(title ripped off)

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

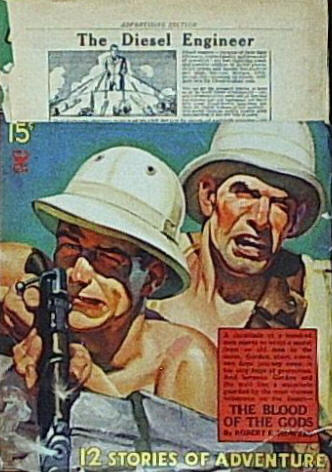

Published in Top-Notch, Vol. 97, No. 1 (July 1935).

| Chapter I. A Shot Through the Window Chapter II. The Abodes of Emptiness Chapter III. The Fight at the Well of Amir Khan |

Chapter IV. The Djinn of the Caves Chapter V. Hawks at Bay Chapter VI. The Devil of the Night |

It was the wolfish snarl on Hawkston’s thin lips, the red glare in his eyes, which first roused terrified suspicion in the Arab’s mind, there in the deserted hut on the outskirts of the little town of Azem. Suspicion became certainty as he stared at the three dark, lowering faces of the other white men, bent toward him, and all beastly with the same cruel greed that twisted their leader’s features.

The brandy glass slipped from the Arab’s hand and his swarthy skin went ashy.

“Lah!” he cried desperately. “No! You lied to me! You are not friends—you brought me here to murder me—”

He made a convulsive effort to rise, but Hawkston grasped the bosom of his gumbaz in an iron grip and forced him down into the camp chair again. The Arab cringed away from the dark, hawk-like visage bending close to his own.

“You won’t be hurt, Dirdar,” rasped the Englishman. “Not if you tell us what we want to know. You heard my question. Where is Al Wazir?”

The beady eyes of the Arab glared wildly up at his captor for an instant, then Dirdar moved with all the strength and speed of his wiry body. Bracing his feet against the floor, he heaved backward suddenly, toppling the chair over and throwing himself along with it. With a rending of worn cloth the bosom of the gumbaz came away in Hawkston’s hand, and Dirdar, regaining his feet like a bouncing rubber ball, dived straight at the open door, ducking beneath the pawing arm of the big Dutchman, Van Brock. But he tripped over Ortelli’s extended leg and fell sprawling, rolling on his back to slash up at the Italian with the curved knife he had snatched from his girdle. Ortelli jumped back, yowling, blood spurting from his leg, but as Dirdar once more bounced to his feet, the Russian, Krakovitch, struck him heavily from behind with a pistol barrel.

As the Arab sagged to the floor, stunned, Hawkston kicked the knife out of his hand. The Englishman stooped, grabbed him by the collar of his abba, and grunted: “Help me lift him, Van Brock.”

The burly Dutchman complied, and the half-senseless Arab was slammed down in the chair from which he had just escaped. They did not tie him, but Krakovitch stood behind him, one set of steely fingers digging into his shoulder, the other poising the long gun-barrel.

Hawkston poured out a glass of brandy and thrust it to his lips. Dirdar gulped mechanically, and the glassiness faded out of his eyes.

“He’s coming around,” grunted Hawkston. “You hit him hard, Krakovitch. Shut up, Ortelli! Tie a rag about your bally leg and quit grousing about it! Well, Dirdar, are you ready to talk?”

The Arab looked about like a trapped animal, his lean chest heaving under the torn gumbaz. He saw no mercy in the flinty faces about him.

“Let’s burn his cursed feet,” snarled Ortelli, busy with an improvised bandage. “Let me put the hot irons to the swine—”

Dirdar shuddered and his gaze sought the face of the Englishman, with burning intensity. He knew that Hawkston was leader of these lawless men by virtue of sharp wits and a sledge-like fist.

The Arab licked his lips.

“As Allah is my witness, I do not know where Al Wazir is!”

“You lie!” snapped the Englishman. “We know that you were one of the party that took him into the desert—and he never came back. We know you know where he was left. Now, are you going to tell?”

“El Borak will kill me!” muttered Dirdar.

“Who’s El Borak?” rumbled Van Brock.

“American,” snapped Hawkston. “Adventurer. Real name’s Gordon. He led the caravan that took Al Wazir into the desert. Dirdar, you needn’t fear El Borak. We’ll protect you from him.”

A new gleam entered the Arab’s shifty eyes; avarice mingled with the fear already there. Those beady eyes grew cunning and cruel.

“There is only one reason why you wish to find Al Wazir,” he said. “You hope to learn the secret of a treasure richer than the secret hoard of Shahrazar the Forbidden! Well, suppose I tell you? Suppose I even guide you to the spot where Al Wazir is to be found—will you protect me from El Borak—will you give me a share of the Blood of the Gods?”

Hawkston frowned, and Ortelli ripped out an oath.

“Promise the dog nothing! Burn the soles off his feet! Here! I’ll heat the irons!”

“Let that alone!” said Hawkston with an oath. “One of you better go to the door and watch. I saw that old devil Salim sneaking around through the alleys just before sundown.”

No one obeyed. They did not trust their leader. He did not repeat the command. He turned to Dirdar, in whose eyes greed was much stronger now than fear.

“How do I know you’d guide us right? Every man in that caravan swore an oath he’d never betray Al Wazir’s hiding place.”

“Oaths were made to be broken,” answered Dirdar cynically. “For a share in the Blood of the Gods I would foreswear Muhammad. But even when you have found Al Wazir, you may not be able to learn the secret of the treasure.”

“We have ways of making men talk,” Hawkston assured him grimly. “Will you put our skill to the test, or will you guide us to Al Wazir? We will give you a share of the treasure.” Hawkston had no intention of keeping his word as he spoke.

“Mashallah!” said the Arab. “He dwells alone in an all but inaccessible place. When I name it, you, at least, Hawkston effendi, will know how to reach it. But I can guide you by a shorter way, which will save two days. And a day saved on the desert is often the difference between life and death.

“Al Wazir dwells in the caves of El Khour—arrrgh!” His voice broke in a scream, and he threw up his hands, a sudden image of frantic terror, eyes glaring, teeth bared. Simultaneously the deafening report of a shot filled the hut, and Dirdar toppled from his chair, clutching at his breast. Hawkston whirled, caught a glimpse through the window of a smoking black pistol barrel and a grim bearded face. He fired at that face even as, with his left hand, he swept the candle from the table and plunged the hut into darkness.

His companions were cursing, yelling, falling over each other, but Hawkston acted with unerring decision. He plunged to the door of the hut, knocking aside somebody who stumbled into his path, and threw the door open. He saw a figure running across the road, into the shadows on the side. He threw up his revolver, fired, and saw the figure sway and fall headlong, to be swallowed up by the darkness under the trees. He crouched for an instant in the doorway, gun lifted, left arm barring the blundering rush of the other men.

“Keep back, curse you! That was old Salim. There may be more, under the trees across the road.”

But no menacing figure appeared, no sound mingled with the rustling of the palm-leaves in the wind, except a noise that might have been a man flopping in his death-throes—or dragging himself painfully away on hands and knees. This noise quickly ceased and Hawkston stepped cautiously out into the starlight. No shot greeted his appearance, and instantly he became a dynamo of energy. He leaped back into the hut, snarling: “Van Brock, take Ortelli and look for Salim. I know I hit him. You’ll probably find him lying dead over there under the trees. If he’s still breathing, finish him! He was Al Wazir’s steward. We don’t want him taking tales to Gordon.”

Followed by Krakovitch, the Englishman groped his way into the darkened hut, struck a light and held it over the prostrate figure on the floor; it etched a grey face, staring glassy eyes, and a naked breast in which showed a round blue hole from which the blood had already ceased to ooze.

“Shot through the heart!” swore Hawkston, clenching his fist. “Old Salim must have seen him with us, and trailed him, guessing what we were after. The old devil shot him to keep him from guiding us to Al Wazir—but no matter. I don’t need any guide to get me to the caves of El Khour—well?” As the Dutchman and the Italian entered.

Van Brock spoke: “We didn’t find the old dog. Smears of blood all over the grass, though. He must have been hard hit.”

“Let him go,” snarled Hawkston. “He’s crawled away to die somewhere. It’s a mile to the nearest occupied house. He won’t live to get that far. Come on! The camels and the men are ready. They’re behind that palm grove south of this hut. Everything’s ready for the jump, just as I planned it. Let’s go!”

Soon thereafter there sounded the soft pad of camel’s hoofs and the jingle of accoutrements, as a line of mounted figures, ghostly in the night, moved westward into the desert. Behind them the flat roofs of el-Azem slept in the starlight, shadowed by the palm-leaves which stirred in the breeze that blew from the Persian Gulf.

Gordon’s thumb was hooked easily in his belt, keeping his hand near the butt of his heavy pistol, as he rode leisurely through the starlight, and his gaze swept the palms which lined each side of the road, their broad fronds rattling in the faint breeze. He did not expect an ambush or the appearance of an enemy. He had no blood-feud with any man in el-Azem. And yonder, a hundred yards ahead of him, stood the flat-roofed, wall-encircled house of his friend, Achmet ibn Mitkhal, where the American was living as an honored guest. But the habits of a life-time are tenacious. For years El Borak had carried his life in his hands, and if there were hundreds of men in Arabia proud to call him friend, there were hundreds of others who would have given the teeth out of their heads for a clean sight of him, etched against the stars, over the barrel of a rifle.

Gordon reached the gate, and was about to call to the gate-keeper, when it swung open, and the portly figure of his host emerged.

“Allah be with thee, El Borak! I was beginning to fear some enemy had laid an ambush for you. Is it wise to ride alone, by night, when within a three days’ ride dwell men who bear blood-feud with you?”

Gordon swung down, and handed his reins to a groom who had followed his master out of the compound. The American was not a large man, but he was square-shouldered and deep-chested, with corded sinews and steely nerves which had been tempered and honed by the tooth-and-nail struggle for survival in the wild outlands of the world. His black eyes gleamed in the starlight like those of some untamed son of the wilderness.

“I think my enemies have decided to let me die of old age or inertia,” he replied. “There has not been—”

“What’s that?” Achmet ibn Mitkhal had his own enemies. In an instant the curious dragging, choking sounds he had heard beyond the nearest angle of the wall had transformed him into a tense image of suspicion and menace.

Gordon had heard the sounds as quickly as his Arab host, and he turned with the smooth speed of a cat, the big pistol appearing in his right hand as if by magic. He took a single quick stride toward the angle of the wall—then around that angle came a strange figure, with torn, trailing garments. A man, crawling slowly and painfully along on his hands and knees. As he crawled he gasped and panted with a grisly whistling and gagging in his breathing. As they stared at him, he slumped down almost at their feet, turning a blood-streaked visage to the starlight.

“Salim!” ejaculated Gordon softly, and with one stride he was at the angle, staring around it, pistol poised. No living thing met his eye; only an expanse of bare ground, barred by the shadows of the palms. He turned back to the prostrate man, over whom Achmet was already bending.

“Effendi!” panted the old man. “El Borak!” Gordon dropped to his knee beside him, and Salim’s bony fingers clenched desperately on his arm.

“A hakim, quick, Achmet!” snapped Gordon.

“Nay,” gasped Salim. “I am dying—”

“Who shot you, Salim?” asked Gordon, for he had already ascertained the nature of the wound which dyed the old man’s tattered abba with crimson.

“Hawkston—the Englishman.” The words came with an effort. “I saw him—the three rogues who follow him—beguiling that fool Dirdar to the deserted hut near Mekmet’s Pool. I followed for I knew—they meant no good. Dirdar was a dog. He drank liquor—like an Infidel. El Borak! He betrayed Al Wazir! In spite of his oath. I shot him—through the window—but not in time. He will never guide them—but he told Hawkston—of the caves of El Khour. I saw their caravan—camels—seven Arab servants. El Borak! They have departed—for the caves—the caves of El Khour!”

“Don’t worry about them, Salim,” replied Gordon, responding to the urgent appeal in the glazing eyes. “They’ll never lay hand on Al Wazir. I promise you.”

“Al Hamud Lillah—” whispered the old Arab, and with a spasm that brought frothy blood to his bearded lips, his grim old face set in iron lines, and he was dead before Gordon could ease his head to the ground.

The American stood up and looked down at the silent figure. Achmet came close to him and tugged his sleeve.

“Al Wazir!” murmured Achmet. “Wallah! I thought men had forgotten all about that man. It is more than a year now since he disappeared.”

“White men don’t forget—not when there’s loot in the offing,” answered Gordon sardonically. “All up and down the coast men are still looking for the Blood of the Gods—those marvelous matched rubies which were Al Wazir’s especial pride, and which disappeared when he forsook the world and went into the desert to live as a hermit, seeking the Way to Truth through meditation and self-denial.”

Achmet shivered and glanced westward where, beyond the belt of palms, the shadowy desert stretched vast and mysterious to mingle its immensity with the dimness of the starlit night.

“A hard way to seek Truth,” said Achmet, who was a lover of the soft things and the rich things of life.

“Al Wazir was a strange man,” answered Gordon. “But his servants loved him. Old Salim there, for instance. Good God, Mekmet’s Pool is more than a mile from here. Salim crawled—crawled all that way, shot through and through. He knew Hawkston would torture Al Wazir—maybe kill him. Achmet, have my racing camel saddled—”

“I’ll go with you!” exclaimed Achmet. “How many men will we need? You heard Salim—Hawkston will have at least eleven men with him—”

“We couldn’t catch him now,” answered Gordon. “He’s got too much of a start on us. His camels are hejin—racing camels—too. I’m going to the caves of El Khour, alone.”

“But—”

“They’ll go by the caravan road that leads to Riyadh; I’m going by the Well of Amir Khan.”

Achmet blenched.

“Amir Khan lies within the country of Shalan ibn Mansour, who hates you as an imam hates Shaitan the Damned!”

“Perhaps none of his tribe will be at the Well,” answered Gordon. “I’m the only Feringhi who knows of that route. If Dirdar told Hawkston about it, the Englishman couldn’t find it, without a guide. I can get to the caves a full day ahead of Hawkston. I’m going alone, because we couldn’t take enough men to whip the Ruweila if they’re on the war-path. One man has a better chance of slipping through than a score. I’m not going to fight Hawkston—not now. I’m going to warn Al Wazir. We’ll hide until Hawkston gives it up and comes back to el-Azem. Then, when he’s gone, I’ll return by the caravan road.”

Achmet shouted an order to the men who were gathering just within the gate, and they scampered to do his bidding.

“You will go disguised, at least?” he urged.

“No. It wouldn’t do any good. Until I get into Ruweila country I won’t be in any danger, and after that a disguise would be useless. The Ruweila kill and plunder every stranger they catch, whether Christian or Muhammadan.”

He strode into the compound to oversee the saddling of the white racing camel.

“I’m riding light as possible,” he said. “Speed means everything. The camel won’t need any water until we reach the Well. After that it’s not a long jump to the caves. Load on just enough food and water to last me to the Well, with economy.”

His economy was that of a true son of the desert. Neither water-skin nor food-bag was over-heavy when the two were slung on the high rear pommel. With a brief word of farewell, Gordon swung into the saddle, and at the tap of his bamboo stick, the beast lurched to its feet. “Yahh!” Another tap and it swung into motion. Men pulled wide the compound gate and stood aside, their eyes gleaming in the torchlight.

“Bismillah el rahman el rahhim!” quoth Achmet resignedly, lifting his hands in a gesture of benediction, as the camel and its rider faded into the night.

“He rides to death,” muttered a bearded Arab.

“Were it another man I should agree,” said Achmet. “But it is El Borak who rides. Yet Shalan ibn Mansour would give many horses for his head.”

The sun was swinging low over the desert, a tawny stretch of rocky soil and sand as far as Gordon could see in every direction. The solitary rider was the only visible sign of life, but Gordon’s vigilance was keen. Days and nights of hard riding lay behind him; he was coming into the Ruweila country, now, and every step he took increased his danger by that much. The Ruweila, whom he believed to be kin to the powerful Roualla of El Hamad, were true sons of Ishmael—hawks of the desert, whose hands were against every man not of their clan. To avoid their country the regular caravan road to the west swung wide to the south. This was an easy route, with wells a day’s march apart, and it passed within a day’s ride of the caves of El Khour, the catacombs which pit a low range of hills rising sheer out of the wastelands.

Few white men know of their existence, but evidently Hawkston knew of the ancient trail that turned northward from the Well of Khosru, on the caravan road. Hawkston was perforce approaching El Khour circuitously. Gordon was heading straight westward, across waterless wastes, cut by a trace so faint only an Arab or El Borak could have followed it. On that route there was but one watering place between the fringe of oases along the coast and the caves—the half-mythical Well of Amir Khan, the existence of which was a secret jealously guarded by the Bedouins.

There was no fixed habitation at the oasis, which was but a clump of palms, watered by a small spring, but frequently bands of Ruweila camped there. That was a chance he must take. He hoped they were driving their camel herds somewhere far to the north, in the heart of their country; but like true hawks, they ranged far afield, striking at the caravans and the outlying villages.

The trail he was following was so slight that few would have recognized it as such. It stretched dimly away before him over a level expanse of stone-littered ground, broken on one hand by sand dunes, on the other by a succession of low ridges. He glanced at the sun, and tapped the water-bag that swung from the saddle. There was little left, though he had practiced the grim economy of a Bedouin or a wolf. But within a few hours he would be at the Well of Amir Khan, where he would replenish his supply—though his nerves tightened at the thought of what might be waiting there for him.

Even as the thought passed through his mind, the sun struck a glint from something on the nearer of the sand dunes. The quick duck of his head was instinctive, and simultaneously there rang out the crack of a rifle and he heard the thud of the bullet into flesh. The camel leaped convulsively and came down in a headlong sprawl, shot through the heart. Gordon leaped free as it fell, rifle in hand, and in an instant was crouching behind the carcass, watching the crest of the dune over the barrel of his rifle. A strident yell greeted the fall of the camel, and another shot set the echoes barking. The bullet ploughed into the ground beside Gordon’s stiffening breastwork, and the American replied. Dust spurted into the air so near the muzzle that gleamed on the crest that it evoked a volley of lurid oaths in a choked voice.

The black glittering ring was withdrawn, and presently there rose the rapid drum of hoofs. Gordon saw a white kafieh bobbing among the dunes, and understood the Bedouin’s plan. He believed there was only one man. That man intended to circle Gordon’s position, cross the trail a few hundred yards west of him, and get on the rising ground behind the American, where his vantage-point would allow him to shoot over the bulk of the camel—for of course he knew Gordon would keep the dead beast between them. But Gordon shifted himself only enough to command the trail ahead of him, the open space the Arab must cross after leaving the dunes before he reached the protection of the ridges. Gordon rested his rifle across the stiff forelegs of the camel.

A quarter of a mile up the trail there was a sandstone rock jutting up in the skyline. Anyone crossing the trail between it and himself would be limned against it momentarily. He set his sights and drew a bead against that rock. He was betting that the Bedouin was alone, and that he would not withdraw to any great distance before making the dash across the trail.

Even as he meditated a white-clad figure burst from among the ridges and raced across the trail, bending low in the saddle and flogging his mount. It was a long shot, but Gordon’s nerves did not quiver. At the exact instant that the white-clad figure was limned against the distant rock, the American pulled the trigger. For a fleeting moment he thought he had missed; then the rider straightened convulsively, threw up two wide-sleeved arms and reeled back drunkenly. The frightened horse reared high, throwing the man heavily. In an instant the landscape showed two separate shapes where there had been one—a bundle of white sprawling on the ground, and a horse racing off southward.

Gordon lay motionless for a few minutes, too wary to expose himself. He knew the man was dead; the fall alone would have killed him. But there was a slight chance that other riders might be lurking among the sand dunes, after all.

The sun beat down savagely; vultures appeared from nowhere—black dots in the sky, swinging in great circles, lower and lower. There was no hint of movement among the ridges or the dunes.

Gordon rose and glanced down at the dead camel. His jaws set a trifle more grimly; that was all. But he realized what the killing of his steed meant. He looked westward, where the heat waves shimmered. It would be a long walk, a long, dry walk, before it ended.

Stooping, he unslung water-skin and food-bag and threw them over his shoulders. Rifle in hand he went up the trail with a steady, swinging stride that would eat up the miles and carry him for hour after hour without faltering.

When he came to the shape sprawling in the path, he set the butt of his rifle on the ground and stood looking briefly, one hand steadying the bags on his shoulders. The man he had killed was a Ruweila, right enough: one of the tall, sinewy, hawk-faced and wolf-hearted plunderers of the southern desert. Gordon’s bullet had caught him just below the arm-pit. That the man had been alone, and on a horse instead of a camel, meant that there was a larger party of his tribesmen somewhere in the vicinity. Gordon shrugged his shoulders, shifted the rifle to the crook of his arm, and moved on up the trail. The score between himself and the men of Shalan ibn Mansour was red enough, already. It might well be settled once and for all at the Well of Amir Khan.

As he swung along the trail he kept thinking of the man he was going to warn: Al Wazir, the Arabs called him, because of his former capacity with the Sultan of Oman. A Russian nobleman, in reality, wandering over the world in search of some mystical goal Gordon had never understood, just as an unquenchable thirst for adventure drove El Borak around the planet in constant wanderings. But the dreamy soul of the Slav coveted something more than material things. Al Wazir had been many things. Wealth, power, position; all had slipped through his unsatisfied fingers. He had delved deep in strange religions and philosophies, seeking the answer to the riddle of Existence, as Gordon sought the stimulation of hazard. The mysticisms of the Sufia had attracted him, and finally the ascetic mysteries of the Hindus.

A year before Al Wazir had been governor of Oman, next to the Sultan the wealthiest and most powerful man on the Pearl Coast. Without warning he had given up his position and disappeared. Only a chosen few knew that he had distributed his vast wealth among the poor, renounced all ambition and power, and gone like an ancient prophet to dwell in the desert, where, in the solitary meditation and self denial of a true ascetic, he hoped to read at last the eternal riddle of Life—as the ancient prophets read it. Gordon had accompanied him on that last journey, with the handful of faithful servants who knew their master’s intentions—old Salim among them, for between the dreamy philosopher and the hard-bitten man of action there existed a powerful tie of friendship.

But for the traitor and fool, Dirdar, Al Wazir’s secret had been well kept. Gordon knew that ever since Al Wazir’s disappearance, adventurers of every breed had been searching for him, hoping to secure possession of the treasure that the Russian had possessed in the days of his power—the wonderful collection of perfectly matched rubies, known as the Blood of the Gods, which had blazed a lurid path through Oriental history for five hundred years. These jewels had not been distributed among the poor with the rest of Al Wazir’s wealth. Gordon himself did not know what the man had done with them. Nor did the American care. Greed was not one of his faults. And Al Wazir was his friend.

The blazing sun rocked slowly down the sky, its flame turned to molten copper; it touched the desert rim, and etched against it, a crawling black tiny figure, Gordon moved grimly on, striding inexorably into the somber immensities of the Ruba al Khali—the Empty Abodes.

Etched against a white streak of dawn, motionless as figures on a tapestry, Gordon saw the clump of palms that marked the Well of Amir Khan grow up out of the fading night.

A few moments later he swore, softly. Luck, the fickle jade, was not with him this time. A faint ribbon of blue smoke curled up against the whitening sky. There were men at the Well of Amir Khan.

Gordon licked his dry lips. The water-bag that slapped against his back at each stride was flat, empty. The distance he would have covered in a matter of hours, skimming over the desert on the back of his tireless camel, he had trudged on foot, the whole night long, even though he had held a gait that few even of the desert’s sons could have maintained unbroken. Even for him, in the coolness of the night, it had been a hard trek, though his iron muscles resisted fatigue like a wolf’s.

Far to the east a low blue line lay on the horizon. It was the range of hills that held the caves of El Khour. He was still ahead of Hawkston, forging on somewhere far to the south. But the Englishman would be gaining on him at every stride. Gordon could swing wide to avoid the men at the Well, and trudge on. Trudge on, afoot, and with empty water-bag? It would be suicide. He could never reach the caves on foot and without water. Already he was bitten by the devils of thirst.

A red flame grew up in his eyes, and his dark face set in wolfish lines. Water was life in the desert; life for him and for Al Wazir. There was water at the Well, and camels. There were men, his enemies, in possession of both. If they lived, he must die. It was the law of the wolf-pack, and of the desert. He slipped the limp bags from his shoulders, cocked his rifle and went forward to kill or be killed—not for wealth, nor the love of a woman, nor an ideal, nor a dream, but for as much water as could be carried in a sheep-skin bag.

A wadi or gully broke the plain ahead of him, meandering to a point within a few hundred feet of the Well. Gordon crept toward it, taking advantage of every bit of cover. He had almost reached it, at a point a hundred yards from the Well, when a man in white kafieh and ragged abba materialized from among the palms. Discovery in the growing light was instant. The Arab yelled and fired. The bullet knocked up dust a foot from Gordon’s knee, as he crouched on the edge of the gully, and he fired back. The Arab cried out, dropped his rifle and staggered drunkenly back among the palms.

The next instant Gordon had sprung down into the gully and was moving swiftly and carefully along it, toward the point where it bent nearest the Well. He glimpsed white-clad figures flitting briefly among the trees, and then rifles began to crack viciously. Bullets sang over the gully as the men fired from behind their saddles and bales of goods, piled like a rampart among the stems of the palms. They lay in the eastern fringe of the clump; the camels, Gordon knew, were on the other side of the trees. From the volume of the firing it could not be a large party.

A rock on the edge of the gully provided cover. Gordon thrust his rifle barrel under a jutting corner of it and watched for movement among the palms. Fire spurted and a bullet whined off the rock—zingggg! Dwindling in the distance like the dry whir of a rattler. Gordon fired at the puff of smoke, and a defiant yell answered him.

His eyes were slits of black flame. A fight like this could last for days. And he could not endure a siege. He had no water; he had no time. A long march to the south the caravan of Hawkston was swinging relentlessly westward, each step carrying them nearer the caves of El Khour and the unsuspecting man who dreamed his dreams there. A few hundred feet away from Gordon there was water, and camels that would carry him swiftly to his destination; but lead-fanged wolves of the desert lay between.

Lead came at his retreat thick and fast, and vehement voices rained maledictions on him. They let him know they knew he was alone, and on foot, and probably half-mad with thirst. They howled jeers and threats. But they did not expose themselves. They were confident but wary, with the caution taught by the desert deep ingrained in them. They held the winning hand and they intended to keep it so.

An hour of this, and the sun climbing over the eastern rim, and the heat beginning—the molten, blinding heat of the southern desert. It was fierce already; later it would be a scorching hell in that unshielded gully. Gordon licked his blackened lips and staked his life and the life of Al Wazir on one desperate cast of Fate’s blind dice.

Recognizing and accepting the terrible odds against success, he raised himself high enough to expose head and one shoulder above the gully rim, firing as he did so. Three rifles cracked together and lead hummed about his ears; the bullet of one raked a white-hot line across his upper arm. Instantly Gordon cried out, the loud, agonized cry of a man hard hit, and threw his arms above the rim of the gully in the convulsive gesture of a man suddenly death-stricken. One hand held the rifle and the motion threw it out of the gully, to fall ten feet away, in plain sight of the Arabs.

An instant’s silence, in which Gordon crouched below the rim, then blood-thirsty yells echoed his cry. He dared not raise himself high enough to look, but he heard the slap-slap-slap of sandalled feet, winged by hate and blood-lust. They had fallen for his ruse. Why not? A crafty man might feign a wound and fall, but who would deliberately cast away his rifle? The thought of a Feringhi, lying helpless and badly wounded in the bottom of the gully, with a defenseless throat ready for the knife, was too much for the blood-lust of the Bedouins. Gordon held himself in iron control, until the swift feet were only a matter of yards away—then he came erect like a steel spring released, the big automatic in his hand.

As he leaped up he caught one split-second glimpse of three Arabs, halting dead in their tracks, wild-eyed at the unexpected apparition—even as he straightened, his gun was roaring. One man spun on his heel and fell in a crumpled heap, shot through the head. Another fired once, with a rifle, from the hip, without aim. An instant later he was down, with a slug through his groin and another ripping through his breast as he fell. And then Fate took a hand again—Fate in the form of a grain of sand in the mechanism of Gordon’s automatic. The gun jammed just as he threw it down on the remaining Arab.

This man had no gun; only a long knife. With a howl he wheeled and legged it back for the grove, his rags whipping on the wind of his haste. And Gordon was after him like a starving wolf. His strategy might go for nothing if the man got back among the trees, where he might have left a rifle.

The Bedouin ran like an antelope, but Gordon was so close behind him when they reached the trees, the Arab had no time to snatch up the rifle leaning against the improvised rampart. He wheeled at bay, yowling like a mad dog, and slashing with the long knife. The point tore Gordon’s shirt as the American dodged, and brought down the heavy pistol on the Arab’s head. The thick kafieh saved the man’s skull from being crushed, but his knees buckled and he went down, throwing his arms about Gordon’s waist and dragging down the white man as he fell. Somewhere on the other side of the grove the wounded man was calling down curses on El Borak.

The two men rolled on the ground, ripping and smiting like wild animals. Gordon struck once again with his gun barrel, a glancing blow that laid open the Arab’s face from eye to jaw, and then dropped the jammed pistol and caught at the arm that wielded the knife. He got a grip with his left hand on the wrist and the guard of the knife itself, and with his other hand began to fight for a throat-hold. The Arab’s ghastly, blood-smeared countenance writhed in a tortured grin of muscular strain. He knew the terrible strength that lurked in El Borak’s iron fingers, knew that if they closed on his throat they would not let go until his jugular was torn out.

He threw his body frantically from side to side, wrenching and tearing. The violence of his efforts sent both men rolling over and over, to crash against palm stems and carom against saddles and bales. Once Gordon’s head was driven hard against a tree, but the blow did not weaken him, nor did the vicious drive the Arab got in with a knee to his groin. The Bedouin grew frantic, maddened by the fingers that sought his throat, the dark face, inexorable as iron, that glared into his own. Somewhere on the other side of the grove a pistol was barking, but Gordon did not feel the tear of lead, nor hear the whistle of bullets.

With a shriek like a wounded panther’s, the Arab whirled over again, a knot of straining muscles, and his hand, thrown out to balance himself, fell on the barrel of the pistol Gordon had dropped. Quick as a flash he lifted it, just as Gordon found the hold he had been seeking, and crashed the butt down on the American’s head with every ounce of strength in his lean sinews, backed by the fear of death. A tremor ran through the American’s iron frame, and his head fell forward. And in that instant the Ruweila tore free like a wolf breaking from a trap, leaving his long knife in Gordon’s hand.

Even before Gordon’s brain cleared, his war-trained muscles were responding instinctively. As the Ruweila sprang up, he shook his head and rose more slowly, the long knife in his hand. The Arab hurled the pistol at him, and caught up the rifle which leaned against the barrier. He gripped it by the barrel with both hands and wheeled, whirling the stock above his head; but before the blow could fall Gordon struck with all the blinding speed that had earned him his name among the tribes. In under the descending butt he lunged and his knife, driven with all his strength and the momentum of his charge, plunged into the Arab’s breast and drove him back against a tree into which the blade sank a hand’s breadth deep. The Bedouin cried out, a thick, choking cry that death cut short. An instant he sagged against the haft, dead on his feet and nailed upright to the palm tree. Then his knees buckled and his weight tore the knife from the wood and he pitched into the sand.

Gordon wheeled, shaking the sweat from his eyes, glaring about for the fourth man—the wounded man. The furious fight had taken only a matter of moments. The pistol was still cracking dryly on the other side of the trees, and an animal scream of pain mingled with the reports.

With a curse Gordon caught up the Arab’s rifle and burst through the grove. The wounded man lay under the shade of the trees, propped on an elbow, and aiming his pistol, not at El Borak but at the one camel that still lived. The other three lay stretched in their blood. Gordon sprang at the man, swinging the rifle stock. He was a split-second too late. The shot cracked and the camel moaned and crumpled even as the butt fell on the lifted arm, snapping the bone like a twig. The smoking pistol fell into the sand and the Arab sank back, laughing like a ghoul.

“Now see if you can escape from the Well of Amir Khan, El Borak!” he gasped. “The riders of Shalan ibn Mansour are out! Tonight or tomorrow they will return to the Well! Will you await them here, or flee on foot to die in the desert, or be tracked down like a wolf? Ya kalb! Forgotten of God! They will hang thy skin on a palmtree! Laan abuk—!”

Lifting himself with an effort that spattered his beard with bloody foam, he spat toward Gordon, laughed croakingly and fell back, dead before his head hit the ground.

Gordon stood like a statue, staring down at the dying camels. The dead man’s vengeance was grimly characteristic of his race. Gordon lifted his head and looked long at the low blue range on the western horizon. Cheeringly the dying Arab had foretold the grim choice left him. He could wait at the Well until Shalan ibn Mansour’s wild riders returned and wiped him out by force of numbers, or he could plunge into the desert again on foot. And whether he awaited certain doom at the Well, or sought the uncertain doom of the desert, inexorably Hawkston would be marching westward, steadily cutting down the lead Gordon had had at the beginning.

But Gordon never had any doubt concerning his next move. He drank deep at the Well, and bolted some of the food the Arabs had been preparing for their breakfast. Some dried dates and crusted cheese-balls he placed in a food-bag, and he filled a water-skin from the Well. He retrieved his rifle, got the sand out of his automatic and buckled to his belt a scimitar from the girdle of one of the men he had killed. He had come into the desert intending to run and hide, not to fight. But it looked very much as if he would do much more fighting before this venture was over, and the added weight of the sword was more than balanced by the feeling of added security in the touch of the lean curved blade.

Then he slung the water-skin and food-bag over his shoulders, took up his rifle and strode out of the shadows of the grove into the molten heat of the desert day. He had not slept at all the night before. His short rest at the Well had put new life and spring into his resilient muscles, hardened and toughened by an incredibly strenuous life. But it was a long, long march to the caves of El Khour, under a searing sun. Unless some miracle occurred, he could not hope to reach them before Hawkston now. And before another sun-rise the riders of Shalan ibn Mansour might well be on his trail, in which case—but all he had ever asked of Fortune was a fighting chance.

The sun rocked its slow, torturing way up the sky and down; twilight deepened into dusk, and the desert stars winked out; and on, grimly on, plodded that solitary figure, pitting an indomitable will against the merciless immensity of thirst-haunted desolation.

The caves of El Khour pit the sheer eastern walls of a gaunt hill-range that rises like a stony backbone out of a waste of rocky plains. There is only one spring in the hills; it rises in a cave high up in the wall and curls down the steep rocky slope, a slender thread of silver, to empty into a broad shallow pool below. The sun was hanging like a blood-red ball above the western desert when Francis Xavier Gordon halted near this pool and scanned the rows of gaping cave-mouths with blood-shot eyes. He licked heat-blackened lips with a tongue from which all moisture had been baked. Yet there was still a little water in the skin on his shoulder. He had economized on that gruelling march, with the savage economy of the wilderness-bred.

It seemed a bit hard to realize he had actually reached his goal. The hills of El Khour had shimmered before him for so many miles, unreal in the heat-waves, until at last they had seemed like a mirage, a fantasy of a thirst-maddened imagination. The desert sun plays tricks even with a brain like Gordon’s. Slowly, slowly the hills had grown up before him—now he stood at the foot of the eastern-most cliff, frowning up at the tiers of caves which showed their black mouths in even rows.

Nightfall had not brought Shalan ibn Mansour’s riders swooping after the solitary wanderer, nor had dawn brought them. Again and again through the long, hot day, Gordon had halted on some rise and looked back, expecting to see the dust of the hurrying camels; but the desert had stretched empty to the horizon.

And now it seemed another miracle had taken place, for there were no signs of Hawkston and his caravan. Had they come and gone? They would have at least watered their camels at the pool; and from the utter lack of signs about it, Gordon knew that no one had camped or watered animals at the pool for many moons. No, it was indisputable, even if unexplainable. Something had delayed Hawkston and Gordon had reached the caves ahead of him after all.

The American dropped on his belly at the pool and sank his face into the cool water. He lifted his head presently, shook it like a lion shaking his mane, and leisurely washed the dust from his face and hands.

Then he rose and went toward the cliff. He had seen no sign of life, yet he knew that in one of those caves lived the man he had come to seek. He lifted his voice in a far-carrying shout.

“Al Wazir! Ho there, Al Wazir!”

“Wazirrr!” whispered the echo back from the cliff. There was no other answer. The silence was ominous. With his rifle at the ready Gordon went toward the narrow trail that wound up the rugged face of the cliff. Up this he climbed, keenly scanning the eaves. They pitted the whole wall, in even tiers—too even to be the chance work of nature. They were man-made. Thousands of years ago, in the dim dawn of pre-history they had served as dwelling-places for some race of people who were not mere savages, who nitched their caverns in the soft strata with skill and cunning. Gordon knew the caves were connected by narrow passages, and that only by this ladder-like path he was following could they be reached from below.

The path ended at a long ledge, upon which all the caves of the lower tier opened. In the largest of these Al Wazir had taken up his abode.

Gordon called again, without result. He strode into the cave, and there he halted. It was square in shape. In the back wall and in each side wall showed a narrow door-like opening. Those at the sides led into adjoining caves. That at the back let into a smaller cavern, without any other outlet. There, Gordon remembered, Al Wazir had stored the dried and tinned foods he had brought with him. He had brought no furniture, nor weapons.

In one corner of the square cave a heap of charred fragments indicated that a fire had once been built there. In one corner lay a heap of skins—Al Wazir’s bed. Nearby lay the one book Al Wazir had brought with him—The Bhagavat-Gita. But of the man himself there was no evidence.

Gordon went into the storeroom, struck a match and looked about him. The tins of food were there, though the supply was considerably depleted. But they were not stacked against the wall in neat columns as Gordon had seen them stowed under Al Wazir’s directions. They were tumbled and scattered about all over the floor, with open and empty tins among them. This was not like Al Wazir, who placed a high value on neatness and order, even in small things. The rope he had brought along to aid him in exploring the caves lay coiled in one corner.

Gordon, extremely puzzled, returned to the square cave. Here, he had fully expected to find Al Wazir sitting in tranquil meditation, or out on the ledge meditating over the sun-set desert. Where was the man?

He was certain that Al Wazir had not wandered away to perish in the desert. There was no reason for him to leave the caves. If he had simply tired of his lonely life and taken his departure, he would have taken the book that was lying on the floor, his inseparable companion. There was no blood-stain on the floor, or anything to indicate that the hermit had met a violent end. Nor did Gordon believe that any Arab, even the Ruweila, would molest the “holy man.” Anyway, if Arabs had done away with Al Wazir, they would have taken away the rope and the tins of food. And he was certain that, until Hawkston learned of it, no white man but himself had known of Al Wazir’s whereabouts.

He searched through the lower tiers of caves without avail. The sun had sunk out of sight behind the hills, whose long shadows streamed far eastward across the desert, and deepening shadows filled the caverns. The silence and the mystery began to weigh on Gordon’s nerves. He began to be irked by the feeling that unseen eyes were watching him. Men who live lives of constant peril develop certain obscure faculties or instincts to a keenness unknown to those lapped about by the securities of “civilization.” As he passed through the caves, Gordon repeatedly felt an impulse to turn suddenly, to try to surprise those eyes that seemed to be boring into his back. At last he did wheel suddenly, thumb pressing back the hammer of his rifle, eyes alert for any movement in the growing dusk. The shadowy chambers and passages stood empty before him.

Once, as he passed a dark passageway he could have sworn he heard a soft noise, like the stealthy tread of a bare, furtive foot. He stepped to the mouth of the tunnel and called, without conviction: “Is that you, Ivan?” He shivered at the silence which followed; he had not really believed it was Al Wazir. He groped his way into the tunnel, rifle poked ahead of him. Within a few yards he encountered a blank wall; there seemed to be no entrance or exit except the doorway through which he had come. And the tunnel was empty, save for himself.

He returned to the ledge before the caves, in disgust.

“Hell, am I getting jumpy?”

But a grisly thought kept recurring to him—recollection of the Bedouins’ belief that a supernatural fiend lurked in these ancient caves and devoured any human foolish enough to be caught there by night. This thought kept recurring, together with the reflection that the Orient held many secrets, which the West would laugh at, but which often proved to be grim realities. That would explain Al Wazir’s mysterious absence: if some fiendish or bestial dweller in the caves had devoured him—Gordon’s speculations revolved about a hypothetical rock-python of enormous size, dwelling for generations, perhaps centuries, in the hills—that would explain the lack of any blood-stains. Abruptly he swore: “Damn! I’m going batty. There are no snakes like that in Arabia. These caves are getting on my nerves.”

It was a fact. There was a brooding weirdness about these ancient and forgotten caverns that roused uncanny speculations in Gordon’s predominantly Celtic mind. What race had occupied them, so long ago? What wars had they witnessed, against what fierce barbarians sweeping up from the south? What cruelties and intrigues had they known, what grim rituals of worship and human sacrifice? Gordon shrugged his shoulders, wishing he had not thought of human sacrifice. The idea fitted too well with the general atmosphere of these grim caverns.

Angry at himself, he returned to the big square cavern, which, he remembered, the Arabs called Niss’rosh, The Eagle’s Nest, for some reason or other. He meant to sleep in the caves that night, partly to overcome the aversion he felt toward them, partly because he did not care to be caught down on the plain in case Hawkston or Shalan ibn Mansour arrived in the night. There was another mystery. Why had not they reached the caves, one or both of them? The desert was a breeding-place of mysteries, a twilight realm of fantasy. Al Wazir, Hawkston and Shalan ibn Mansour—had the fabled djinn of the Empty Abodes snatched them up and flown away with them, leaving him the one man alive in all the vast desert? Such whims of imagination played through his exhausted brain, as, too weary to eat, he prepared for the night.

He put a large rock in the trail, poised precariously, which anyone climbing the path in the dark would be sure to dislodge. The noise would awaken him. He stretched himself on the pile of skins, painfully aware of the stress and strain of his long trek, which had taxed even his iron frame to the utmost. He was asleep almost the instant he touched his rude bed.

It was because of this weariness of body and mind that he did not hear the velvet-footed approach of the thing that crept upon him in the darkness. He woke only when taloned fingers clenched murderously on his throat and an inhuman voice whinnied sickening triumph in his ear.

Gordon’s reflexes had been trained in a thousand battles. So now he was fighting for his life before he was awake enough to know whether it was an ape or a great serpent that had attacked him. The fierce fingers had almost crushed his throat before he had a chance to tense his neck muscles. Yet those powerful muscles, even though relaxed, had saved his life. Even so the attack was so stunning, the grasp so nearly fatal, that as they rolled over the floor Gordon wasted precious seconds trying to tear away the strangling hands by wrenching at the wrists. Then as his fighting brain asserted itself, even through the red, thickening mists that were enfolding him, he shifted his tactics, drove a savage knee into a hard-muscled belly, and getting his thumbs under the little finger of each crushing hand, bent them fiercely back. No strength can resist that leverage. The unknown attacker let go, and instantly Gordon smashed a trip-hammer blow against the side of his head and rolled clear as the hard frame went momentarily limp. It was as dark in the cave as the gullet of Hell, so dark Gordon could not even see his antagonist.

He sprang to his feet, drawing his scimitar. He stood poised, tense, wondering uncomfortably if the thing could see in the dark, and scarcely breathing as he strained his ears. At the first faint sound he sprang like a panther, and slashed murderously at the noise. The blade cut only empty air, there was an incoherent cry, a shuffle of feet, then the rapidly receding pad of hurried footsteps. Whatever it was, it was in retreat. Gordon tried to follow it, ran into a blank wall, and by the time he had located the side door through which, apparently, the creature had fled, the sounds had faded out. The American struck a match and glared around, not expecting to see anything that would give him a clue to the mystery. Nor did he. The rock floor of the cavern showed no footprint.

What manner of creature he had fought in the dark he did not know. Its body had not seemed hairy enough for an ape, though the head had been a tangled mass of hair. Yet it had not fought like a human being; he had felt its talons and teeth, and it was hard to believe that human muscles could have contained such iron strength as he had encountered. And the noises it had made had certainly not resembled the sounds a man makes, even in combat.

Gordon picked up his rifle and went out on the ledge. From the position of the stars, it was past midnight. He sat down on the ledge, with his back against the cliff wall. He did not intend to sleep, but he slept in spite of himself, and woke suddenly, to find himself on his feet, with every nerve tingling, and his skin crawling with the sensation that grim peril had crept close upon him.

Even as he wondered if a bad dream had awakened him, he glimpsed a vague shadow fading into the black mouth of a cave not far away. He threw up his rifle and the shot sent the echoes flying and ringing from cliff to cliff. He waited tensely, but neither saw nor heard anything else.

After that he sat with his rifle across his knees, every faculty alert. His position, he realized, was precarious. He was like a man marooned on a deserted island. It was a day’s hard ride to the caravan road to the south. On foot it would take longer. He could reach it, unhindered—but unless Hawkston had abandoned the quest, which was not likely, the Englishman’s caravan was moving along that road somewhere. If Gordon met it, alone and on foot—Gordon had no illusions about Hawkston. But there was still a greater danger: Shalan ibn Mansour. He did not know why the shaykh had not tracked him down already, but it was certain that Shalan, scouring the desert to find the man who slew his warriors at the Well of Amir Khan, would eventually run him down. When that happened, Gordon did not wish to be caught out on the desert, on foot. Here, in the caves, with water, food and shelter, he would have at least a fighting chance. If Hawkston and Shalan should chance to arrive at the same time—that offered possibilities. Gordon was a fighting man who depended on his wits as much as his sword, and he had set his enemies tearing at each other before now. But there was a present menace to him, in the caves themselves, a menace he felt was the solution to the riddle of Al Wazir’s fate. That menace he meant to drive to bay with the coming of daylight.

He sat there until dawn turned the eastern sky rose and white. With the coming of the light he strained his eyes into the desert, expecting to see a moving line of dots that would mean men on camels. But only the tawny, empty waste levels and ridges met his gaze. Not until the sun was rising did he enter the caves; the level beams struck into them, disclosing features that had been veiled in shadows the evening before.

He went first to the passage where he had first heard the sinister footfalls, and there he found the explanation to one mystery. A series of hand and foot holds, lightly nitched in the stone of the wall, led up through a square hole in the rocky ceiling into the cave above. The djinn of the caves had been in that passage, and had escaped by that route, for some reason choosing flight rather than battle just then.

Now that he was rested, he became aware of the bite of hunger, and headed for The Eagle’s Nest, to get his breakfast out of the tins before he pursued his exploration of the caves. He entered the wide chamber, lighted by the early sun which streamed through the door—and stopped dead.

A bent figure in the door of the store-room wheeled erect, to face him. For an instant they both stood frozen. Gordon saw a man confronting him like an image of the primordial—naked, gaunt, with a great matted tangle of hair and beard, from which the eyes blazed weirdly. It might have been a caveman out of the dawn centuries who stood there, a stone gripped in each brawny hand. But the high, broad forehead, half hidden under the thatch of hair, was not the slanting brow of a savage. Nor was the face, almost covered though it was by the tangled beard.

“Ivan!” ejaculated Gordon aghast, and the explanation of the mystery rushed upon him, with all its sickening implications. Al Wazir was a madman.

As if goaded by the sound of his voice, the naked man started violently, cried out incoherently, and hurled the rock in his right hand. Gordon dodged and it shattered on the wall behind him with an impact that warned him of the unnatural power lurking in the maniac’s thews. Al Wazir was taller than Gordon, with a magnificent, broad-shouldered, lean-hipped torso, ridged with muscles. Gordon half turned and set his rifle against the wall, and as he did so, Al Wazir hurled the rock in his left hand, awkwardly, and followed it across the cave with a bound, shrieking frightfully, foam flying from his lips.

Gordon met him breast to breast, bracing his muscular legs against the impact, and Al Wazir grunted explosively as he was stopped dead in his tracks. Gordon pinioned his arms at his side, and a wild shriek broke from the madman’s lips as he tore and plunged like a trapped animal. His muscles were like quivering steel wires under Gordon’s grasp, that writhed and knotted. His teeth snapped beast-like at Gordon’s throat, and as the American jerked back his head to escape them, Al Wazir tore loose his right arm, and whipped it over Gordon’s left arm and down. Before the American could prevent it, he had grasped the scimitar hilt and torn the blade from its scabbard. Up and back went the long arm, with the sheen of naked steel, and Gordon, sensing death in the lifted sword, smashed his left fist to the madman’s jaw. It was a short terrific hook that traveled little more than a foot, but it was like the jolt of a mule’s kick.

Al Wazir’s head snapped back between his shoulders under the impact, then fell limply forward on his breast. His legs gave way simultaneously and Gordon caught him and eased him to the rocky floor.

Leaving the limp form where it lay, Gordon went hurriedly into the store-room and secured the rope. Returning to the senseless man he knotted it about his waist, then lifted him to a sitting position against a natural stone pillar at the back of the cave, passed the rope about the column and tied it with an intricate knot on the other side. The rope was too strong, even for the superhuman strength of a maniac, and Al Wazir could not reach backward around the pillar to reach and untie the knot. Then Gordon set to work reviving the man—no light task, for El Borak, with the peril of death upon him, had struck hard, with the drive and snap of steel-trap muscles. Only the heavy beard had saved the jawbone from fracture.

But presently the eyes opened and gazed wildly around, flaring redly as they fixed on Gordon’s face. The clawing hands with their long black nails, came up and caught at Gordon’s throat, as the American drew back out of reach. Al Wazir made a convulsive effort to rise, then sank back and crouched, with his unwinking stare, his fingers making aimless motions. Gordon looked at him somberly, sick at his soul. What a miserable, revolting end to dreams and philosophies! Al Wazir had come into the desert seeking meditation and peace and the visions of the ancient prophets; he had found horror and insanity. Gordon had come looking for a hermit-philosopher, radiant with mellow wisdom; he had found a filthy, naked madman.

The American filled an empty tin with water and set it, with an opened tin of meat, near Al Wazir’s hand. An instant later he dodged, as the mad hermit hurled the tins at him with all his power. Shaking his head in despair, Gordon went into the store-room and broke his own fast. He had little heart to eat, with the ruin of that once-splendid personality before him, but the urgings of hunger would not be denied.

It was while thus employed that a sudden noise outside brought him to his feet, galvanized by the imminence of danger.

It was the rattling fall of the stone Gordon had placed in the path that had alarmed him. Someone was climbing up the winding trail! Snatching up his rifle he glided out on the ledge. One of his enemies had come at last.

Down at the pool a weary, dusty camel was drinking. On the path, a few feet below the ledge there stood a tall, wiry man in dust-stained boots and breeches, his torn shirt revealing his brown, muscular chest.

“Gordon!” this man ejaculated, staring amazedly into the black muzzle of the American’s rifle. “How the devil did you get here?” His hands were empty, resting on an outcropping of rock, just as he had halted in the act of climbing. His rifle was slung to his back, pistol and scimitar in their scabbards at his belt.

“Put up your hands, Hawkston,” ordered Gordon, and the Englishman obeyed.

“What are you doing here?” he repeated. “I left you in el-Azem—”

“Salim lived long enough to tell me what he saw in the hut by Mekmet’s Pool. I came by a road you know nothing about. Where are the other jackals?”

Hawkston shook the sweat-beads from his sun-burnt forehead. He was above medium height, brown, hard as sole-leather, with a dark hawk-like face and a high-bridged predatory nose arching over a thin black mustache. A lawless adventurer, his scintillant grey eyes reflected a ruthless and reckless nature, and as a fighting man he was as notorious as was Gordon—more notorious in Arabia, for Afghanistan had been the stage for most of El Borak’s exploits.

“My men? Dead by now, I fancy. The Ruweila are on the war-path. Shalan ibn Mansour caught us at Sulaymen’s Well, with fifty men. We made a barricade of our saddles among the palms and stood them off all day. Van Brock and three of our camel-drivers were killed during the fighting, and Krakovitch was wounded. That night I took a camel and cleared out. I knew it was no use hanging on.”

“You swine,” said Gordon without passion. He did not call Hawkston a coward. He knew that not cowardice, but a cynical determination to save his skin at all hazards had driven the Englishman to desert his wounded and beleaguered companions.

“There wasn’t any use for us all to be killed,” retorted Hawkston. “I believed one man could sneak away in the dark and I did. They rushed the camp just as I got clear. I heard them killing the others. Ortelli howled like a lost soul when they cut his throat—I knew they’d run me down long before I could reach the Coast, so I headed for the caves—northwest across the open desert, leaving the road and Khosru’s Well off to the south. It was a long, dry ride, and I made it more by luck than anything else. And now can I put my hands down?”

“You might as well,” replied Gordon, the rifle at his shoulder never wavering. “In a few seconds it won’t matter much to you where your hands are.”

Hawkston’s expression did not change. He lowered his hands, but kept them away from his belt.

“You mean to kill me?” he asked calmly.

“You murdered my friend Salim. You came here to torture and rob Al Wazir. You’d kill me if you got the chance. I’d be a fool to let you live.”

“Are you going to shoot me in cold blood?”

“No. Climb up on the ledge. I’ll give you any kind of an even break you want.”

Hawkston complied, and a few seconds later stood facing the American. An observer would have been struck by a certain similarity between the two men. There was no facial resemblance, but both were burned dark by the sun, both were built with the hard economy of rawhide and spring steel, and both wore the keen, hawk-like aspect which is the common brand of men who live by their wits and guts out on the raw edges of the world.

Hawkston stood with his empty hands at his sides while Gordon faced him with rifle held hip-low, but covering his midriff.

“Rifles, pistols or swords?” asked the American. “They say you can handle a blade.”

“Second to none in Arabia,” answered Hawkston confidently. “But I’m not going to fight you, Gordon.”

“You will!” A red flame began to smolder in the black eyes. “I know you, Hawkston. You’ve got a slick tongue, and you’re treacherous as a snake. We’ll settle this thing here and now. Choose your weapons—or by God, I’ll shoot you down in your tracks!”

Hawkston shook his head calmly.

“You wouldn’t shoot a man in cold blood, Gordon. I’m not going to fight you—yet. Listen, man, we’ll have plenty of fighting on our hands before long! Where’s Al Wazir?”

“That’s none of your business,” growled Gordon.

“Well, no matter. You know why I’m here. And I know you came here to stop me if you could. But just now you and I are in the same boat. Shalan ibn Mansour’s on my trail. I slipped through his fingers, as I said, but he picked up my tracks and was after me within a matter of hours. His camels were faster and fresher than mine, and he’s been slowly overhauling me. When I topped the tallest of those ridges to the south there, I saw his dust. He’ll be here within the next hour! He hates you as much as he does me.

“You need my help, and I need yours. With Al Wazir to help us, we can hold these caves indefinitely.”

Gordon frowned. Hawkston’s tale sounded plausible, and would explain why Shalan ibn Mansour had not come hot on the American’s trail, and why the Englishman had not arrived at the caves sooner. But Hawkston was such a snake-tongued liar it was dangerous to trust him. The merciless creed of the desert said shoot him down without any more parley, and take his camel. Rested, it would carry Gordon and Al Wazir out of the desert. But Hawkston had gauged Gordon’s character correctly when he said the American could not shoot a man in cold blood.

“Don’t move,” Gordon warned him, and holding the cocked rifle like a pistol in one hand, he disarmed Hawkston, and ran a hand over him to see that he had no concealed weapons. If his scruples prevented him shooting his enemy, he was determined not to give that enemy a chance to get the drop on him. For he knew Hawkston had no such scruples.

“How do I know you’re not lying?” he demanded.

“Would I have come here alone, on a worn-out camel, if I wasn’t telling the truth?” countered Hawkston. “We’d better hide that camel, if we can. If we should beat them off, we’ll need it to get to the Coast on. Damn it, Gordon, your suspicion and hesitation will get our throats cut yet! Where’s Al Wazir?”

“Turn and look into that cave,” replied Gordon grimly.

Hawkston, his face suddenly sharp with suspicion, obeyed. As his eyes rested on the figure crouched against the column at the back of the cavern, his breath sucked in sharply.

“Al Wazir! What in God’s name’s the matter with him?”

“Too much loneliness, I reckon,” growled Gordon. “He’s stark mad. He couldn’t tell you where to find the Blood of the Gods if you tortured him all day.”

“Well, it doesn’t matter much just now,” muttered Hawkston callously. “Can’t think of treasure when life itself is at stake. Gordon, you’d better believe me! We should be preparing for a siege, not standing here chinning. If Shalan ibn Mansour—look!” He started violently, his long arm stabbing toward the south.

Gordon did not turn at the exclamation. He stepped back instead, out of the Englishman’s reach, and still covering the man, shifted his position so he could watch both Hawkston and the point of the compass indicated. Southeastward the country was undulating, broken by barren ridges. Over the farthest ridge a string of white dots was pouring, and a faint dust-haze billowed up in the air. Men on camels! A regular horde of them.

“The Ruweila!” exclaimed Hawkston. “They’ll be here within the hour!”

“They may be men of yours,” answered Gordon, too wary to accept anything not fully proven. Hawkston was as tricky as a fox, and to make a mistake on the desert meant death. “We’ll hide that camel, though, just on the chance you’re telling the truth. Go ahead of me down the trail.”

Paying no attention to the Englishman’s profanity, Gordon herded him down the path to the pool. Hawkston took the camel’s rope and went ahead leading it, under Gordon’s guidance. A few hundred yards north of the pool there was a narrow canyon winding deep into a break of the hills, and a short distance up this ravine Gordon showed Hawkston a narrow cleft in the wall, concealed behind a jutting boulder. Through this the camel was squeezed, into a natural pocket, open at the top, roughly round in shape, and about forty feet across.

“I don’t know whether the Arabs know about this place or not,” said Gordon. “But we’ll have to take the chance that they won’t find the beast.”

Hawkston was nervous.

“For God’s sake let’s get back to the caves! They’re coming like the wind. If they catch us in the open they’ll shoot us like rabbits!”

He started back at a run, and Gordon was close on his heels. But Hawkston’s nervousness was justified. The white men had not quite reached the foot of the trail that led up to the caves when a low thunder of hoofs rose on their ears, and over the nearest ridge came a wild white-clad figure on a camel, waving a rifle. At the sight of them he yelled stridently and flogged his beast into a more furious gallop, and threw his rifle to his shoulder. Behind him man after man topped the ridge—Bedouins on hejin—white racing camels.

“Up the cliff, man!” yelled Hawkston, pale under his bronze. Gordon was already racing up the path, and behind him Hawkston panted and cursed, urging greater haste, where more speed was impossible. Bullets began to snick against the cliff, and the foremost rider howled in blood-thirsty glee as he bore down swiftly upon them. He was many yards ahead of his companions, and he was a remarkable marksman, for an Arab. Firing from the rocking, swaying saddle, he was clipping his targets close.

Hawkston yelped as he was stung by a flying sliver of rock, flaked off by a smashing slug.

“Damn you, Gordon!” he panted. “This is your fault—your bloody stubbornness—he’ll pick us off like rabbits—”

The oncoming rider was not more than three hundred yards from the foot of the cliff, and the rim of the ledge was ten feet above the climbers. Gordon wheeled suddenly, threw his rifle to his shoulder and fired all in one motion, so quickly he did not even seem to take aim. But the Arab went out of his saddle like a man hit by lightning. Without pausing to note the result of his shot, Gordon raced on up the path, and an instant later he swarmed over the ledge, with Hawkston at his heels.

“Damndest snap-shot I ever saw!” gasped the Englishman.

“There’s your guns,” grunted Gordon, throwing himself flat on the ledge. “Here they come!”

Hawkston snatched his weapons from the rock where Gordon had left them, and followed the American’s example.

The Arabs had not paused. They greeted the fall of their reckless leader with yells of hate, but they flogged their mounts and came on in a headlong rush. They meant to spring off at the foot of the trail and charge up it on foot. There were at least fifty of them.

The two men lying prone on the ledge above did not lose their heads. Veterans, both of them, of a thousand wild battles, they waited coolly until the first of the riders were within good range. Then they began firing, without haste and without error. And at each shot a man tumbled headlong from his saddle or slumped forward on his mount’s bobbing neck.

Not even Bedouins could charge into such a blast of destruction. The rush wavered, split, turned on itself—and in an instant the white-clad riders were turning their backs on the caves and flogging in the other direction as madly as they had come. Five of them would never charge again, and as they fled Hawkston drilled one of the rearmost men neatly between the shoulders.

They fell back beyond the first low, stone-littered ridge, and Hawkston shook his rifle at them and cursed them with virile eloquence.

“Desert scum! Try it again, you bounders!”

Gordon wasted no breath on words. Hawkston had told the truth, and Gordon knew he was in no danger from treachery from that source, for the present. Hawkston would not attack him as long as they were confronted by a common enemy—but he knew that the instant that peril was removed, the Englishman might shoot him in the back, if he could. Their position was bad, but it might well have been worse. The Bedouins were all seasoned desert-fighters, cruel as wolves. Their chief had a blood-feud with both white men, and would not fail to grasp the chance that had thrown them into his reach. But the defenders had the advantage of shelter, an inexhaustible water supply, and food enough to last for months. Their only weakness was the limited amount of ammunition.

Without consulting one another, they took their stations on the ledge, Hawkston to the north of the trailhead, Gordon about an equal distance to the south of it.

There was no need for a conference; each man knew the other knew his business. They lay prone, gathering broken rocks in heaps before them to add to the protection offered by the ledge-rim.

Spurts of flame began to crown the ridge; bullets whined and splatted against the rock. Men crept from each end of the ridge into the clusters of boulders that littered the plain. The men on the ledge held their fire, unmoved by the slugs that whistled and spanged near at hand. Their minds worked so similarly in a situation like this that they understood each other without the necessity of conversation. There was no chance of them wasting two cartridges on the same man. An imaginary line, running from the foot of the trail to the ridge, divided their territories. When a turbaned head was poked from a rock north of that line, it was Hawkston’s rifle that knocked the man dead and sprawling over the boulder. And when a Bedouin darted from behind a spur of rock south of that line in a weaving, dodging run for cover nearer the cliff, Hawkston held his fire. Gordon’s rifle cracked and the runner took the earth in a rolling tumble that ended in a brief thrashing of limbs.

A voice rose from the ridge, edged with fury.

“That’s Shalan, damn him!” snarled Hawkston. “Can you make out what he says?”

“He’s telling his men to keep out of sight,” answered Gordon. “He tells them to be patient—they’ve got plenty of time.”

“And that’s the truth, too,” grunted Hawkston. “They’ve got time, food, water—they’ll be sneaking to the pool after dark to fill their water-skins. I wish one of us could get a clean shot at Shalan. But he’s too foxy to give us a chance at him. I saw him when they were charging us, standing back on the ridge, too far away to risk a bullet on him.”

“If we could drop him the rest of them wouldn’t hang around here a minute,” commented Gordon. “They’re afraid of the man-eating djinn they think haunts these hills.”

“Well, if they could get a good look at Al Wazir now, they’d swear it was the djinn in person,” said Hawkston. “How many cartridges have you?”

“Both guns are full, about a dozen extra rifle cartridges.”

Hawkston swore.

“I haven’t many more than that, myself. We’d better toss a coin to see which one of us sneaks out tonight, while the other keeps up a fusilade to distract their attention. The one who stays gets both rifles and all the ammunition.”

“We will like hell,” growled Gordon. “If we can’t all go, Al Wazir with us, nobody goes!”

“You’re crazy to think of a lunatic at a time like this!”

“Maybe. But if you try to sneak off I’ll drill you in the back as you run.”

Hawkston snarled wordlessly and fell silent. Both men lay motionless as red Indians, watching the ridge and the rocks that shimmered in the heat waves. The firing had ceased, but they had glimpses of white garments from time to time among the gullies and stones, as the besiegers crept about among the boulders. Some distance to the south Gordon saw a group creeping along a shallow gully that ran to the foot of the cliff. He did not waste lead on them. When they reached the cliff at that point they would be no better off. They were too far away for effective shooting, and the cliff could be climbed only at the point where the trail wound upward. Gordon fell to studying the hill that was serving the white men as their fortress.

Some thirty caves formed the lower tier, extending across the curtain of rock that formed the face of the cliff. As he knew, each cave was connected by a narrow passage to the adjoining chamber. There were three tiers above this one, all the tiers connected by ladders of hand-holds nitched in the rock, mounting from the lower caves through holes in the stone ceiling to the ones above. The Eagle’s Nest, in which Al Wazir was tied, safe from flying lead, was approximately in the middle of the lower tier, and the path hewn in the rock came upon the ledge directly before its opening. Hawkston was lying in front of the third cave to the north of it, and Gordon lay before the third cave to the south.

The Arabs lay in a wide semi-circle, extending from the rocks at one end of the low ridge, along its crest, and into the rocks at the other end. Only those lying among the rocks were close enough to do any damage, save by accident. And looking up at the ledge from below, they could see only the gleaming muzzles of the white men’s rifles, or catch fleeting glimpses of their heads occasionally. They seemed to be weary of wasting lead on such difficult targets. Not a shot had been fired for some time.

Gordon found himself wondering if a man on the crest of the cliff above the caves could, looking down, see him and Hawkston lying on the ledge. He studied the wall above him; it was almost sheer, but other, narrower ledges ran along each tier of caves, obstructing the view from above, as it did from the lower ledge. Remembering the craggy sides of the hill, Gordon did not believe these plains-dwellers would be able to scale it at any point.

He was just contemplating returning to The Eagle’s Nest to offer food and water again to Al Wazir, when a faint sound reached his ears that caused him to go tense with suspicion.

It seemed to come from the caves behind him. He glanced at Hawkston. The Englishman was squinting along his rifle barrel, trying to get a bead on a kafieh that kept bobbing in and out among the boulders near the end of the ridge.

Gordon wriggled back from the ledge-rim and rolled into the mouth of the nearest cave before he stood up, out of sight of the men below. He stood still, straining his ears.

There it was again—soft and furtive, like the rustle of cloth against stone, the shuffle of bare feet. It came from some point south of where he stood. Gordon moved silently in that direction, passed through the adjoining chamber, entered the next—and came face to face with a tall, bearded Bedouin who yelled and whirled up a scimitar. Another raider, a man with an evil, scarred face, was directly behind him, and three more were crawling out of a cleft in the floor.