Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

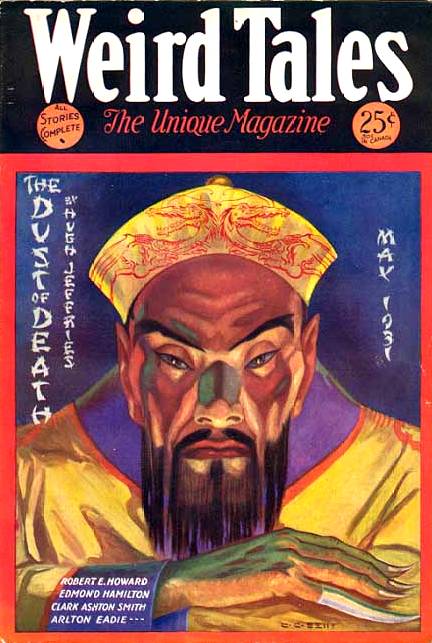

Published in Weird Tales, Vol. 17, No. 3 (April-May 1931).

There were, I remember, six of us in Conrad’s bizarrely fashioned study, with its queer relics from all over the world and its long rows of books which ranged from the Mandrake Press edition of Boccaccio to a Missale Romanum, bound in clasped oak boards and printed in Venice, 1740. Clemants and Professor Kirowan had just engaged in a somewhat testy anthropological argument: Clemants upholding the theory of a separate, distinct Alpine race, while the professor maintained that this so-called race was merely a deviation from an original Aryan stock—possibly the result of an admixture between the southern or Mediterranean races and the Nordic people.

“And how,” asked Clemants, “do you account for their brachycephalicism? The Mediterraneans were as long-headed as the Aryans: would admixture between these dolichocephalic peoples produce a broad-headed intermediate type?”

“Special conditions might bring about a change in an originally long-headed race,” snapped Kirowan. “Boaz has demonstrated, for instance, that in the case of immigrants to America, skull formations often change in one generation. And Flinders Petrie has shown that the Lombards changed from a long-headed to a round-headed race in a few centuries.”

“But what caused these changes?”

“Much is yet unknown to science,” answered Kirowan, “and we need not be dogmatic. No one knows, as yet, why people of British and Irish ancestry tend to grow unusually tall in the Darling district of Australia—Cornstalks, as they are called—or why people of such descent generally have thinner jaw-structures after a few generations in New England. The universe is full of the unexplainable.”

“And therefore the uninteresting, according to Machen,” laughed Taverel.

Conrad shook his head. “I must disagree. To me, the unknowable is most tantalizingly fascinating.”

“Which accounts, no doubt, for all the works on witchcraft and demonology I see on your shelves,” said Ketrick, with a wave of his hand toward the rows of books.

And let me speak of Ketrick. Each of the six of us was of the same breed—that is to say, a Briton or an American of British descent. By British, I include all natural inhabitants of the British Isles. We represented various strains of English and Celtic blood, but basically, these strains are the same after all. But Ketrick: to me the man always seemed strangely alien. It was in his eyes that this difference showed externally. They were a sort of amber, almost yellow, and slightly oblique. At times, when one looked at his face from certain angles, they seemed to slant like a Chinaman’s.

Others than I had noticed this feature, so unusual in a man of pure Anglo-Saxon descent. The usual myths ascribing his slanted eyes to some pre-natal influence had been mooted about, and I remember Professor Hendrik Brooler once remarked that Ketrick was undoubtedly an atavism, representing a reversion of type to some dim and distant ancestor of Mongolian blood—a sort of freak reversion, since none of his family showed such traces.

But Ketrick comes of the Welsh branch of the Cetrics of Sussex, and his lineage is set down in the Book of Peers. There you may read the line of his ancestry, which extends unbroken to the days of Canute. No slightest trace of Mongoloid intermixture appears in the genealogy, and how could there have been such intermixture in old Saxon England? For Ketrick is the modern form of Cedric, and though that branch fled into Wales before the invasion of the Danes, its male heirs consistently married with English families on the border marches, and it remains a pure line of the powerful Sussex Cedrics—almost pure Saxon. As for the man himself, this defect of his eyes, if it can be called a defect, is his only abnormality, except for a slight and occasional lisping of speech. He is highly intellectual and a good companion except for a slight aloofness and a rather callous indifference which may serve to mask an extremely sensitive nature.

Referring to his remark, I said with a laugh: “Conrad pursues the obscure and mystic as some men pursue romance; his shelves throng with delightful nightmares of every variety.”

Our host nodded. “You’ll find there a number of delectable dishes—Machen, Poe, Blackwood, Maturin—look, there’s a rare feast—Horrid Mysteries, by the Marquis of Grosse—the real Eighteenth Century edition.”

Taverel scanned the shelves. “Weird fiction seems to vie with works on witchcraft, voodoo and dark magic.”

True; historians and chronicles are often dull; tale-weavers never—the masters, I mean. A voodoo sacrifice can be described in such a dull manner as to take all the real fantasy out of it, and leave it merely a sordid murder. I will admit that few writers of fiction touch the true heights of horror—most of their stuff is too concrete, given too much earthly shape and dimensions. But in such tales as Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher, Machen’s Black Seal and Lovecraft’s Call of Cthulhu—the three master horror-tales, to my mind—the reader is borne into dark and outer realms of imagination.

“But look there,” he continued, “there, sandwiched between that nightmare of Huysmans’, and Walpole’s Castle of Otranto—Von Junzt’s Nameless Cults. There’s a book to keep you awake at night!”

“I’ve read it,” said Taverel, “and I’m convinced the man is mad. His work is like the conversation of a maniac—it runs with startling clarity for awhile, then suddenly merges into vagueness and disconnected ramblings.”

Conrad shook his head. “Have you ever thought that perhaps it is his very sanity that causes him to write in that fashion? What if he dares not put on paper all he knows? What if his vague suppositions are dark and mysterious hints, keys to the puzzle, to those who know?”

“Bosh!” This from Kirowan. “Are you intimating that any of the nightmare cults referred to by Von Junzt survive to this day—if they ever existed save in the hag-ridden brain of a lunatic poet and philosopher?”

“Not he alone used hidden meanings,” answered Conrad. “If you will scan various works of certain great poets you may find double meanings. Men have stumbled onto cosmic secrets in the past and given a hint of them to the world in cryptic words. Do you remember Von Junzt’s hints of ‘a city in the waste’? What do you think of Flecker’s line:”

‘Pass not beneath! Men say there blows in stony deserts still a rose

But with no scarlet to her leaf—and from whose heart no perfume flows.’

“Men may stumble upon secret things, but Von Junzt dipped deep into forbidden mysteries. He was one of the few men, for instance, who could read the Necronomicon in the original Greek translation.”

Taverel shrugged his shoulders, and Professor Kirowan, though he snorted and puffed viciously at his pipe, made no direct reply; for he, as well as Conrad, had delved into the Latin version of the book, and had found there things not even a cold-blooded scientist could answer or refute.

“Well,” he said presently, “suppose we admit the former existence of cults revolving about such nameless and ghastly gods and entities as Cthulhu, Yog Sothoth, Tsathoggua, Gol-goroth, and the like, I can not find it in my mind to believe that survivals of such cults lurk in the dark corners of the world today.”

To our surprise Clemants answered. He was a tall, lean man, silent almost to the point of taciturnity, and his fierce struggles with poverty in his youth had lined his face beyond his years. Like many another artist, he lived a distinctly dual literary life, his swashbuckling novels furnishing him a generous income, and his editorial position on The Cloven Hoof affording him full artistic expression. The Cloven Hoof was a poetry magazine whose bizarre contents had often aroused the shocked interest of the conservative critics.

“You remember Von Junzt makes mention of a so-called Bran cult,” said Clemants, stuffing his pipe-bowl with a peculiarly villainous brand of shag tobacco. “I think I heard you and Taverel discussing it once.”

“As I gather from his hints,” snapped Kirowan, “Von Junzt includes this particular cult among those still in existence. Absurd.”

Again Clemants shook his head. ”When I was a boy working my way through a certain university, I had for roommate a lad as poor and ambitious as I. If I told you his name, it would startle you. Though he came of an old Scotch line of Galloway, he was obviously of a non-Aryan type.

“This is in strictest confidence, you understand. But my roommate talked in his sleep. I began to listen and put his disjointed mumbling together. And in his mutterings I first heard of the ancient cult hinted at by Von Junzt; of the king who rules the Dark Empire, which was a revival of an older, darker empire dating back into the Stone Age; and of the great, nameless cavern where stands the Dark Man—the image of Bran Mak Morn, carved in his likeness by a master-hand while the great king yet lived, and to which each worshipper of Bran makes a pilgrimage once in his or her lifetime. Yes, that cult lives today in the descendants of Bran’s people—a silent, unknown current it flows on in the great ocean of life, waiting for the stone image of the great Bran to breathe and move with sudden life, and come from the great cavern to rebuild their lost empire.”

“And who were the people of that empire?” asked Ketrick.

“Picts,” answered Taverel, “doubtless the people known later as the wild Picts of Galloway were predominantly Celtic—a mixture of Gaelic, Cymric, aboriginal and possibly Teutonic elements. Whether they took their name from the older race or lent their own name to that race, is a matter yet to be decided. But when Von Junzt speaks of Picts, he refers specifically to the small, dark, garlic-eating peoples of Mediterranean blood who brought the Neolithic culture into Britain. The first settlers of that country, in fact, who gave rise to the tales of earth spirits and goblins.”

“I can not agree to that last statement,” said Conrad. ”These legends ascribe a deformity and inhumanness of appearances to the characters. There was nothing about the Picts to excite such horror and repulsion in the Aryan peoples. I believe that the Mediterraneans were preceded by a Mongoloid type, very low in the scale of development, whence these tales—”

“Quite true,” broke in Kirowan, “but I hardly think they preceded the Picts, as you call them, into Britain. We find troll and dwarf legends all over the Continent, and I am inclined to think that both the Mediterranean and Aryan people brought these tales with them from the Continent. They must have been of extremely inhuman aspect, those early Mongoloids.”

“At least,” said Conrad, “here is a flint mallet a miner found in the Welsh hills and gave to me, which has never been fully explained. It is obviously of no ordinary Neolithic make. See how small it is, compared to most implements of that age; almost like a child’s toy; yet it is surprisingly heavy and no doubt a deadly blow could be dealt with it. I fitted the handle to it, myself, and you would be surprized to know how difficult it was to carve it into a shape and balance corresponding with the head.”

We looked at the thing. It was well made, polished somewhat like the other remnants of the Neolithic I had seen, yet as Conrad said, it was strangely different. Its small size was oddly disquieting, for it had no appearance of a toy, otherwise. It was as sinister in suggestion as an Aztec sacrificial dagger. Conrad had fashioned the oaken handle with rare skill, and in carving it to fit the head, had managed to give it the same unnatural appearance as the mallet itself had. He had even copied the workmanship of primal times, fixing the head into the cleft of the haft with rawhide.

“My word!” Taverel made a clumsy pass at an imaginary antagonist and nearly shattered a costly Shang vase. “The balance of the thing is all off-center; I’d have to readjust all my mechanics of poise and equilibrium to handle it.”

“Let me see it,” Ketrick took the thing and fumbled with it, trying to strike the secret of its proper handling. At length, somewhat irritated, he swung it up and struck a heavy blow at a shield which hung on the wall nearby. I was standing near it; I saw the hellish mallet twist in his hand like a live serpent, and his arm wrenched out of line; I heard a shout of alarmed warning—then darkness came with the impact of the mallet against my head.

Slowly I drifted back to consciousness. First there was dull sensation with blindness and total lack of knowledge as to where I was or what I was; then vague realization of life and being, and a hard something pressing into my ribs. Then the mists cleared and I came to myself completely.

I lay on my back half-beneath some underbrush and my head throbbed fiercely. Also my hair was caked and clotted with blood, for the scalp had been laid open. But my eyes traveled down my body and limbs, naked but for a deerskin loincloth and sandals of the same material, and found no other wound. That which pressed so uncomfortably into my ribs was my ax, on which I had fallen.

Now an abhorrent babble reached my ears and stung me into clear consciousness. The noise was faintly like language, but not such language as men are accustomed to. It sounded much like the repeated hissing of many great snakes.

I stared. I lay in a great, gloomy forest. The glade was overshadowed, so that even in the daytime it was very dark. Aye—that forest was dark, cold, silent, gigantic and utterly grisly. And I looked into the glade.

I saw a shambles. Five men lay there—at least, what had been five men. Now as I marked the abhorrent mutilations my soul sickened. And about clustered the—Things. Humans they were, of a sort, though I did not consider them so. They were short and stocky, with broad heads too large for their scrawny bodies. Their hair was snaky and stringy, their faces broad and square, with flat noses, hideously slanted eyes, a thin gash for a mouth, and pointed ears. They wore the skins of beasts, as did I, but these hides were but crudely dressed. They bore small bows and flint-tipped arrows, flint knives and cudgels. And they conversed in a speech as hideous as themselves, a hissing, reptilian speech that filled me with dread and loathing.

Oh, I hated them as I lay there; my brain flamed with white-hot fury. And now I remembered. We had hunted, we six youths of the Sword People, and wandered far into the grim forest which our people generally shunned. Weary of the chase, we had paused to rest; to me had been given the first watch, for in those days, no sleep was safe without a sentry. Now shame and revulsion shook my whole being. I had slept—I had betrayed my comrades. And now they lay gashed and mangled—butchered while they slept, by vermin who had never dared to stand before them on equal terms. I, Aryara, had betrayed my trust.

Aye—I remembered. I had slept and in the midst of a dream of the hunt, fire and sparks had exploded in my head and I had plunged into a deeper darkness where there were no dreams. And now the penalty. They who had stolen through the dense forest and smitten me senseless, had not paused to mutilate me. Thinking me dead they had hastened swiftly to their grisly work. Now perhaps they had forgotten me for a time. I had sat somewhat apart from the others, and when struck, had fallen half-under some bushes. But soon they would remember me. I would hunt no more, dance no more in the dances of hunt and love and war, see no more the wattle huts of the Sword People.

But I had no wish to escape back to my people. Should I slink back with my tale of infamy and disgrace? Should I hear the words of scorn my tribe would fling at me, see the girls point their contemptuous fingers at the youth who slept and betrayed his comrades to the knives of vermin?

Tears stung my eyes, and slow hate heaved up in my bosom, and my brain. I would never bear the sword that marked the warrior. I would never triumph over worthy foes and die gloriously beneath the arrows of the Picts or the axes of the Wolf People or the River People. I would go down to death beneath a nauseous rabble, whom the Picts had long ago driven into forest dens like rats.

And mad rage gripped me and dried my tears, giving in their stead a berserk blaze of wrath. If such reptiles were to bring about my downfall, I would make it a fall long remembered—if such beasts had memories.

Moving cautiously, I shifted until my hand was on the haft of my ax; then I called on Il-marinen and bounded up as a tiger springs. And as a tiger springs I was among my enemies and mashed a flat skull as a man crushes the head of a snake. A sudden wild clamor of fear broke from my victims and for an instant they closed round me, hacking and stabbing. A knife gashed my chest but I gave no heed. A red mist waved before my eyes, and my body and limbs moved in perfect accord with my fighting brain. Snarling, hacking and smiting, I was a tiger among reptiles. In an instant they gave way and fled, leaving me bestriding half a dozen stunted bodies. But I was not satiated.

I was close on the heels of the tallest one, whose head would perhaps come to my shoulder, and who seemed to be their chief. He fled down a sort of runway, squealing like a monstrous lizard, and when I was close at his shoulder, he dived, snake-like, into the bushes. But I was too swift for him, and I dragged him forth and butchered him in a most gory fashion.

And through the bushes I saw the trail he was striving to reach—a path winding in and out among the trees, almost too narrow to allow the traversing of it by a man of normal size. I hacked off my victim’s hideous head, and carrying it in my left hand, went up the serpent-path, with my red ax in my right.

Now as I strode swiftly along the path and blood splashed beside my feet at every step from the severed jugular of my foe, I thought of those I hunted. Aye—we held them in so little esteem, we hunted by day in the forest they haunted. What they called themselves, we never knew; for none of our tribe ever learned the accursed hissing sibilances they used as speech; but we called them Children of the Night. And night-things they were indeed, for they slunk in the depths of the dark forests, and in subterraneous dwellings, venturing forth into the hills only when their conquerors slept. It was at night that they did their foul deeds—the quick flight of a flint-tipped arrow to slay cattle, or perhaps a loitering human, the snatching of a child that had wandered from the village.

But it was for more than this we gave them their name; they were, in truth, people of night and darkness and the ancient horror-ridden shadows of bygone ages. For these creatures were very old, and they represented an outworn age. They had once overrun and possessed this land, and they had been driven into hiding and obscurity by the dark, fierce little Picts with whom we contested now, and who hated and loathed them as savagely as did we.

The Picts were different from us in general appearance, being shorter of stature and dark of hair, eyes and skin, whereas we were tall and powerful, with yellow hair and light eyes. But they were cast in the same mold, for all of that. These Children of the Night seemed not human to us, with their deformed dwarfish bodies, yellow skin and hideous faces. Aye—they were reptiles—vermin.

And my brain was like to burst with fury when I thought that it was these vermin on whom I was to glut my ax and perish. Bah! There is no glory slaying snakes or dying from their bites. All this rage and fierce disappointment turned on the objects of my hatred, and with the old red mist waving in front of me I swore by all the gods I knew, to wreak such red havoc before I died as to leave a dread memory in the minds of the survivors.

My people would not honor me, in such contempt they held the Children. But those Children that I left alive would remember me and shudder. So I swore, gripping savagely my ax, which was of bronze, set in a cleft of the oaken haft and fastened securely with rawhide.

Now I heard ahead a sibilant, abhorrent murmur, and a vile stench filtered to me through the trees, human, yet less than human. A few moments more and I emerged from the deep shadows into a wide open space. I had never before seen a village of the Children. There was a cluster of earthen domes, with low doorways sunk into the ground; squalid dwelling-places, half-above and half-below the earth. And I knew from the talk of the old warriors that these dwelling-places were connected by underground corridors, so the whole village was like an ant-bed, or a system of snake holes. And I wondered if other tunnels did not run off under the ground and emerge long distances from the villages.

Before the domes clustered a vast group of the creatures, hissing and jabbering at a great rate.

I had quickened my pace, and now as I burst from cover, I was running with the fleetness of my race. A wild clamor went up from the rabble as they saw the avenger, tall, bloodstained and blazing-eyed leap from the forest, and I cried out fiercely, flung the dripping head among them and bounded like a wounded tiger into the thick of them.

Oh, there was no escape for them now! They might have taken to their tunnels but I would have followed, even to the guts of Hell. They knew they must slay me, and they closed around, a hundred strong, to do it.

There was no wild blaze of glory in my brain as there had been against worthy foes. But the old berserk madness of my race was in my blood and the smell of blood and destruction in my nostrils.

I know not how many I slew. I only know that they thronged about me in a writhing, slashing mass, like serpents about a wolf, and I smote until the ax-edge turned and bent and the ax became no more than a bludgeon; and I smashed skulls, split heads, splintered bones, scattered blood and brains in one red sacrifice to Il-marinen, god of the Sword People.

Bleeding from half a hundred wounds, blinded by a slash across the eyes, I felt a flint knife sink deep into my groin and at the same instant a cudgel laid my scalp open. I went to my knees but reeled up again, and saw in a thick red fog a ring of leering, slant-eyed faces. I lashed out as a dying tiger strikes, and the faces broke in red ruin.

And as I sagged, overbalanced by the fury of my stroke, a taloned hand clutched my throat and a flint blade was driven into my ribs and twisted venomously. Beneath a shower of blows I went down again, but the man with the knife was beneath me, and with my left hand I found him and broke his neck before he could writhe away.

Life was waning swiftly; through the hissing and howling of the Children I could hear the voice of Il-marinen. Yet once again I rose stubbornly, through a very whirlwind of cudgels and spears. I could no longer see my foes, even in a red mist. But I could feel their blows and knew they surged about me. I braced my feet, gripped my slippery ax-haft with both hands, and calling once more on Il-marinen I heaved up the ax and struck one last terrific blow. And I must have died on my feet, for there was no sensation of falling; even as I knew, with a last thrill of savagery, that slew, even as I felt the splintering of skulls beneath my ax, darkness came with oblivion.

I came suddenly to myself. I was half-reclining in a big armchair and Conrad was pouring water on me. My head ached and a trickle of blood had half-dried on my face. Kirowan, Taverel and Clemants were hovering about, anxiously, while Ketrick stood just in front of me, still holding the mallet, his face schooled to a polite perturbation which his eyes did not show. And at the sight of those cursed eyes a red madness surged up in me.

“There,” Conrad was saying, “I told you he’d come out of it in a moment; just a light crack. He’s taken harder than that. All right now, aren’t you, O’Donnel?”

At that I swept them aside, and with a single low snarl of hatred launched myself at Ketrick. Taken utterly by surprize he had no opportunity to defend himself. My hands locked on his throat and we crashed together on the ruins of a divan. The others cried out in amazement and horror and sprang to separate us—or rather, to tear me from my victim, for already Ketrick’s slant eyes were beginning to start from their sockets.

“For God’s sake, O’Donnel,” exclaimed Conrad, seeking to break my grip, “what’s come over you? Ketrick didn’t mean to hit you—let go, you idiot!”

A fierce wrath almost overcame me at these men who were my friends, men of my own tribe, and I swore at them and their blindness, as they finally managed to tear my strangling fingers from Ketrick’s throat. He sat up and choked and explored the blue marks my fingers had left, while I raged and cursed, nearly defeating the combined efforts of the four to hold me.

“You fools!” I screamed. “Let me go! Let me do my duty as a tribesman! You blind fools! I care nothing for the paltry blow he dealt me—he and his dealt stronger blows than that against me, in bygone ages. You fools, he is marked with the brand of the beast—the reptile—the vermin we exterminated centuries ago! I must crush him, stamp him out, rid the clean earth of his accursed pollution!”

So I raved and struggled and Conrad gasped to Ketrick over his shoulder: “Get out, quick! He’s out of his head! His mind is unhinged! Get away from him.”

Now I look out over the ancient dreaming downs and the hills and deep forests beyond and I ponder. Somehow, that blow from that ancient accursed mallet knocked me back into another age and another life. While I was Aryara I had no cognizance of any other life. It was no dream; it was a stray bit of reality wherein I, John O’Donnel, once lived and died, and back into which I was snatched across the voids of time and space by a chance blow. Time and times are but cogwheels, unmatched, grinding on oblivious to one another. Occasionally—oh, very rarely!—the cogs fit; the pieces of the plot snap together momentarily and give men faint glimpses beyond the veil of this everyday blindness we call reality.

I am John O’Donnel and I was Aryara, who dreamed dreams of war-glory and hunt-glory and feast-glory and who died on a red heap of his victims in some lost age. But in what age and where?

The last I can answer for you. Mountains and rivers change their contours; the landscapes alter; but the downs least of all. I look out upon them now and I remember them, not only with John O’Donnel’s eyes, but with the eyes of Aryara. They are but little changed. Only the great forest has shrunk and dwindled and in many, many places vanished utterly. But here on these very downs Aryara lived and fought and loved and in yonder forest he died. Kirowan was wrong. The little, fierce, dark Picts were not the first men in the Isles. There were beings before them—aye, the Children of the Night. Legends—why, the Children were not unknown to us when we came into what is now the isle of Britain. We had encountered them before, ages before. Already we had our myths of them. But we found them in Britain. Nor had the Picts totally exterminated them.

Nor had the Picts, as so many believe, preceded us by many centuries. We drove them before us as we came, in that long drift from the East. I, Aryara, knew old men who had marched on that century-long trek; who had been borne in the arms of yellow-haired women over countless miles of forest and plain, and who as youths had walked in the vanguard of the invaders.

As to the age—that I cannot say. But I, Aryara, was surely an Aryan and my people were Aryans—members of one of the thousand unknown and unrecorded drifts that scattered yellow-haired blue-eyed tribes all over the world. The Celts were not the first to come into western Europe. I, Aryara, was of the same blood and appearance as the men who sacked Rome, but mine was a much older strain. Of the language spoke, no echo remains in the waking mind of John O’Donnel, but I knew that Aryara’s tongue was to ancient Celtic what ancient Celtic is to modern Gaelic.

Il-marinen! I remember the god I called upon, the ancient, ancient god who worked in metals—in bronze then. For Il-marinen was one of the base gods of the Aryans from whom many gods grew; and he was Wieland and Vulcan in the ages of iron. But to Aryara he was Il-marinen.

And Aryara—he was one of many tribes and many drifts. Not alone did the Sword People come or dwell in Britain. The River People were before us and the Wolf People came later. But they were Aryans like us, light-eyed and tall and blond. We fought them, for the reason that the various drifts of Aryans have always fought each other, just as the Achaeans fought the Dorians, just as the Celts and Germans cut each other’s throats; aye, just as the Hellenes and the Persians, who were once one people and of the same drift, split in two different ways on the long trek and centuries later met and flooded Greece and Asia Minor with blood.

Now understand, all this I did not know as Aryara. I, Aryara, knew nothing of all these world-wide drifts of my race. I knew only that my people were conquerors, that a century ago my ancestors had dwelt in the great plains far to the east, plains populous with fierce, yellow-haired, light-eyed people like myself; that my ancestors had come westward in a great drift; and that in that drift, when my tribesmen met tribes of other races, they trampled and destroyed them, and when they met other yellow-haired, light-eyed people, of older or newer drifts, they fought savagely and mercilessly, according to the old, illogical custom of the Aryan people. This Aryara knew, and I, John O’Donnel, who know much more and much less than I, Aryara, knew, have combined the knowledge of these separate selves and have come to conclusions that would startle many noted scientists and historians.

Yet this fact is well known: Aryans deteriorate swiftly in sedentary and peaceful lives. Their proper existence is a nomadic one; when they settle down to an agricultural existence, they pave the way for their downfall; and when they pen themselves with city walls, they seal their doom. Why, I, Aryara, remember the tales of the old men—how the Sons of the Sword, on that long drift, found villages of white-skinned yellow-haired people who had drifted into the west centuries before and had quit the wandering life to dwell among the dark, garlic-eating people and gain their sustenance from the soil. And the old men told how soft and weak they were, and how easily they fell before the bronze blades of the Sword People.

Look—is not the whole history of the Sons of Aryan laid on those lines? Look—how swiftly has Persian followed Mede; Greek, Persian; Roman, Greek; and German, Roman. Aye, and the Norseman followed the Germanic tribes when they had grown flabby from a century or so of peace and idleness, and despoiled the spoils they had taken in the southland.

But let me speak of Ketrick. Ha—the short hairs at the back of my neck bristle at the very mention of his name. A reversion to type—but not to the type of some cleanly Chinaman or Mongol of recent times. The Danes drove his ancestors into the hills of Wales; and there, in what medieval century, and in what foul way did that cursed aboriginal taint creep into the clean Saxon blood of the Celtic line, there to lie dormant so long? The Celtic Welsh never mated with the Children any more than the Picts did. But there must have been survivals—vermin lurking in those grim hills, that had outlasted their time and age. In Aryara’s day they were scarcely human. What must a thousand years of retrogression have done to the breed?

What foul shape stole into the Ketrick castle on some forgotten night, or rose out of the dusk to grip some woman of the line, straying in the hills?

The mind shrinks from such an image. But this I know: there must have been survivals of that foul, reptilian epoch when the Ketricks went into Wales. There still may be. But this changeling, this waif of darkness, this horror who bears the noble name of Ketrick, the brand of the serpent is upon him, and until he is destroyed there is no rest for me. Now that I know him for what he is, he pollutes the clean air and leaves the slime of the snake on the green earth. The sound of his lisping, hissing voice fills me with crawling horror and the sight of his slanted eyes inspires me with madness.

For I come of a royal race, and such as he is a continual insult and a threat, like a serpent underfoot. Mine is a regal race, though now it is become degraded and falls into decay by continual admixture with conquered races. The waves of alien blood have washed my hair black and my skin dark, but I still have the lordly stature and the blue eyes of a royal Aryan.

And as my ancestors—as I, Aryara, destroyed the scum that writhed beneath our heels, so shall I, John O’Donnel, exterminate the reptilian thing, the monster bred of the snaky taint that slumbered so long unguessed in clean Saxon veins, the vestigial serpent-things left to taunt the Sons of Aryan. They say the blow I received affected my mind; I know it but opened my eyes. Mine ancient enemy walks often on the moors alone, attracted, though he may not know it, by ancestral urgings. And on one of these lonely walks I shall meet him, and when I meet him, I will break his foul neck with my hands, as I, Aryara, broke the necks of foul night-things in the long, long ago.

Then they may take me and break my neck at the end of a rope if they will. I am not blind, if my friends are. And in the sight of the old Aryan god, if not in the blinded eyes of men, I will have kept faith with my tribe.