Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

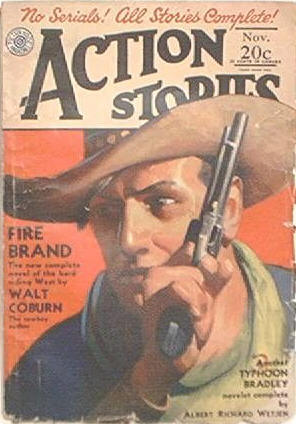

Published in Action Stories, Vol. 11, No. 3 (November 1931).

Me and my white bulldog Mike was peaceably taking our beer in a joint on the waterfront when Porkey Straus come piling in, plumb puffing with excitement.

“Hey, Steve!” he yelped. “What you think? Joe Ritchie’s in port with Terror.”

“Well?” I said.

“Well, gee whiz,” he said, “you mean to set there and let on like you don’t know nothin’ about Terror, Ritchie’s fightin’ brindle bull? Why, he’s the pit champeen of the Asiatics. He’s killed more fightin’ dogs than—”

“Yeah, yeah,” I said impatiently. “I know all about him. I been listenin’ to what a bear-cat he is for the last year, in every Asiatic port I’ve touched.”

“Well,” said Porkey, “I’m afraid we ain’t goin’ to git to see him perform.”

“Why not?” asked Johnnie Blinn, a shifty-eyed bar-keep.

“Well,” said Porkey, “they ain’t a dog in Singapore to match ag’in’ him. Fritz Steinmann, which owns the pit and runs the dog fights, has scoured the port and they just ain’t no canine which their owners’ll risk ag’in’ Terror. Just my luck. The chance of a lifetime to see the fightin’est dog of ’em all perform. And they’s no first-class mutt to toss in with him. Say, Steve, why don’t you let Mike fight him?”

“Not a chance,” I growled. “Mike gets plenty of scrappin’ on the streets. Besides, I’ll tell you straight, I think dog fightin’ for money is a dirty low-down game. Take a couple of fine, upstandin’ dogs, full of ginger and fightin’ heart, and throw ’em in a concrete pit to tear each other’s throats out, just so a bunch of four-flushin’ tin-horns like you, which couldn’t take a punch or give one either, can make a few lousy dollars bettin’ on ’em.”

“But they likes to fight,” argued Porkey. “It’s their nature.”

“It’s the nature of any red-blooded critter to fight. Man or dog!” I said. “Let ’em fight on the streets, for bones or for fun, or just to see which is the best dog. But pit-fightin’ to the death is just too dirty for me to fool with, and I ain’t goin’ to get Mike into no such mess.”

“Aw, let him alone, Porkey,” sneered Johnnie Blinn nastily. “He’s too chicken-hearted to mix in them rough games. Ain’t you, Sailor?”

“Belay that,” I roared. “You keep a civil tongue in your head, you wharfside rat. I never did like you nohow, and one more crack like that gets you this.” I brandished my huge fist at him and he turned pale and started scrubbing the bar like he was trying for a record.

“I wantcha to know that Mike can lick this Terror mutt,” I said, glaring at Porkey. “I’m fed up hearin’ fellers braggin’ on that brindle murderer. Mike can lick him. He can lick any dog in this lousy port, just like I can lick any man here. If Terror meets Mike on the street and gets fresh, he’ll get his belly-full. But Mike ain’t goin’ to get mixed up in no dirty racket like Fritz Steinmann runs and you can lay to that.” I made the last statement in a voice like a irritated bull, and smashed my fist down on the table so hard I splintered the wood, and made the decanters bounce on the bar.

“Sure, sure, Steve,” soothed Porkey, pouring hisself a drink with a shaky hand. “No offense. No offense. Well, I gotta be goin’.”

“So long,” I growled, and Porkey cruised off.

Up strolled a man which had been standing by the bar. I knowed him—Philip D’Arcy, a man whose name is well known in all parts of the world. He was a tall, slim, athletic fellow, well dressed, with bold gray eyes and a steel-trap jaw. He was one of them gentleman adventurers, as they call ’em, and he’d did everything from running a revolution in South America and flying a war plane in a Balkan brawl, to exploring in the Congo. He was deadly with a six-gun, and as dangerous as a rattler when somebody crossed him.

“That’s a fine dog you have, Costigan,” he said. “Clean white. Not a speck of any other color about him. That means good luck for his owner.”

I knowed that D’Arcy had some pet superstitions of his own, like lots of men which live by their hands and wits like him.

“Well,” I said, “anyway, he’s about the fightin’est dog you ever seen.”

“I can tell that,” he said, stooping and eying Mike close. “Powerful jaws—not too undershot—good teeth—broad between the eyes—deep chest—legs that brace like iron. Costigan, I’ll give you a hundred dollars for him, just as he stands.”

“You mean you want me to sell you Mike?” I asked kinda incredulous.

“Sure. Why not?”

“Why not!” I repeatedly indignantly. “Well, gee whiz, why not ask a man to sell his brother for a hundred dollars? Mike wouldn’t stand for it. Anyway, I wouldn’t do it.”

“I need him,” persisted D’Arcy. “A white dog with a dark man—it means luck. White dogs have always been lucky for me. And my luck’s been running against me lately. I’ll give you a hundred and fifty.”

“D’Arcy,” I said, “you couldst stand there and offer me money all day long and raise the ante every hand, but it wouldn’t be no good. Mike ain’t for sale. Him and me has knocked around the world together too long. They ain’t no use talkin’.”

His eyes flashed for a second. He didn’t like to be crossed in any way. Then he shrugged his shoulders.

“All right. We’ll forget it. I don’t blame you for thinking a lot of him. Let’s have a drink.”

So we did and he left.

I went and got me a shave, because I was matched to fight some tramp at Ace Larnigan’s Arena and I wanted to be in shape for the brawl. Well, afterwards I was walking down along the docks when I heard somebody go: “Hssst!”

I looked around and saw a yellow hand beckon me from behind a stack of crates. I sauntered over, wondering what it was all about, and there was a Chinese boy hiding there. He put his finger to his lips. Then quick he handed me a folded piece of paper, and beat it, before I couldst ask him anything.

I opened the paper and it was a note in a woman’s handwriting which read:

Dear Steve.

I have admired you for a long time at a distance, but have been too timid to make myself known to you. Would it be too much to ask you to give me an opportunity to tell you my emotions by word of mouth? If you care at all, I will meet you by the old Manchu House on the Tungen Road, just after dark.

An affectionate admirer.

P .S. Please, oh please be there! You have stole my heart away!

“Mike,” I said pensively, “ain’t it plumb peculiar the strange power I got over wimmen, even them I ain’t never seen? Here is a girl I don’t even know the name of, even, and she has been eatin’ her poor little heart out in solitude because of me. Well—” I hove a gentle sigh—“it’s a fatal gift, I’m afeared.”

Mike yawned. Sometimes it looks like he ain’t got no romance at all about him. I went back to the barber shop and had the barber to put some ile on my hair and douse me with perfume. I always like to look genteel when I meet a feminine admirer.

Then, as the evening was waxing away, as the poets say, I set forth for the narrow winding back street just off the waterfront proper. The natives call it the Tungen Road, for no particular reason as I can see. The lamps there is few and far between and generally dirty and dim. The street’s lined on both sides by lousy looking native shops and hovels. You’ll come to stretches which looks clean deserted and falling to ruins.

Well, me and Mike was passing through just such a district when I heard sounds of some kind of a fracas in a dark alley-way we was passing. Feet scruffed. They was the sound of a blow and a voice yelled in English: “Halp! Halp! These Chinese is killin’ me!”

“Hold everything,” I roared, jerking up my sleeves and plunging for the alley, with Mike at my heels. “Steve Costigan is on the job.”

It was as dark as a stack of black cats in that alley. Plunging blind, I bumped into somebody and sunk a fist to the wrist in him. He gasped and fell away. I heard Mike roar suddenly and somebody howled bloody murder. Then wham! A blackjack or something like it smashed on my skull and I went to my knees.

“That’s done yer, yer blawsted Yank,” said a nasty voice in the dark.

“You’re a liar,” I gasped, coming up blind and groggy but hitting out wild and ferocious. One of my blind licks musta connected because I heard somebody cuss bitterly. And then wham, again come that blackjack on my dome. What little light they was, was behind me, and whoever it was slugging me, couldst see me better’n I could see him. That last smash put me down for the count, and he musta hit me again as I fell.

I couldn’t of been out but a few minutes. I come to myself lying in the darkness and filth of the alley and I had a most splitting headache and dried blood was clotted on a cut in my scalp. I groped around and found a match in my pocket and struck it.

The alley was empty. The ground was all tore up and they was some blood scattered around, but neither the thugs nor Mike was nowhere to be seen. I run down the alley, but it ended in a blank stone wall. So I come back onto the Tungen Road and looked up and down but seen nobody. I went mad.

“Philip D’Arcy!” I yelled all of a sudden. “He done it. He stole Mike. He writ me that note. Unknown admirer, my eye. I been played for a sucker again. He thinks Mike’ll bring him luck. I’ll bring him luck, the double-crossin’ son-of-a-seacook. I’ll sock him so hard he’ll bite hisself in the ankle. I’ll bust him into so many pieces he’ll go through a sieve—”

With these meditations, I was running down the street at full speed, and when I busted into a crowded thoroughfare, folks turned and looked at me in amazement. But I didn’t pay no heed. I was steering my course for the European Club, a kind of ritzy place where D’Arcy generally hung out. I was still going at top-speed when I run up the broad stone steps and was stopped by a pompous looking doorman which sniffed scornfully at my appearance, with my clothes torn and dirty from laying in the alley, and my hair all touseled and dried blood on my hair and face.

“Lemme by,” I gritted, “I gotta see a mutt.”

“Gorblime,” said the doorman. “You cawn’t go in there. This is a very exclusive club, don’t you know. Only gentlemen are allowed here. Cawn’t have a blawsted gorilla like you bursting in on the gentlemen. My word! Get along now before I call the police.”

There wasn’t time to argue.

With a howl of irritation I grabbed him by the neck and heaved him into a nearby goldfish pond. Leaving him floundering and howling, I kicked the door open and rushed in. I dashed through a wide hallway and found myself in a wide room with big French winders. That seemed to be the main club room, because it was very scrumptiously furnished and had all kinds of animal heads on the walls, alongside of crossed swords and rifles in racks.

They was a number of Americans and Europeans setting around drinking whiskey-and-sodas, and playing cards. I seen Philip D’Arcy setting amongst a bunch of his club-members, evidently spinning yards about his adventures. And I seen red.

“D’Arcy!” I yelled, striding toward him regardless of the card tables I upset. “Where’s my dog?”

Philip D’Arcy sprang up with a kind of gasp and all the club men jumped up too, looking amazed.

“My word!” said a Englishman in a army officer’s uniform. “Who let this boundah in? Come, come, my man, you’ll have to get out of this.”

“You keep your nose clear of this or I’ll bend it clean outa shape,” I howled, shaking my right mauler under the aforesaid nose. “This ain’t none of your business. D’Arcy, what you done with my dog?”

“You’re drunk, Costigan,” he snapped. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“That’s a lie,” I screamed, crazy with rage. “You tried to buy Mike and then you had me slugged and him stole. I’m on to you, D’Arcy. You think because you’re a big shot and I’m just a common sailorman, you can take what you want. But you ain’t gettin’ away with it. You got Mike and you’re goin’ to give him back or I’ll tear your guts out. Where is he? Tell me before I choke it outa you.”

“Costigan, you’re mad,” snarled D’Arcy, kind of white. “Do you know whom you’re threatening? I’ve killed men for less than that.”

“You stole my dog!” I howled, so wild I hardly knowed what I was doing.

“You’re a liar,” he rasped. Blind mad, I roared and crashed my right to his jaw before he could move. He went down like a slaughtered ox and laid still, blood trickling from the corner of his mouth. I went for him to strangle him with my bare hands, but all the club men closed in between us.

“Grab him,” they yelled. “He’s killed D’Arcy. He’s drunk or crazy. Hold him until we can get the police.”

“Belay there,” I roared, backing away with both fists cocked. “Lemme see the man that’ll grab me. I’ll knock his brains down his throat. When that rat comes to, tell him I ain’t through with him, not by a dam’ sight. I’ll get him if it’s the last thing I do.”

And I stepped through one of them French winders and strode away cursing between my teeth. I walked for some time in a kind of red mist, forgetting all about the fight at Ace’s Arena, where I was already due. Then I got a idee. I was fully intending to get ahold of D’Arcy and choke the truth outa him, but they was no use trying that now. I’d catch him outside his club some time that night. Meanwhile, I thought of something else. I went into a saloon and got a big piece of white paper and a pencil, and with much labor, I printed out what I wanted to say. Then I went out and stuck it up on a wooden lamp-post where folks couldst read it. It said:

I will pay any man fifty dollars ($50) that can find my bulldog Mike which was stole by a lo-down scunk.

Steve Costigan.

I was standing there reading it to see that the words was spelled right when a loafer said: “Mike stole? Too bad, Sailor. But where you goin’ to git the fifty to pay the reward? Everybody knows you ain’t got no money.”

“That’s right,” I said. So I wrote down underneath the rest:

P. S. I am going to get fifty dollars for licking some mutt at Ace’s Areener that is where the reward money is coming from.

S. C.

I then went morosely along the street wondering where Mike was and if he was being mistreated or anything. I moped into the Arena and found Ace walking the floor and pulling his hair.

“Where you been?” he howled. “You realize you been keepin’ the crowd waitin’ a hour? Get into them ring togs.”

“Let ’em wait,” I said sourly, setting down and pulling off my shoes. “Ace, a yellow-livered son-of-a-skunk stole my dog.”

“Yeah?” said Ace, pulling out his watch and looking at it. “That’s tough, Steve. Hustle up and get into the ring, willya? The crowd’s about ready to tear the joint down.”

I climbed into my trunks and bathrobe and mosied up the aisle, paying very little attention either to the hisses or cheers which greeted my appearance. I clumb into the ring and looked around for my opponent.

“Where’s Grieson?” I asked Ace.

“ ’E ’asn’t showed up yet,” said the referee.

“Ye gods and little fishes!” howled Ace, tearing his hair. “These bone-headed leather-pushers will drive me to a early doom. Do they think a pummoter’s got nothin’ else to do but set around all night and pacify a ragin’ mob whilst they play around? These thugs is goin’ to lynch us all if we don’t start some action right away.”

“Here he comes,” said the referee as a bath-robed figger come hurrying down the aisle. Ace scowled bitterly and held up his hands to the frothing crowd.

“The long delayed main event,” he said sourly. “Over in that corner, Sailor Costigan of the Sea Girl, weight 190 pounds. The mutt crawlin’ through the ropes is ‘Limey’ Grieson, weight 189. Get goin’—and I hope you both get knocked loop-legged.”

The referee called us to the center of the ring for instructions and Grieson glared at me, trying to scare me before the scrap started—the conceited jassack. But I had other things on my mind. I merely mechanically noted that he was about my height—six feet—had a nasty sneering mouth and mean black eyes, and had been in a street fight recent. He had a bruise under one ear.

We went back to our corners and I said to the second Ace had give me: “Bonehead, you ain’t seen nothin’ of nobody with my bulldog, have you?”

“Naw, I ain’t,” he said, crawling through the ropes. “And beside. . . . Hey, look out.”

I hadn’t noticed the gong sounding and Grieson was in my corner before I knowed what was happening. I ducked a slungshot right as I turned and clinched, pushing him outa the corner before I broke. He nailed me with a hard left hook to the head and I retaliated with a left to the body, but it didn’t have much enthusiasm behind it. I had something else on my mind and my heart wasn’t in the fight. I kept unconsciously glancing over to my corner where Mike always set, and when he wasn’t there, I felt kinda lost and sick and empty.

Limey soon seen I wasn’t up to par and began forcing the fight, shooting both hands to my head. I blocked and countered very slouchily and the crowd, missing my rip-roaring attack, began to murmur. Limey got too cocky and missed a looping right that had everything he had behind it. He was wide open for a instant and I mechanically ripped a left hook under his heart that made his knees buckle, and he covered up and walked away from me in a hurry, with me following in a sluggish kind of manner.

After that he was careful, not taking many chances. He jabbed me plenty, but kept his right guard high and close in. I ignores left jabs at all times, so though he was outpointing me plenty, he wasn’t hurting me none. But he finally let go his right again and started the claret from my nose. That irritated me and I woke up and doubled him over with a left hook to the guts which wowed the crowd. But they yelled with rage and amazement when I failed to foller up. To tell the truth, I was fighting very absent-mindedly.

As I walked back to my corner at the end of the first round, the crowd was growling and muttering restlessly, and the referee said: “Fight, you blasted Yank, or I’ll throw you h’out of the ring.” That was the first time I ever got a warning like that.

“What’s the matter with you, Sailor?” said Bonehead, waving the towel industriously. “I ain’t never seen you fight this way before.”

“I’m worried about Mike,” I said. “Bonehead, where-all does Philip D’Arcy hang out besides the European Club?”

“How should I know?” he said. “Why?”

“I wanta catch him alone some place,” I growled. “I betcha—”

“There’s the gong, you mutt,” yelled Bonehead, pushing me out of my corner. “For cat’s cake, get in there and fight. I got five bucks bet on you.”

I wandered out into the middle of the ring and absent-mindedly wiped Limey’s chin with a right that dropped him on his all-fours. He bounced up without a count, clearly addled, but just as I was fixing to polish him off, I heard a racket at the door.

“Lemme in,” somebody was squalling. “I gotta see Meest Costigan. I got one fellow dog belong along him.”

“Wait a minute,” I growled to Limey, and run over to the ropes, to the astounded fury of the fans, who rose and roared.

“Let him in, Bat,” I yelled and the feller at the door hollered back: “Alright, Steve, here he comes.”

And a Chinese kid come running up the aisle grinning like all get-out, holding up a scrawny brindle bull-pup.

“Here that one fellow dog, Mees Costigan,” he yelled.

“Aw heck,” I said. “That ain’t Mike. Mike’s white. I thought everybody in Singapore knowed Mike—”

At this moment I realized that the still groggy Grieson was harassing me from the rear, so I turned around and give him my full attention for a minute. I had him backed up ag’in’ the ropes, bombarding him with lefts and rights to the head and body, when I heard Bat yell: “Here comes another’n, Steve.”

“Pardon me a minute,” I snapped to the reeling Limey, and run over to the ropes just as a grinning coolie come running up the aisle with a white dog which might of had three or four drops of bulldog blood in him.

“Me catchum, boss,” he chortled. “Heap fine white dawg. Me catchum fifty dolla?”

“You catchum a kick in the pants,” I roared with irritation. “Blame it all, that ain’t Mike.”

At this moment Grieson, which had snuck up behind me, banged me behind the ear with a right hander that made me see about a million stars. This infuriated me so I turned and hit him in the belly so hard I bent his back-bone. He curled up like a worm somebody’d stepped on and while the referee was counting over him, the gong ended the round.

They dragged Limey to his corner and started working on him. Bonehead, he said to me: “What kind of a game is this, Sailor? Gee whiz, that mutt can’t stand up to you a minute if you was tryin’. You shoulda stopped him in the first round. Hey, lookit there.”

I glanced absent-mindedly over at the opposite corner and seen that Limey’s seconds had found it necessary to take off his right glove in the process of reviving him. They was fumbling over his bare hand.

“They’re up to somethin’ crooked,” howled Bonehead. “I’m goin’ to appeal to the referee.”

“Here comes some more mutts, Steve,” bawled Bat and down the aisle come a Chinese coolie, a Jap sailor, and a Hindoo, each with a barking dog. The crowd had been seething with bewildered rage, but this seemed to somehow hit ’em in the funny bone and they begunst to whoop and yell and laugh like a passel of hyenas. The referee was roaming around the ring cussing to hisself and Ace was jumping up and down and tearing his hair.

“Is this a prize-fight or a dog-show,” he howled. “You’ve rooint my business. I’ll be the laughin’ stock of the town. I’ll sue you, Costigan.”

“Catchum fine dawg, Meest’ Costigan,” shouted the Chinese, holding up a squirming, yowling mutt which done its best to bite me.

“You deluded heathen,” I roared, “that ain’t even a bull dog. That’s a chow.”

“You clazee,” he hollered. “Him fine blull dawg.”

“Don’t listen,” said the Jap. “Him bull dog.” And he held up one of them pint-sized Boston bull-terriers.

“Not so,” squalled the Hindoo. “Here is thee dog for you, sahib. A pure blood Rampur hound. No dog can overtake him in thee race—”

“Ye gods!” I howled. “Is everybody crazy? I oughta knowed these heathens couldn’t understand my reward poster, but I thought—”

“Look out, sailor,” roared the crowd.

I hadn’t heard the gong. Grieson had slipped up on me from behind again, and I turned just in time to get nailed on the jaw by a sweeping right-hander he started from the canvas. Wham! The lights went out and I hit the canvas so hard it jolted some of my senses back into me again.

I knowed, even then, that no ordinary gloved fist had slammed me down that way. Limey’s men hadst slipped a iron knuckle-duster on his hand when they had his glove off. The referee sprung forward with a gratified yelp and begun counting over me. I writhed around, trying to get up and kill Limey, but I felt like I was done. My head was swimming, my jaw felt dead, and all the starch was gone outa my legs. They felt like they was made outa taller.

My head reeled. And I could see stars over the horizon of dogs.

“. . . Four . . .” said the referee above the yells of the crowd and the despairing howls of Bonehead, who seen his five dollars fading away. “. . . Five . . . Six . . . Seven . . .”

“There,” said Limey, stepping back with a leer. “That’s done yer, yer blawsted Yank.”

Snap! went something in my head. That voice. Them same words. Where’d I heard ’em before? In the black alley offa the Tungen Road. A wave of red fury washed all the grogginess outa me.

I forgot all about my taller legs. I come off the floor with a roar which made the ring lights dance, and lunged at the horrified Limey like a mad bull. He caught me with a straight left coming in, but I didn’t even check a instant. His arm bent and I was on top of him and sunk my right mauler so deep into his ribs I felt his heart throb under my fist. He turned green all over and crumbled to the canvas like all his bones hadst turned to butter. The dazed referee started to count, but I ripped off my gloves and pouncing on the gasping warrior, I sunk my iron fingers into his throat.

“Where’s Mike, you gutter rat?” I roared. “What’d you do with him? Tell me, or I’ll tear your windpipe out.”

“ ’Ere, ’ere,” squawked the referee. “You cawn’t do that. Let go of him, I say. Let go, you fiend.”

He got me by the shoulders and tried to pull me off. Then, seeing I wasn’t even noticing his efforts, he started kicking me in the ribs. With a wrathful beller, I rose up and caught him by the nape of the neck and the seat of the britches and throwed him clean through the ropes. Then I turned back on Limey.

“You Limehouse spawn,” I bellered. “I’ll choke the life outa you.”

“Easy, mate, easy,” he gasped, green-tinted and sick. “I’ll tell yer. We stole the mutt? Fritz Steinmann wanted him—”

“Steinmann?” I howled in amazement.

“He warnted a dorg to fight Ritchie’s Terror,” gasped Limey. “Johnnie Blinn suggested he should ’ook your Mike. Johnnie hired me and some strong-arms to turn the trick—Johnnie’s gel wrote you that note—but how’d you know I was into it—”

“I oughta thought about Blinn,” I raged. “The dirty rat. He heard me and Porkey talkin’ and got the idee. Where is Blinn?”

“Somewheres gettin’ sewed up,” gasped Grieson. “The dorg like to tore him to ribbons afore we could get the brute into the bamboo cage we had fixed.”

“Where is Mike?” I roared, shaking him till his teeth rattled.

“At Steinmann’s, fightin’ Terror,” groaned Limey. “Ow, lor’—I’m sick. I’m dyin’.”

I riz up with a maddened beller and made for my corner. The referee rose up outa the tangle of busted seats and cussing fans and shook his fist at me with fire in his eye.

“Steve Costigan,” he yelled. “You lose the blawsted fight on a foul.”

“So’s your old man,” I roared, grabbing my bathrobe from the limp and gibbering Bonehead. And just at that instant a regular bedlam bust loose at the ticket-door and Bat come down the aisle like the devil was chasing him. And in behind him come a mob of natives—coolies, ’ricksha boys, beggars, shopkeepers, boatmen and I don’t know what all—and every one of ’em had at least one dog and some had as many as three or four. Such a horde of chows, Pekineses, terriers, hounds and mongrels I never seen and they was all barking and howling and fighting.

“Meest’ Costigan,” the heathens howled, charging down the aisles: “You payum flifty dolla for dogs. We catchum.”

The crowd rose and stampeded, trompling each other in their flight and I jumped outa the ring and raced down the aisle to the back exit with the whole mob about a jump behind me. I slammed the door in their faces and rushed out onto the sidewalk, where the passers-by screeched and scattered at the sight of what I reckon they thought was a huge and much battered maniac running at large in a red bathrobe. I paid no heed to ’em.

Somebody yelled at me in a familiar voice, but I rushed out into the street and made a flying leap onto the running board of a passing taxi. I ripped the door open and yelled to the horrified driver: “Fritz Steinmann’s place on Kang Street—and if you ain’t there within three minutes I’ll break your neck.”

We went careening through the streets and purty soon the driver said: “Say, are you an escaped criminal? There’s a car followin’ us.”

“You drive,” I yelled. “I don’t care if they’s a thousand cars follerin’ us. Likely it’s a Chinaman with a pink Pomeranian he wants to sell me for a white bull dog.”

The driver stepped on it and when we pulled up in front of the innocent-looking building which was Steinmann’s secret arena, we’d left the mysterious pursuer clean outa sight. I jumped out and raced down a short flight of stairs which led from the street down to a side entrance, clearing my decks for action by shedding my bathrobe as I went. The door was shut and a burly black-jowled thug was lounging outside. His eyes narrowed with surprise as he noted my costume, but he bulged in front of me and growled: “Wait a minute, you. Where do you think you’re goin’?”

“In!” I gritted, ripping a terrible right to his unshaven jaw.

Over his prostrate carcass I launched myself bodily against the door, being in too much of a hurry to stop and see if it was unlocked. It crashed in and through its ruins I catapulted into the room.

It was a big basement. A crowd of men—the scrapings of the waterfront—was ganged about a deep pit sunk in the concrete floor from which come a low, terrible, worrying sound like dogs growling through a mask of torn flesh and bloody hair—like fighting dogs growl when they have their fangs sunk deep.

The fat Dutchman which owned the dive was just inside the door and he whirled and went white as I crashed through. He threw up his hands and screamed, just as I caught him with a clout that smashed his nose and knocked six front teeth down his throat. Somebody yelled: “Look out, boys! Here comes Costigan! He’s on the kill!”

The crowd yelled and scattered like chaff before a high wind as I come ploughing through ’em like a typhoon, slugging right and left and dropping a man at each blow. I was so crazy mad I didn’t care if I killed all of ’em. In a instant the brink of the pit was deserted as the crowd stormed through the exits, and I jumped down into the pit. Two dogs was there, a white one and a big brindle one, though they was both so bloody you couldn’t hardly tell their original color. Both had been savagely punished, but Mike’s jaws had locked in the death-hold on Terror’s throat and the brindle dog’s eyes was glazing.

Joe Ritchie was down on his knees working hard over them and his face was the color of paste. They’s only two ways you can break a bull dog’s death-grip; one is by deluging him with water till he’s half drowned and opens his mouth to breathe. The other’n is by choking him off. Ritchie was trying that, but Mike had such a bull’s neck, Joe was only hurting his fingers.

“For gosh sake, Costigan,” he gasped. “Get this white devil off. He’s killin’ Terror.”

“Sure I will,” I grunted, stooping over the dogs. “Not for your sake, but for the sake of a good game dog.” And I slapped Mike on the back and said: “Belay there, Mike; haul in your grapplin’ irons.”

Mike let go and grinned up at me with his bloody mouth, wagging his stump of a tail like all get-out and pricking up one ear. Terror had clawed the other’n to rags. Ritchie picked up the brindle bull and clumb outa the pit and I follered him with Mike.

“You take that dog to where he can get medical attention and you do it pronto,” I growled. “He’s a better man than you, any day in the week, and more fittin’ to live. Get outa my sight.”

He slunk off and Steinmann come to on the floor and seen me and crawled to the door on his all-fours before he dast to get up and run, bleeding like a stuck hawg. I was looking over Mike’s cuts and gashes, when I realized that a man was standing nearby, watching me.

I wheeled. It was Philip D’Arcy, with a blue bruise on his jaw where I’d socked him, and his right hand inside his coat.

“D’arcy,” I said, walking up to him. “I reckon I done made a mess of things. I just ain’t got no sense when I lose my temper, and I honestly thought you’d stole Mike. I ain’t much on fancy words and apologizin’ won’t do no good. But I always try to do what seems right in my blunderin’ blame-fool way, and if you wanta, you can knock my head off and I won’t raise a hand ag’in’ you.” And I stuck out my jaw for him to sock.

He took his hand outa his coat and in it was a cocked six-shooter.

“Costigan,” he said, “no man ever struck me before and got away with it. I came to Larnigan’s Arena tonight to kill you. I was waiting for you outside and when I saw you run out of the place and jump into a taxi, I followed you to do the job wherever I caught up with you. But I like you. You’re a square-shooter. And a man who thinks as much of his dog as you do is my idea of the right sort. I’m putting this gun back where it belongs—and I’m willing to shake hands and call it quits, if you are.”

“More’n willin’,” I said heartily. “You’re a real gent.” And we shook. Then all at once he started laughing.

“I saw your poster,” he said. “When I passed by, an Indian babu was translating it to a crowd of natives and he was certainly making a weird mess of it. The best he got out of it was that Steve Costigan was buying dogs at fifty dollars apiece. You’ll be hounded by canine-peddlers as long as you’re in port.”

“The Sea Girl’s due tomorrer, thank gosh,” I replied. “But right now I got to sew up some cuts on Mike.”

“My car’s outside,” said D’Arcy. “Let’s take him up to my rooms. I’ve had quite a bit of practice at such things and we’ll fix him up ship-shape.”

“It’s a dirty deal he’s had,” I growled. “And when I catch Johnnie Blinn I’m goin’ kick his ears off. But,” I added, swelling out my chest seven or eight inches, “I don’t reckon I’ll have to lick no more saps for sayin’ that Ritchie’s Terror is the champeen of all fightin’ dogs in the Asiatics. Mike and me is the fightin’est pair of scrappers in the world.”