain’t say I ain’t a good loser. I was cut deep but I concealed my busted heart.

Leastways I concealed it all I was able to. Them folks which says I crippled Blink Wiltshaw with malice aforethought is liars which I’ll sweep the road with when I catches ’em. When my emotions is wrought up I unconsciously uses more of my strength than I realizes. I didn’t aim to break Blink’s arm when I shook hands with him; it was just the stress of my emotions. Likewise it was Dolly’s fault that her Uncle Rembrandt got throwed out a winder and some others got their heads banged. When she busted me with that cuspidor I knew that our love was dead forever. Tears come into my eyes as I waded through the crowd, and I had to move fast to keep from making a fool of myself. Them that was flang out of my way ought to have knowed it was done more in sorrer than in anger.

Gettin’ shot at by strangers and relatives is too plumb common to bother about, and I don’t generally pay no attention to it. But it’s kind of irritating to git shot at by yore best friend, even when yo’re as mild and gentle-natured as what I am. But I reckon I better explain. I’d been way up nigh the Oregon line, and was headin’ home when I happened to pass through the mining camp of Moose Jaw, which was sot right in the middle of a passle of mountains nigh as wild and big as the Humbolts. I was takin’ me a drink at the bar of the Lazy Elk Saloon and Hotel, when the barkeep says, after studying me a spell, he says, “You must be Breckinridge Elkins, of Bear Creek.”

I give the matter due consideration, and ’lowed as how I was.

“How come you knowed me?” I inquired suspiciously, because I hadn’t never been in Moose Jaw before, and he says, “Well, I’ve often heard tell of Breckinridge Elkins, and when I seen you, I figgered you must be him, because I don’t see how they can be two men in the world that big. By the way, they’s a friend of yore’n upstairs—Blaze Carson. He come up here from the southern part of the state, and I’ve often heered him brag about knowin’ you personal. He’s upstairs now, fourth door from the stair-head, on the right.”

Well, I remembered Blaze. He warn’t a Bear Creek man; he was from War Paint, but I didn’t hold that agen him. He was kind of addle-headed, but I don’t expeck everybody to be smart like me.

So I went upstairs and knocked on the door, and bam! went a gun inside and a .45 slug ripped through the door and taken a nick out of my ear. As I remarked before, it irritates me to be shot at by a man which has no reason to shoot at me, and my patience is quickly exhausted. So, without waiting for any more exhibitions of hospitality, I give a exasperated beller and knocked the door off its hinges and busted into the room over its rooins.

For a second I didn’t see nobody, but then I heard a kind of gurgle going on, and happened to remember that the door seemed kind of squishy when I tromped over it, so I knowed that whichever was in the room had got pinned under the door when I knocked it down.

So I reched under it with one hand and got him by the collar and hauled him out, and shore enough it was Blaze Carson. He was limp as a rag and glassy-eyed, and pale, and wild-looking, and was still vaguely trying to shoot me with his six-shooter when I taken it away from him.

“What the hell is the matter with you?” I demanded sternly, dangling him by the collar with one hand, whilst shaking him till his teeth rattled. “Air you got deliritus trimmins, or what, shootin’ at yore friends through the door?”

“Lemme down, Breck,” he gasped. “I didn’t know it was you. I thought it was Lobo Ferguson comin’ after my gold.”

So I sot him down and he grabbed a jug of licker and poured hisself a dram and his hand shaken so he spilled half of it down his neck when he tried to drink.

“Well?” I demanded. “Ain’t you goin’ to offer me a snort, dern it?”

“Excuse me, Breckinridge,” he apolergized. “I’m so dern jumpy I dunno what I’m doin’. I been livin’ in this here room for a week, too scairt to stick my head out. You see them buckskin pokes?” says he, p’inting at some bags on the bed. “Them is bustin’ full of nuggets. I been minin’ up the Gulch for over a year now, and I got myself a neat fortune in them bags. But it ain’t doin’ me no good.”

“What you mean?” I demanded.

“These mountains is full of outlaws,” says he. “They robs and murders every man which tries to take his gold out. The stagecoach has been stuck up so often nobody sends their dust out onto it no more. When a man makes his pile, he watches his chance and sneaks out through the mountains at night, with his gold on pack-mules. Sometimes he makes it and sometimes he don’t. That’s what I aimed to do. But them outlaws has got spies all over the camp. I know they got me spotted. I been afeared to make my break, and afeared if I didn’t, they’d git impatient and come right into camp and cut my throat. That’s what I thought when I heard you knock. Lobo Ferguson’s the big chief of ’em. I been squattin’ over this here gold with my pistol night and day, makin’ the barkeep bring my licker and grub up to me. I’m dern near loco!”

And he shaken like he had the aggers, and shivered and cussed kind of whimpery, and taken another dram, and cocked his pistol and sot there shakin’ like he’d saw a ghost or two.

“How’d you go if you snuck out?” I demanded.

“Up the ravine south of the camp and hit the old Injun path that winds up through Scalplock Pass,” says he. “Then I’d circle wide down to Wahpeton and grab the stagecoach there. I’m safe, onst I git to Wahpeton.”

“I’ll take yore gold out for you,” I says.

“But them outlaws’ll kill you!” says he.

“Naw, they won’t,” I says. “First place, they won’t know I got the gold. Second place, I’ll bust their heads if they start anything with me in the first place. Is this all the gold they is?” I ast.

“Ain’t it enough?” says he. “My hoss and pack-mule is in the stables behind the saloon—”

“I don’t need no pack-mule,” I says. “Cap’n Kidd can pack that easy.”

“And you, too?” he ast.

“You ought to know Cap’n Kidd well enough not to have to ast no sech dern fool question as that there,” I said irritably. “Wait till I git my saddlebags.”

Cap’n Kidd was getting fed out in the corral next to the hotel. I went out there and got my saddlebags, which is a lot bigger’n most, because my plunder has to be made to fit my size. They’re made outa three-ply elkskin, stitched with rawhide thongs, and a wildcat couldn’t claw his way out of ’em.

Well, I noticed quite a bunch of men standing around the corral looking at Cap’n Kidd, but thought nothing of it, because he is a hoss which naturally attracts attention.

But whilst I was getting my saddlebags, a long lanky cuss with long yaller whiskers come up and said, “Is that yore hoss in the corral?”

“If he ain’t he ain’t nobody’s,” I said.

“Well, he looks a lot like a hoss that was stole off my ranch six months ago,” he said, and I seen ten or fifteen hard-looking hombres gatherin’ around us. I laid down my saddlebags sudden-like and started to pull my guns, when it occurred to me that if I had a fight there, I might git arrested and it would interfere with me taking out Blaze’s gold.

“If that there is yore hoss,” I said, “you ought to be able to lead him out of that there corral.”

“Shore I can,” he says with a oath. “And what’s more, I aim to.”

“That’s the stuff, Bill,” somebody says. “Don’t let the big hillbilly tromple on yore rights!”

But I noticed some men in the crowd looked like they didn’t like it, but was scairt to say anything.

“All right,” I says to Bill, “here’s a lariat. Climb over that fence and go and put it on that hoss, and he’s yore’n.”

He looked at me suspiciously, but he taken the rope and clumb the fence and started towards Cap’n Kidd which was chawing on a block of hay in the middle of the corral, and Cap’n Kidd throwed up his head and laid back his ears and showed his teeth. Bill stopped sudden and turned pale, and said, “I—I don’t believe that there is my hoss, after all!”

“Put that lariat on him!” I roared, pulling my right-hand gun. “You say he’s yore’n; I say he’s mine. One of us is a liar and a hoss thief, and I aim to prove which’n it is! Gwan, before I ventilates yore yaller system with hot lead!”

He looked at me and he looked at Cap’n Kidd, and he turned bright green all over. He looked agen at my .45 which I now had cocked and p’inted at his long neck, which his Adam’s apple was going up and down like a monkey on a pole, and he begun to aidge towards Cap’n Kidd again, holding the rope behind him and sticking out one hand.

“Whoa, boy,” he says kind of shudderingly. “Whoa—good old feller—whoa, boy—ow!”

He let out a awful howl as Cap’n Kidd made a snap and bit a chunk out of his hide. He turned to run but Cap’n Kidd wheeled and let fly both heels which caught Bill in the seat of the britches, and his shriek of despair was horrible to hear as he went headfirst through the corral fence into a hoss trough on the other side. From this he ariz dripping water, blood and profanity. He shook a quivering fist at me and croaked, “You derned murderer! I’ll have yore life for this.”

“I don’t hold no conversation with hoss thieves,” I snorted, and picked up my saddlebags and stalked through the crowd which give back in a hurry on each side to let me through. And I noticed when I tromped on some fellers’ toes, they done their cussing under their breath, and pertended to be choking on their terbaccer when I glared back at ’em. Folks oughta keep their derned hoofs out of the way if they don’t want to be stepped on.

I taken the saddlebags up to Blaze’s room, and told him about Bill, thinking he’d be amoosed, but he got a case of aggers agen, and said, “That was one of Ferguson’s men! He meant to take yore hoss. It’s a old trick, and honest folks don’t dare interfere. Now they got you spotted! You better wait till night, at least.”

“Time, tide and a Elkins waits for no man!” I snorted, dumping the gold into the saddlebags. “If that yaller-whiskered coyote wants any trouble, he can git a bellyful. Tomorrer you git on the stagecoach and hit for Wahpeton. If I ain’t there, wait for me. I ought to pull in a day or so after you git there, anyway. And don’t worry about yore gold. It’ll be plumb safe in my saddlebags.”

“Don’t yell so loud,” begged Blaze. “The derned camp’s full of spies, and some of ’em may be downstairs.”

“I warn’t speakin’ above a whisper,” I said indignantly.

“That bull’s beller may pass for a whisper on Bear Creek,” says he, wiping off the perspiration, “but I bet they can hear it from one end of the Gulch to the other, at least.”

It’s a pitable sight to see a man with a case of the scairts; I shaken hands with him and left him pouring red licker down his gullet like so much water, and I swung the saddlebags over my shoulder and went downstairs, and the barkeep leaned over the bar and whispered to me, “Look out for Bill Price! He was in here a minute ago, lookin’ for trouble. He pulled out just before you come down, but he won’t be forgettin’ what yore hoss done to him!”

“Not when he tries to sit down, he won’t!” I agreed, and went on out to the corral, and they was a crowd of men watching Cap’n Kidd eat his hay, and one of ’em seen me and hollered, “Hey, boys, here comes the giant! He’s goin’ to saddle that man-eatin’ monster! Hey, Tom! Tell the boys at the bar!”

And here come a whole passel of fellers running out of all the saloons, and they lined the corral fence solid, and started laying bets whether I’d git the saddle on Cap’n Kidd, or git my brains kicked out. I thought miners must all be crazy; they ought to knowed I rode into camp on him and was able to saddle my own hoss.

Well, I saddled him, and throwed on the saddlebags, and clumb aboard, and he pitched about ten jumps like he always does when I first fork him—t’warn’t nothing, but them miners hollered like wild Injuns. And when he accidentally bucked hisself and me through the fence and knocked down a section of it along with about fifteen men which was setting on the toprail, the way they howled you’d of thought something terrible had happened. Me and Cap’n Kidd don’t generally bother about gates. We usually makes our own through whatever happens to be in front of us. But them miners is a weakly breed, because as I rode out of the town I seen the crowd dipping four or five of ’em into a hoss trough to bring ’em to, on account of Cap’n Kidd having accidentally stepped on ’em.

This trivial occurrence seemed to excite everybody so much nobody noticed me as I rode off, which suited me fine, because I am a modest man, shy and retiring by nature, which don’t crave no publicity. I didn’t see no sign of the feller they called Bill Price.

Well, I rode out of the Gulch and up the ravine to the south, and come out into the high-timbered country, and was casting around for the old Injun trail Blaze had told me about, when somebody said, “Hey!” I wheeled with both guns in my hands, and a long, lean, black-whiskered old cuss rode out of the bresh toward me.

“Who are you and what the hell you mean by hollerin’ ‘Hey!’ at me?” I demanded. A Elkins is always perlite.

“Air you the man with the man-eatin’ stallion?” he ast, and I says, “I dunno what yo’re talkin’ about. This here hoss is Cap’n Kidd, which I catched down in the Humbolt country, and a milder mannered critter never kicked the brains out of a mountain lion.”

“He’s the biggest hoss I ever see,” he said. “Looks fast, though.”

“Fast?” says I, with the pride a Elkins always takes in his hoss flesh. “Cap’n Kidd can outrun anything in this State, and carry me, and you, and all this here gold in these saddlebags whilst doing it.” Then I shaken my head in disgust, because I hadn’t meant to mention the gold, but I couldn’t see what harm it would do.

“Well,” he said, “you’ve made a enemy of Bill Price, one of Lobo Ferguson’s gunmen, and as pizenous a critter as ever wore boot leather. He come by here a few minutes ago, frothin’ at the mouth, and swearin’ to have yore heart’s blood. He’s headin’ up into the mountains to round up forty or fifty of his gang and take yore sculp.”

“Well, what about it?” I inquired, not impressed. Somebody is always wanting my life, and forty or fifty outlaws ain’t no odds to a Elkins.

“They’ll waylay you,” he predicted. “Yo’re a fine, upstandin’ young man, which deserves a better fate’n to git dry-gulched by a passle of lowdown bandit varmints. I’m jest headin’ for my cabin up in the hills. It’s a right smart piece off the trail. Whyn’t you come along with me and lay low till they’ve give up the search? They won’t find you there.”

“I ain’t in the habit of hidin’ from my enemies,” I begun, when suddenly I remembered that there gold in my saddlebags. It was my duty to git it to Wahpeton. If I was to tangle with Ferguson’s gang, they was just a slim chance that they might down me, shooting from the bresh, and run off with pore Blaze’s hard-earned dough. It was hard to do, but I decided I’d avoid a battle till after I’d give Blaze his gold safe and sound. Then, I was determined, I’d come back and frail the daylights outa Lobo Ferguson for forcing me into this here humiliating position.

“Lead on!” I says. “Lead me to yore hermitage in the wildwood, out of the reach of the maddenin’ crowd and Lobo Ferguson’s bullets. But I imposes a sacred trust of secrecy onto you. Let the world never know that Breckinridge Elkins, the pride of Bear Creek, took to kiver to dodge a mangy passle of minin’ country road-agents.”

“My lips is sealed,” says he. “Yore fatal secret is safe with Polecat Rixby. Foller me.”

He led me through the bresh till we hit the old Injun trail, which warn’t more’n a trace through the hills, and we pushed hard all the rest of the day, not seeing anybody coming or going.

“They’ll be lookin’ for you in Moosejaw,” said the Polecat. “When they don’t find you, they’ll comb the hills. But they’ll never find my cabin, even if they knowed you was hidin’ there, which they don’t.”

Close to sundown we turned off the trail onto a still dimmer trace that led east, and wound amongst crags and boulders till a snake would of broke his back tryin’ to foller it, and just before it got good and dark we come to a log bridge acrost a deep, narrer canyon. They was a river at the bottom of that there canyon, which was awful swift, and went roaring and foaming along betwixt rock walls a hundred feet high. But at one place the canyon wasn’t only about seventy foot wide, and they’d felled a whopping big pine tree on one side so it fell acrost and made a bridge, and the top side was trimmed down flat so a hoss could walk acrost, though the average hoss wouldn’t like it very much. Polecat’s hoss was used to it, but he was scairt jest the same. But they ain’t nothin’ between Kingdom Come and Powder River that Cap’n Kidd’s scairt of, except maybe me, and he walzed acrost that there tree like he was on a quartertrack.

The path wound through a lot of bresh on the other side, and so did we, and after awhile we come to a cabin built nigh the foot of a big cliff. It was on a kind of thick-timbered shelf, and the land fell away in a gradual slope to a breshy run, and they was a clear spring nigh the aidge of the bresh. It was a good place for a cabin.

They was a stone corral built up agen the foot of the cliff, and it looked to be a dern sight bigger’n Polecat oughta need for his one saddle hoss and the three pack hosses which was in there, but I have done learnt that there ain’t no accounting for the way folks builds things. Polecat told me to turn Cap’n Kidd loose in the corral, but I knowed if I done that they would be one dead saddle hoss and three dead pack hosses in there before midnight, so I turned him loose to graze, knowing he wouldn’t go far. Cap’n Kidd likes me too much to run off and leave me, regardless of the fact that he frequently tries to kill me.

By this time it was night, and Polecat said come in and he’d fix up a snack of supper. So we went in and he lit a candle and made coffee and fried bacon and sot out some beans and corn pone, and he taken a good look at me settin’ there at the table all ready to fall to, and he fried up a lot more bacon and sot out more beans. He hadn’t talked much all day, and now he was about as talkative as a clam with the lockjaw. He was jumpy, too, and nervous, and I decided he was scairt Lobo Ferguson might find him after all, and do vi’lence to him for hiding me. It’s a dreary sight to see a grown man scairt of something. Being scairt must be some kind of a disease; I cain’t figger it out no other way.

I was watching Polecat, even if I didn’t seem to, because that’s a habit us Bear Creek folks gits into; if we didn’t watch each other awful close, we’d never live to git grown. So when he poured a lot of white-looking powder into my coffee out of a box on the shelf, he didn’t think I seen him, but I did, and I noticed he didn’t put none in his’n. But I didn’t say nothing, because it ain’t perlite to criticize a man’s cooking when yo’re his guest; if Polecat had some new-fangled way of making coffee t’warn’t for me to object.

He sot the grub on the table and sot down opposite me, with his head down, and looking at me kinda furtive-like from under his brows, and I laid into the grub and et hearty.

“Yore coffee’ll git cold,” he said presently, and I remembered it, and emptied the cup at one gulp, and it was the best coffee I ever drunk.

“Ha!” says I, smacking my lips. “You ain’t much shakes of a man to look at, Polecat, but you shore can b’ile coffee! Gimme another cup! What’s the matter; you ain’t eatin’ hardly anything?”

“I ain’t a very hearty eater,” he mumbled. “You—you want some more coffee?”

So I drunk six more cups, but they didn’t taste near as good as the first, and I knowed it was because he didn’t put none of that white stuff in ’em, but I didn’t say nothing because it wouldn’t have been perlite.

After I’d cleaned up everything in sight, I said I’d help him wash the pans and things, but he said, kind of funny-like, “Let ’em go. I—we can do that—tomorrer. How—how do you feel?”

“I feel fine,” I said. “You can make coffee nigh as good as I can. Le’s sit down out on the stoop. I hate to be inside walls any more’n I have to.”

He follered me out and we sot down and I got to telling him about the Bear Creek country, because I was kind of homesick; but he didn’t talk at all, just sot there staring at me in a most pecooliar manner. Finally I got sleepy and said I believed I’d go to bed, so he got a candle and showed me where I was to sleep. The cabin had two rooms, and my bunk was in the back room. They wasn’t any outside door to that room, just the door in the partition, but they was a winder in the back wall.

I throwed my saddlebags under the bunk, and leaned my Winchester agen the wall, and sot down on the bunk and started pulling off my boots, and Polecat stood in the door looking at me, with the candle in his hand, and a very strange expression on his face.

“You feel good?” he says. “You—you ain’t got no bellyache nor nothin’?”

“Hell, no!” I says heartily. “What I want to have a bellyache for? I never had one of them things in my life, only onst when my brother Buckner shot me in the belly with a buffalo gun. Us Elkinses is healthy.”

He shaken his head and muttered something in his beard, and backed out of the room, closing the door behind him. But the light didn’t go out in the next room. I could see it shining through the crack of the door. It struck me that Polecat was acting kind of queer, and I begun to wonder if he was crazy or something. So I riz up in my bare feet and snuck over to the door, and looked through the crack.

Polecat was standing by the table with his back to me, and he had that box he’d got the white stuff out of, and he was turning it around in his hand, and shaking his head and muttering to hisself.

“I didn’t make no mistake,” he mumbled. “This is the right stuff, all right. I put dern near a handful in his coffee. That oughta been enough for a elephant. I don’t understand it. I wouldn’t believe it if I hadn’t saw it myself.”

Well, I couldn’t make no sense out of it, and purty soon he sot the box back on the shelf behind some pans and things, and snuck out the door. But he didn’t take his rifle, and he left his pistol belt hanging on a peg nigh the door. What he took with him was the fire-tongs off of the hearth. I decided he must be a little locoed from living by hisself, and I went back to bed and went to sleep.

It was some hours later when I woke up and sot up with my guns in my hands, and demanded, “Who’s that? Speak up before I drills you.”

“Don’t shoot,” says the voice of Polecat Rixby, emanating from the shadowy figger hovering nigh my bunk. “It’s just me. I just wanted to see if you wanted a blanket. It gits cold up here in these mountains before mornin’.”

“When it gits colder’n fifteen below zero,” I says, “I generally throws a saddle blanket over me. This here’s summertime. Gwan back to bed and lemme git some sleep.”

I could of swore he had one of my boots in his hand when I first woke up, but he didn’t have it when he went out. I went back to sleep and I slept so sound it seemed like I hadn’t more’n laid back till daylight was oozing through the winder.

I got up and pulled on my boots and went into the other room, and coffee was b’iling, and bacon was frying onto a skillet, but Polecat warn’t in there. I laughed when I seen he’d just sot one place on the table. He’d lived by hisself so much he’d plump forgot he had company for breakfast. I went over to the shelf where he’d got the white stuff he put in my coffee, and retched back and pulled out the box. It had some letters onto it, and while I couldn’t read very good then, I knowed the alphabet, and was considered a highly educated man on Bear Creek. I spelled them letters out and they went “A-r-s-e-n-i-c.” It didn’t mean nothing to me, so I decided it was some foreign word for a new-fangled coffee flavor. I decided the reason Polecat didn’t put none in his coffee was because he didn’t have enough for both of us, and wanted to be perlite to his guest. But they was quite a bit of stuff left in the box. I heard him coming back just then, so I put it back on the shelf and went over by the table.

He come through the door with a armload of wood, and when he seen me he turned pale under his whiskers and let go the wood and it fell onto the floor. Some good-sized chunks bounced off of his feet but he didn’t seem to notice it.

“What the heck’s the matter with you?” I demanded. “Yo’re as jumpy as Blaze Carson.”

He stood there licking his lips for a minute, and then he says faintly, “It’s my nerves. I’ve lived up here so long by myself I kind of forgot I had company. I apolergizes.”

“Aw, hell, don’t apolergize,” I said. “Just fry some more bacon.”

So he done it, and pretty soon we sot down and et, and the coffee was purty sorry that morning.

“How long you reckon I ought to hide out here?” I ast, and he said, “You better stay here today and tomorrer. Then you can pull out, travelin’ southwest, and hit the old Injun trail again just this side of Scalplock Pass. Did—did you shake out yore boots this mornin’?”

“Naw,” I said. “Why?”

“Well,” he says, “they’s a awful lot of varmints around here, and sometimes they crawls into the cabin. I’ve found Santa Fes and stingin’ lizards in my boots some mornins.”

“I didn’t look,” I says, drinking my fifth cup of coffee, “but now you mention it, I believe they must be a flea in my left boot. I been feelin’ a kind of ticklin’.”

So I pulled the boot off, and retched in my hand and pulled it out, and it warn’t a flea at all, but a tarantula as big as your fist. I squshed it betwixt my thumb and forefinger and throwed it out the door, and Polecat looked at me kind of wild-like and said, “Did—did it bite you?”

“It’s been nibblin’ on my toe for the past half hour or so,” I said, “but I thought it was just a flea.”

“But my God!” he wailed. “Them things is pizen! I’ve seen men die from bein’ bit by ’em!”

“You mean to tell me men in these parts is so puny they suffers when a tranchler bites ’em?” I says. “I never heard of nothin’ so derned effeminate! Pass the bacon.”

He done so in a kind of pale silence, and after I had mopped up all the grease out of my plate with the last of the corn pone, I ast, “What does a-r-s-e-n-i-c spell?”

He was jest taking a swig of coffee and he strangled and sprayed it all over the table and fell backwards off his stool and would probably have choked to death if I hadn’t pounded him in the back.

“Don’t you know what arsenic is?” he gurgled when he could talk, and he was shaking like he had the aggers.

“Never heard of it,” I said, and he hove a shuddering sigh and said, “It’s a Egyptian word which means sugar.”

“Oh,” I said, and he went over and sot down and held his head in his hands like he was sick at the stummick. He shore was a queer-acting old codger.

Well, I seen the fire needed some wood, so I went out and got a armload and started back into the cabin, and jest as I sot a foot on the stoop bam! went a Winchester inside the cabin, and a .45-70 slug hit me a glancing lick on the side of the head and ricocheted off down towards the run.

“What the hell you doin’?” I roared angrily, and Polecat’s pale face appeared at the door, and he said, “Excuse me, Elkins! I war just cleanin’ my rifle-gun and it went off accidental!”

“Well, be careful,” I advised, shaking the blood off. “Glancin’ bullets is dangerous. It might of hit Cap’n Kidd.”

“Don’t you want to give yore hoss some corn?” he says. “They’s plenty out there in that shed nigh the corral.”

I thought that was a good idee, so I got a sack and dumped in about a bushel, because Cap’n Kidd is as hearty a eater as what I am, and I went down the run looking for him, and found him mowing down the high grass like a reaping machine, and he neighed with joy at the sight of the corn. Whilst he was gorging I went down the trail a ways to see if they was any outlaws sneaking up it, but I didn’t see no signs of none.

It was about noon when I got back to the cabin, and Polecat warn’t nowheres in sight, so I decided I’d cook dinner. I fried up a lot of bacon and fixed some bread and beans and potaters, and b’iled a whopping big pot of coffee, and whilst it was b’iling I emptied all the Gypshun sugar they was in the box into it, and taken a good swig, and it was fine. I thought foreigners ain’t got much sense, but they shore know how to make sugar.

I was putting the things on the table when Polecat came in looking kind of pale and wayworn, but he perked up when he seen the grub, and sot down and started to eat with a better appertite than he’d been showing. I was jest finishing my first cup of coffee when he taken a swig of his’n, and he spit it out on the floor and said, “What in hell’s the matter with this here coffee?”

Now, despite the fact that I am timid and gentle as a lamb by nature, they is one thing I will not endure, and that is for anybody to criticize my cooking. I am the best coffee-maker in Nevada, and I’ve crippled more’n one man for disagreeing with me. So I said sternly, “There ain’t nothin’ the matter with that there coffee.”

“Well,” he said, “I cain’t drink it.” And he started to pour it out.

At that I was overcome by culinary pride.

“Stop that!” I roared, jerking out one of my .45’s. “They is a limit to every man’s patience, and this here’s mine! Even if I am yore guest, you cain’t sneer at my coffee! Sech is a deadly insult, and not to be put up with by any man of spirit and self-respect! You drink that there coffee and display a proper amount of admiration for it, by golly!

“Yore lack of good taste cuts me to the marrer of my soul,” I continued bitterly, as he lifted the cup to his lips in fear and trembling. “After I’d done gone to all the trouble of makin’ that coffee specially good, and even flavorin’ it with all the white stuff they was in that box on the shelf!”

At that he screeched, “Murder!” and fell offa his stool backwards, spitting coffee in every direction. He jumped up and bolted for the door, but I grabbed him, and he pulled a bowie out of his boot and tried to stab me, all the time yowling like a catamount. Irritated at this display of bad manners, I taken the knife away from him and slammed him back down on the stool so hard it broke off all three of the laigs, and he rolled on the floor again, letting out ear-splitting screams.

By this time I was beginning to lose my temper, so I pulled him up and sot him down on the bench I’d been sitting on, and shoved the coffee pot under his nose with one hand and my .45 with the other.

“This is the wust insult I ever had offered to me,” I growled bloodthirstily. “So you’d do murder before you’d drink my coffee, hey? Well, you empty that there pot before you put her down, and you smack yore lips over it, too, or I’ll—”

“It’s murder!” he howled, twisting his head away from the pot. “I ain’t ready to die! I got too many sins a-stainin’ my soul! I’ll confess! I’ll tell everything! I’m one of Ferguson’s men! This here is the hideout where they keeps the hosses they steals, only they ain’t none here now. Bill Price was in the Lazy Elk Bar and heard you talkin’ to Blaze Carson about totin’ out his gold for him. Bill figgered it would take the whole gang to down you, so he lit out for ’em, and told me to try to git you up to my cabin if I could work it, and send up a smoke signal when I did, so the gang would come and murder you and take the gold.

“But when I got you up here, I decided to kill you myself and skip out with the gold, whilst the gang was waitin’ for my signal. You was too big for me to tackle with a knife or a gun, so I put pizen in yore coffee, and when that didn’t work I catched a tranchler last night with the tongs and dropped it into yore boot. This mornin’ I got desperate and tried to shoot you. Don’t make me drink that pizen coffee. I’m a broken man. I don’t believe mortal weppins can kill you. Yo’re a jedgment sent onto me because of my evil ways. If you’ll spare my life, I swear I’ll go straight from now on!”

“What I care how you go, you back-whiskered old sarpent?” I snarled. “My faith in humanity has been give a awful lick. You mean to tell me that there arsenic stuff is pizen?”

“It’s considered shore death to ordinary human beings,” says he.

“Well, I’ll be derned!” I says. “I never tasted nothin’ I liked better. Say!” I says, hit by another thought, “when you was out of the cabin awhile ago, did you by any chance build that there signal smoke?”

“I done so,” he admitted. “Up on top of the cliff. Ferguson and his gang is undoubtedly on their way here now.”

“Which way will they come?” I ast.

“Along the trail from the west,” says he. “Like we come.”

“All right,” I says, snatching up my Winchester, and the saddlebags in the other hand. “I’ll ambush ’em on this side of the gorge. I’m takin’ the gold along with me in case yore natural instincts overcomes you to the extent of lightin’ a shuck with it whilst I’m massacreein’ them idjits.”

I run out and whistled for Cap’n Kidd and jumped onto him bareback and went lickety-split through the bresh till I come to the canyon. And by golly, just as I jumped off of Cap’n Kidd and run through the bushes to the edge of the gorge, out of the bresh on the other side come ten men on horses, with Winchesters in their hands, riding hard. I reckoned the tall, lean, black-whiskered devil leading was Ferguson; I recognized Bill Price right behind him.

They couldn’t see me for the bushes, and I drawed a bead on Ferguson and pulled the trigger. And the hammer just clicked. Three times I worked the lever and jerked the trigger, and every time the derned gun snapped. By that time them outlaws had reached the bridge and strung out on it single-file, Ferguson in the lead. In another minute they’d be acrost, and my chance of ambushing ’em would be plumb sp’iled.

I throwed down my Winchester and busted out of the bresh and they seen me and started yelling, and Ferguson started shooting at me, but the others didn’t dare shoot for fear of hitting him, and some of the hosses started rearing, and the men was fighting to keep ’em from falling offa the bridge, but the whole passle come surging on. But I got to the end of the bridge in about three jumps, paying no attention to the three slugs Ferguson throwed into various parts of my anatomy. I bent my knees and got hold of the end of the tree and heaved up with it. It was such a big tree and had so many hosses and men on it even I couldn’t lift it very high, but that was enough. I braced my laigs and swung the end around clear of the rim and let go and it went end over end a hundred feet down into the canyon, taking all them outlaws and their hosses along with it, them a-yelling and squalling like the devil. A regular geyer of water splashed up when they hit, and the last I seen of ’em they was all swirling down the river together in a thrashing tangle of arms and laigs and heads and manes.

Whilst I stood looking after ’em, Polecat Rixby bust out of the bresh behind me, and he give a wild look, and shaken his head weakly, and then he said, “I forgot to tell you—I taken the powder out of the ca’tridges in yore Winchester this mornin’ whilst you was gone.”

“This is a hell of a time to be tellin’ me about it,” I says. “But it don’t make no difference now.”

“I suppose it’s too trivial to mention,” says he, “but it looks to me like you been shot in the hind laig and the hip and the shoulder.”

“It’s quite likely,” I agreed. “And if you really want to make yoreself useful, you might take this bowie and help me dig the lead out. Then I’m headin’ for Wahpeton. Blaze’ll be waitin’ for his gold, and I want to git me some of that there arsenic stuff. It makes coffee taste better’n skunk ile or rattlesnake pizen.”