Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

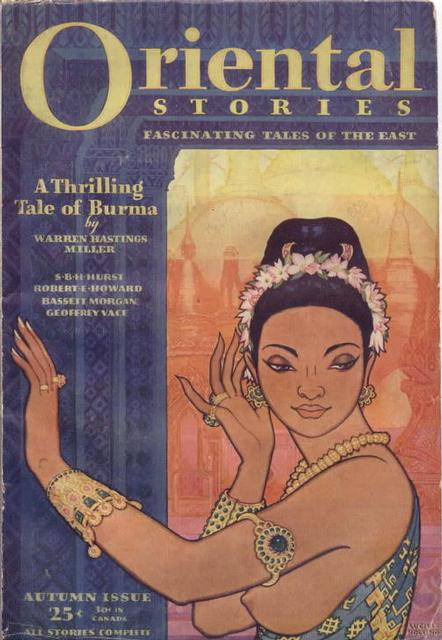

Published in Oriental Stories, Vol. 1, No. 6 (Fall 1931).

| Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 |

It shone on the breast of the Persian king.

It lighted Iskander’s road;

It blazed where the spears were splintering.

A lure and a maddening goad.

And down through the crimson, changing years

It draws men, soul and brain;

They drown their lives in blood and tears.

And they break their hearts in vain.

Oh, it flames with the blood of strong men’s hearts

Whose bodies are clay again.

—The Song of the Red Stone.

Once it was called Eski-Hissar, the Old Castle, for it was very ancient even when the first Seljuks swept out of the east, and not even the Arabs, who rebuilt that crumbling pile in the days of Abu Bekr, knew what hands reared those massive bastions among the frowning foothills of the Taurus. Now, since the old keep had become a bandit’s hold, men called it Bab-el-Shaitan, the Gate of the Devil, and with good reason.

That night there was feasting in the great hall. Heavy tables loaded with wine pitchers and jugs, and huge platters of food, stood flanked by crude benches for such as ate in that manner, while on the floor large cushions received the reclining forms of others. Trembling slaves hastened about, filling goblets from wineskins and bearing great joints of roasted meat and loaves of bread.

Here luxury and nakedness met, the riches of degenerate civilizations and the stark savagery of utter barbarism. Men clad in stenching sheepskins lolled on silken cushions, exquisitely brocaded, and guzzled from solid golden goblets, fragile as the stem of a desert flower. They wiped their bearded lips and hairy hands on velvet tapestries worthy of a shah’s palace.

All the races of western Asia met here. Here were slim, lethal Persians, dangerous-eyed Turks in mail shirts, lean Arabs, tall ragged Kurds, Lurs and Armenians in sweaty sheepskins, fiercely mustached Circassians, even a few Georgians, with hawk-faces and devilish tempers.

Among them was one who stood out boldly from all the rest. He sat at a table drinking wine from a huge goblet, and the eyes of the others strayed to him continually. Among these tall sons of the desert and mountains his height did not seem particularly great, though it was above six feet. But the breadth and thickness of him were gigantic. His shoulders were broader, his limbs more massive than any other warrior there.

His mail coif was thrown back, revealing a lion-like head and a great corded throat. Though browned by the sun, his face was not as dark as those about him and his eyes were a volcanic blue, which smoldered continually as if from inner fires of wrath. Square-cut black hair like a lion’s mane crowned a low, broad forehead.

He ate and drank apparently oblivious to the questioning glances flung toward him. Not that any had as yet challenged his right to feast in Bab-el-Shaitan, for this was a lair open to all refugees and outlaws. And this Frank was Cormac FitzGeoffrey, outlawed and hunted by his own race. The ex-Crusader was armed in close-meshed chain mail from head to foot. A heavy sword hung at his hip, and his kite-shaped shield with the grinning skull wrought in the center lay with his heavy vizorless helmet, on the bench beside him. There was no hypocrisy of etiquette in Bab-el-Shaitan. Its occupants went armed to the teeth at all times and no one questioned another’s right to sit down to meat with his sword at hand.

Cormac, as he ate, scanned his fellow-feasters openly. Truly Bab-el-Shaitan was a lair of the spawn of Hell, the last retreat of men so desperate and bestial that the rest of the world had cast them out in horror. Cormac was no stranger to savage men; in his native Ireland he had sat among barbaric figures in the gatherings of chiefs and reavers in the hills. But the wild-beast appearance and utter inhumanness of some of these men impressed even the fierce Irish warrior.

There, for instance, was a Lur, hairy as an ape, tearing at a half-raw joint of meat with yellow fangs like a wolf’s. Kadra Muhammad, the fellow’s name was, and Cormac wondered briefly if such a creature could have a human soul. Or that shaggy Kurd beside him, whose lip, twisted back by a sword scar into a permanent snarl, bared a tooth like a boar’s tusk. Surely no divine spark of soul-dust animated these men, but the merciless and soulless spirit of the grim land that bred them. Eyes, wild and cruel as the eyes of wolves, glared through lank strands of tangled hair, hairy hands unconsciously gripped the hilts of knives even while the owners gorged and guzzled.

Cormac glanced from the rank and file to scrutinize the leaders of the band—those whom superior wit or war-skill had placed high in the confidence of their terrible chief, Skol Abdhur, the Butcher. Not one but had a whole volume of black and bloody history behind him. There was that slim Persian, whose tone was so silky, whose eyes were so deadly, and whose small, shapely head was that of a human panther—Nadir Tous, once an emir high in the favor of the Shah of Kharesmia. And that Seljuk Turk, with his silvered mail shirt, peaked helmet and jewel-hilted scimitar—Kai Shah; he had ridden at Saladin’s side in high honor once, and it was said that the scar which showed white in the angle of his jaw had been made by the sword of Richard the Lion-hearted in that great battle before the walls of Joppa. And that wiry, tall, eagle-faced Arab, Yussef el Mekru—he had been a great sheikh once in Yemen and had even led a revolt against the Sultan himself.

But at the head of the table at which Cormac sat was one whose history for strangeness and vivid fantasy dimmed them all. Tisolino di Strozza, trader, captain of Venice’s warships, Crusader, pirate, outlaw—what a red trail the man had followed to his present casteless condition! Di Strozza was tall and thin and saturnine in appearance, with a hook-nosed, thin-nostriled face of distinctly predatory aspect. His armor, now worn and tarnished, was of costly Venetian make, and the hilt of his long narrow sword had once been set with gems. He was a man of restless soul, thought Cormac, as he watched the Venetian’s dark eyes dart continually from point to point, and the lean hand repeatedly lifted to twist the ends of the thin mustache.

Cormac’s gaze wandered to the other chiefs—wild reavers, born to the red trade of pillage and murder, whose pasts were black enough, but lacked the varied flavor of the other four. He knew these by sight or reputation—Kojar Mirza, a brawny Kurd; Shalmar Khor, a tall swaggering Circassian; and Jusus Zehor, a renegade Georgian who wore half a dozen knifes in his girdle.

There was one not known to him, a warrior who apparently had no standing among the bandits, yet who carried himself with the assurance born of prowess. He was of a type rare in the Taurus—a stocky, strongly built man whose head would come no higher than Cormac’s shoulder. Even as he ate, he wore a helmet with a lacquered leather drop, and Cormac caught the glint of mail beneath his sheepskins; through his girdle was thrust a short wide-bladed sword, not curved as much as the Moslem scimitars. His powerful bowed legs, as well as the slanting black eyes set in an inscrutable brown face, betrayed the Mongol.

He, like Cormac, was a newcomer; riding from the east he had arrived at Bab-el-Shaitan that night at the same time that the Irish warrior had ridden in from the south. His name, as given in guttural Turki, was Toghrul Khan.

A slave whose scarred face and fear-dulled eyes told of the brutality of his masters, tremblingly filled Cormac’s goblet. He started and flinched as a sudden scream faintly knifed the din; it came from somewhere above, and none of the feasters paid any attention. The Norman-Gael wondered at the absence of women-slaves. Skol Abdhur’s name was a terror in that part of Asia and many caravans felt the weight of his fury. Many women had been stolen from raided villages and camel-trains, yet now there were apparently only men in Bab-el-Shaitan. This, to Cormac, held a sinister implication. He recalled dark tales, whispered under the breath, relating to the cryptic inhumanness of the robber chief—mysterious hints of foul rites in black caverns, of naked white victims writhing on hideously ancient altars, of blood-chilling sacrifices beneath the midnight moon. But that cry had been no woman’s scream.

Kai Shah was close to di Strozza’s shoulder, talking very rapidly in a guarded tone. Cormac saw that Nadir Tous was only pretending to be absorbed in his wine cup; the Persian’s eyes, burning with intensity, were fixed on the two who whispered at the head of the table. Cormac, alert to intrigue and counter-plot, had already decided that there were factions in Bab-el-Shaitan. He had noticed that di Strozza, Kai Shah, a lean Syrian scribe named Musa bin Daoud, and the wolfish Lur, Kadra Muhammad, stayed close to each other, while Nadir Tous had his own following among the lesser bandits, wild ruffians, mostly Persians and Armenians, and Kojar Mirza was surrounded by a number of even wilder mountain Kurds. The manner of the Venetian and Nadir Tous toward each other was of a wary courtesy that seemed to mask suspicion, while the Kurdish chief wore an aspect of truculent defiance toward both.

As these thoughts passed through Cormac’s mind, an incongruous figure appeared on the landing of the broad stairs. It was Jacob, Skol Abdhur’s majordomo—a short, very fat Jew attired in gaudy and costly robes which had once decked a Syrian harem master. All eyes turned toward him, for it was evident he had brought word from his master—not often did Skol Abdhur, wary as a hunted wolf, join his pack at their feasts.

“The great prince, Skol Abdhur,” announced Jacob in pompous and sonorous accents, “would grant audience to the Nazarene who rode in at dusk—the lord Cormac FitzGeoffrey.”

The Norman finished his goblet at draft and rose deliberately, taking up his shield and helmet.

“And what of me, Yahouda?” It was the guttural voice of the Mongol. “Has the great prince no word for Toghrul Khan, who has ridden far and hard to join his horde? Has he said naught of an audience with me?”

The Jew scowled. “Lord Skol said naught of any Tartar,” he answered shortly. “Wait until he sends for you, as he will do—if it so pleases him.”

The answer was as much an insult to the haughty pagan as would have been a slap in the face. He half-made to rise then sank back, his face, schooled to iron control, showing little of his rage. But his serpent-like eyes glittering devilishly, took in not only the Jew but Cormac as well, and the Norman knew that he himself was included in Toghrul Khan’s black anger. Mongol pride and Mongol wrath are beyond the ken of the Western mind, but Cormac knew that in his humiliation, the nomad hated him as much as he hated Jacob.

But Cormac could count his friends on his fingers and his personal enemies by the scores. A few more foes made little difference and he paid no heed to Toghrul Khan as he followed the Jew up the broad stairs, and along a winding corridor to a heavy, metal-braced door before which stood, like an image carven of black basalt, a huge naked Nubian who held a two-handed scimitar whose five-foot blade was a foot wide at the tip.

Jacob made a sign to the Nubian, but Cormac saw that the Jew was trembling and apprehensive.

“In God’s name,” Jacob whispered to the Norman, “speak him softly; Skol is in a devilish temper tonight. Only a little while ago he tore out the eyeball of a slave with his hands.”

“That was that scream I heard then,” grunted Cormac. “Well, don’t stand there chattering; tell that black beast to open the door before I knock it down.”

Jacob blenched; but it was no idle threat. It was not the Norman-Gael’s nature to wait meekly at the door of any man—he who had been cup-companion to King Richard. The majordomo spoke swiftly to the mute, who swung the door open. Cormac pushed past his guide and strode across the threshold.

And for the first time he looked on Skol Abdhur the Butcher, whose deeds of blood had already made him a semi-mythical figure. The Norman saw a bizarre giant reclining on a silken divan, in the midst of a room hung and furnished like a king’s. Erect, Skol would have towered half a head taller than Cormac, and though a huge belly marred the symmetry of his figure, he was still an image of physical prowess. His short, naturally black beard had been stained to a bluish tint; his wide black eyes blazed with a curious wayward look not altogether sane at times.

He was clad in cloth-of-gold slippers whose toes turned up extravagantly, in voluminous Persian trousers of rare silk, and a wide green silken sash, heavy with golden scales, was wrapt about his waist. Above this he wore a sleeveless jacket, richly brocaded, open in front, but beneath this his huge torso was naked. His blue-black hair, held by a gemmed circlet of gold, fell to his shoulders, and his fingers were gleaming with jewels, while his bare arms were weighted with heavy gem-crusted armlets. Women’s earrings adorned his ears.

Altogether his appearance was of such fantastic barbarism as to inspire in Cormac an amazement which in an ordinary man would have been a feeling of utmost horror. The apparent savagery of the giant, together with his fantastic finery which heightened rather than lessened the terror of his appearance, lent Skol Abdhur an aspect which set him outside the pale of ordinary humanity. The effect of an ordinary man, so garbed, would have been merely ludicrous; in the robber chieftain it was one of horror.

Yet as Jacob salaamed to the floor in a very frenzy of obeisance, he was not sure that Skol looked any more formidable than the mail-clad Frank with his aspect of dynamic and terrible strength directed by a tigerish nature.

“The lord Cormac FitzGeoffrey, oh mighty prince,” proclaimed Jacob, while Cormac stood like an iron image not deigning even to incline his lion-like head.

“Yes, fool, I can see that,” Skol’s voice was deep and resonant. “Take yourself hence before I crop your ears. And see that those fools downstairs have plenty of wine.”

From the stumbling haste with which Jacob obeyed, Cormac knew the threat of cropping ears was no empty one. Now his eyes wandered to a shocking and pitiful figure—the slave standing behind Skol’s divan ready to pour wine for his grim master. The wretch was trembling in every limb as a wounded horse quivers, and the reason was apparent—a ghastly gaping socket from which the eye had been ruthlessly ripped. Blood still oozed from the rim to join the stains which blotched the twisted face and spotted the silken garments. Pitiful finery! Skol dressed his miserable slaves in apparel rich merchants might envy. And the wretch stood shivering in agony, yet not daring to move from his tracks, though with the pain-misted half-sight remaining him, he could scarcely see to fill the gem-crusted goblet Skol lifted.

“Come and sit on the divan with me, Cormac,” hailed Skol. “I would speak to you. Dog! Fill the lord Frank’s goblet, and haste, lest I take your other eye.”

“I drink no more this night,” growled Cormac, thrusting aside the goblet Skol held out to him. “And send that slave away. He’ll spill wine on you in his blindness.”

Skol stared at Cormac a moment and then with a sudden laugh waved the pain-sick slave toward the door. The man went hastily, whimpering in agony.

“See,” said Skol, “I humor your whim. But it was not necessary. I would have wrung his neck after we had talked, so he could not repeat our words.”

Cormac shrugged his shoulders. Little use to try to explain to Skol that it was pity for the slave and not desire for secrecy that prompted him to have the man dismissed.

“What think you of my kingdom, Bab-el-Shaitan?” asked Skol suddenly.

“It would be hard to take,” answered the Norman.

Skol laughed wildly and emptied his goblet.

“So the Seljuks have found,” he hiccupped. “I took it years ago by a trick from the Turk who held it. Before the Turks came the Arabs held it and before them—the devil knows. It is old—the foundations were built in the long ago by Iskander Akbar—Alexander the Great. Then centuries later came the Roumi—the Romans—who added to it. Parthians, Persians, Kurds, Arabs, Turks—all have shed blood on its walls. Now it is mine, and while I live, mine it shall remain! I know its secrets—and its secrets,” he cast the Frank a sly and wicked glance full of sinister meaning, “are more than most men reckon—even those fools Nadir Tous and di Strozza, who would cut my throat if they dared.”

“How do you hold supremacy over these wolves?” asked Cormac bluntly.

Skol laughed and drank once more.

“I have something each wishes. They hate each other; I play them against one another. I hold the key to the plot. They do not trust each other enough to move against me. I am Skol Abdhur! Men are puppets to dance on my strings. And women”—a vagrant and curious glint stole into his eyes—“women are food for the gods,” he said strangely.

“Many men serve me,” said Skol Abdhur, “emirs and generals and chiefs, as you saw. How came they here to Bab-el-Shaitan where the world ends? Ambition—intrigues—women—jealousy—hatred—now they serve the Butcher. And what brought you here, my brother? That you are an outlaw I know—that your life is forfeit to your people because you slew a certain emir of the Franks, one Count Conrad von Gonler. But only when hope is dead do men ride to Bab-el-Shaitan. There are cycles within cycles, outlaws beyond the pale of outlawry, and Bab-el-Shaitan is the end of the world.”

“Well,” growled Cormac, “one man can not raid the caravans. My friend Sir Rupert de Vaile, Seneschal of Antioch, is captive to the Turkish chief Ali Bahadur, and the Turk refuses to ransom him for the gold that has been offered. You ride far, and fall on the caravans that bring the treasures of Hind and Cathay. With you I may find some treasure so rare that the Turk will accept it as a ransom. If not, with my share of the loot I will hire enough bold rogues to rescue Sir Rupert.”

Skol shrugged his shoulders. “Franks are mad,” said he, “but whatever the reason, I am glad you rode hither. I have heard you are faithful to the lord you follow, and I need such a man. Just now I trust no one but Abdullah, the black mute that guards my chamber.”

It was evident to Cormac that Skol was fast becoming drunk. Suddenly he laughed wildly.

“You asked me how I hold my wolves in leash? Not one but would slit my throat. But look—so far I trust you I will show you why they do not!”

He reached into his girdle and drew forth a huge jewel which sparkled like a tiny lake of blood in his great palm. Even Cormac’s eyes narrowed at the sight.

“Satan!” he muttered. “That can be naught but the ruby called—”

“!” exclaimed Skol Abdhur. “Aye, the gem Cyrus the Persian ripped from the sword-gashed bosom of the great king on that red night when Babylon fell! It is the most ancient and costly gem in the world. Ten thousand pieces of heavy gold could not buy it.

“Hark, Frank,” again Skol drained a goblet, “I will tell you the tale of the Blood of Belshazzar. See you how strangely it is carved?”

He held it up and the light flashed redly from its many facets. Cormac shook his head, puzzled.

The carving was strange indeed, corresponding to nothing he had ever seen, east or west. It seemed that the ancient carver had followed some plan entirely unknown and apart from that of modern lapidary art. It was basically different with a difference Cormac could not define.

“No mortal cut that stone!” said Skol, “but the djinn of the sea! For once in the long, long ago, in the very dawn of happenings, the great king, even Belshazzar, went from his palace on pleasure bent and coming to the Green Sea—the Persian Gulf—went thereon in a royal galley, golden-prowed and rowed by a hundred slaves. Now there was one Naka, a diver of pearls, who desiring greatly to honor his king, begged the royal permission to seek the ocean bottom for rare pearls for the king, and Belshazzar granting his wish, Naka dived. Inspired by the glory of the king, he went far beyond the depth of divers, and after a time floated to the surface, grasping in his hand a ruby of rare beauty—aye, this very gem.

“Then the king and his lords, gazing on its strange carvings, were amazed, and Naka, nigh to death because of the great depth to which he had gone, gasped out a strange tale of a silent, seaweed-festooned city of marble and lapis lazuli far below the surface of the sea, and of a monstrous mummied king on a jade throne from whose dead taloned hand Naka had wrested the ruby. And then the blood burst from the diver’s mouth and ears and he died.

“Then Belshazzar’s lords entreated him to throw the gem back into the sea, for it was evident that it was the treasure of the djinn of the sea, but the king was as one mad, gazing into the crimson deeps of the ruby, and he shook his head.

“And lo, soon evil came upon him, for the Persians broke his kingdom, and Cyrus, looting the dying monarch, wrested from his bosom the great ruby which seemed so gory in the light of the burning palace that the soldiers shouted: ‘Lo, it is the heart’s blood of Belshazzar!’ And so men came to call the gem the Blood of Belshazzar.

“Blood followed its course. When Cyrus fell on the Jaxartes, Queen Tomyris seized the jewel and for a time it gleamed on the naked bosom of the Scythian queen. But she was despoiled of it by a rebel general; in a battle against the Persians he fell and it went into the hands of Cambyses, who carried it with him into Egypt, where a priest of Bast stole it. A Numidian mercenary murdered him for it, and by devious ways it came back to Persia once more. It gleamed on Xerxes’ crown when he watched his army destroyed at Salamis.

“Alexander took it from the corpse of Darius and on the Macedonian’s corselet its gleams lighted the road to India. A chance sword blow struck it from his breastplate in a battle on the Indus and for centuries the Blood of Belshazzar was lost to sight. Somewhere far to the east, we know, its gleams shone on a road of blood and rapine, and men slew men and dishonored women for it. For it, as of old, women gave up their virtue, men their lives and kings their crowns.

“But at last its road turned to the west once more, and I took it from the body of a Turkoman chief I slew in a raid far to the east. How he came by it, I do not know. But now it is mine!”

Skol was drunk; his eyes blazed with inhuman passion; more and more he seemed like some foul bird of prey.

“It is my balance of power! Men come to me from palace and hovel, each hoping to have the Blood of Belshazzar for his own. I play them against each other. If one should slay me for it, the others would instantly cut him to pieces to gain it. They distrust each other too much to combine against me. And who would share the gem with another?”

He poured himself wine with an unsteady hand.

“I am Skol the Butcher!” he boasted, “a prince in my own right! I am powerful and crafty beyond the knowledge of common men. For I am the most feared chieftain in all the Taurus, I who was dirt beneath men’s feet, the disowned and despised son of a renegade Persian noble and a Circassian slave-girl.

“Bah—these fools who plot against me—the Venetian, Kai Shah, Musa bin Daoud and Kadra Muhammad—over against them I play Nadir Tous, that polished cutthroat, and Kojar Mirza. The Persian and the Kurd hate me and they hate di Strozza, but they hate each other even more. And Shalmar Khor hates them all.”

“And what of Seosamh el Mekru?” Cormac could not twist his Norman-Celtic tongue to the Arabic of Joseph.

“Who knows what is in an Arab’s mind?” growled Skol. “But you may be certain he is a jackal for loot, like all his kind, and will watch which way the feather falls, to join the stronger side—and then betray the winners.

“But I care not!” the robber roared suddenly. “I am Skol the Butcher! Deep in the deeps of the Blood have I seen misty, monstrous shapes and read dark secrets! Aye—in my sleep I hear the whispers of that dead, half-human king from whom Naka the diver tore the jewel so long ago. Blood! That is a drink the ruby craves! Blood follows it; blood is drawn to it! Not the head of Cyrus did Queen Tomyris plunge into a vessel of warm blood as the legends say, but the gem she took from the dead king! He who wears it must quench its thirst or it will drink his own blood! Aye, the heart’s flow of kings and queens have gone into its crimson shadow!

“And I have quenched its thirst! There are secrets of Bab-el-Shaitan none knows but I—and Abdullah whose withered tongue can never speak of the sights he has looked upon, the shrieks his ears have heard in the blackness below the castle when midnight holds the mountains breathless. For I have broken into secret corridors, sealed up by the Arabs who rebuilt the hold, and unknown to the Turks who followed them.”

He checked himself as if he had said too much. But the crimson dreams began to weave again their pattern of insanity.

“You have wondered why you see no women here? Yet hundreds of fair girls have passed through the portals of Bab-el-Shaitan. Where are they now? Ha ha ha!” the giant’s sudden roar of ghastly laughter thundered in the room.

“Many went to quench the ruby’s thirst,” said Skol, reaching for the wine jug, “or to become the brides of the Dead, the concubines of ancient demons of the mountains and deserts, who take fair girls only in death throes. Some I or my warriors merely wearied of, and they were flung to the vultures.”

Cormac sat, chin on mailed fist, his dark brows lowering in disgust.

“Ha!” laughed the robber. “You do not laugh—are you thin-skinned, lord Frank? I have heard you spoken of as a desperate man. Wait until you have ridden with me for a few moons! Not for nothing am I named the Butcher! I have built a pyramid of skulls in my day! I have severed the necks of old men and old women, I have dashed out the brains of babes, I have ripped up women, I have burned children alive and sat them by scores on pointed stakes! Pour me wine, Frank.”

“Pour your own damned wine,” growled Cormac, his lip writhing back dangerously.

“That would cost another man his head,” said Skol, reaching for his goblet. “You are rude of speech to your host and the man you have ridden so far to serve. Take care—rouse me not.” Again he laughed his horrible laughter.

“These walls have re-echoed to screams of direst agony!” his eyes began to burn with a reckless and maddened light. “With these hands have I disemboweled men, torn out the tongues of children and ripped out the eyeballs of girls—thus!”

With a shriek of crazed laughter his huge hand shot at Cormac’s face. With an oath the Norman caught the giant’s wrist and bones creaked in that iron grip. Twisting the arm viciously down and aside with a force that nearly tore it from its socket, Cormac flung Skol back on the divan.

“Save your whims for your slaves, you drunken fool,” the Norman rasped.

Skol sprawled on the divan, grinning like an idiotic ogre and trying to work his fingers which Cormac’s savage grasp had numbed. The Norman rose and strode from the chamber in fierce disgust; his last backward glance showed Skol fumbling with the wine jug, with one hand still grasping the Blood of Belshazzar, which cast a sinister light all over the room.

The door shut behind Cormac and the Nubian cast him a sidelong, suspicious glance. The Norman shouted impatiently for Jacob, and the Jew bobbed up suddenly and apprehensively. His face cleared when Cormac brusquely demanded to be shown his chamber. As he tramped along the bare, torch-lighted corridors, Cormac heard sounds of revelry still going on below. Knives would be going before morning, reflected Cormac, and some would not see the rising of the sun. Yet the noises were neither as loud nor as varied as they had been when he left the banquet hall; no doubt many were already senseless from strong drink.

Jacob turned aside and opened a heavy door, his torch revealing a small cell-like room, bare of hangings, with a sort of bunk on one side; there was a single window, heavily barred, and but one door. The Jew thrust the torch into a niche of the wall.

“Was the lord Skol pleased with you, my lord?” he asked nervously.

Cormac cursed. “I rode over a hundred miles to join the most powerful raider in the Taurus, and I find only a wine-bibbing, drunken fool, fit only to howl bloody boasts and blasphemies to the roof.”

“Be careful, for God’s sake, sir,” Jacob shook from head to foot. “These walls have ears! The great prince has these strange moods, but he is a mighty fighter and a crafty man for all that. Do not judge him in his drunkenness. Did—did—did he speak aught of me?”

“Aye,” answered Cormac at random, a whimsical grim humor striking him. “He said you only served him in hopes of stealing his ruby some day.”

Jacob gasped as if Cormac had hit him in the belly and the sudden pallor of his face told the Norman his chance shot had gone home. The majordomo ducked out of the room like a scared rabbit and it was in somewhat better humor that his tormentor turned to retire.

Looking out the window, Cormac glanced down into the courtyard where the animals were kept, at the stables wherein he had seen that his great black stallion had been placed. Satisfied that the steed was well sheltered for the night, he lay down on the bunk in full armor, with his shield, helmet and sword beside him, as he was wont to sleep in strange holds. He had barred the door from within, but he put little trust in bolts and bars.

Cormac had been asleep less than an hour when a sudden sound brought him wide awake and alert. It was utterly dark in the chamber; even his keen eyes could make out nothing, but someone or something was moving on him in the darkness. He thought of the evil reputation of Bab-el-Shaitan and a momentary shiver shook him—not of fear but of superstitious revulsion.

Then his practical mind asserted itself. It was that fool Toghrul Khan who had slipped into his chamber to cleanse his strange nomadic honor by murdering the man who had been given priority over him. Cormac cautiously drew his legs about and lifted his body until he was sitting on the side of the bunk. At the rattle of his mail, the stealthy sounds ceased, but the Norman could visualize Toghrul Khan’s slant eyes glittering snake-like in the dark. Doubtless he had already slit the throat of Jacob the Jew.

As quietly as possible, Cormac eased the heavy sword from its scabbard. Then as the sinister sounds recommenced, he tensed himself, made a swift estimate of location, and leaped like a huge tiger, smiting blindly and terribly in the dark. He had judged correctly. He felt the sword strike solidly, crunching through flesh and bone, and a body fell heavily in the darkness.

Feeling for flint and steel, he struck fire to tinder and lighted the torch, then turning to the crumpled shape in the center of the room, he halted in amazement. The man who lay there in a widening pool of crimson was tall, powerfully built and hairy as an ape—Kadra Muhammad. The Lur’s scimitar was in his scabbard, but a wicked dagger lay by his right hand.

“He had no quarrel with me,” growled Cormac, puzzled. “What—” He stopped again. The door was still bolted from within, but in what had been a blank wall to the casual gaze, a black opening gaped—a secret doorway through which Kadra Muhammad had come. Cormac closed it and with sudden purpose pulled his coif in place and donned his helmet. Then taking up his shield, he opened the door and strode forth into the torch-lighted corridor. All was silence, broken only by the tramp of his iron-clad feet on the bare flags. The sounds of revelry had ceased and a ghostly stillness hung over Bab-el-Shaitan.

In a few minutes he stood before the door of Skol Abdhur’s chamber and saw there what he had half-expected. The Nubian Abdullah lay before the threshold, disemboweled, and his woolly head half severed from his body. Cormac thrust open the door; the candles still burned. On the floor, in the blood-soaked ruins of the torn divan lay the gashed and naked body of Skol Abdhur the Butcher. The corpse was slashed and hacked horribly, but it was evident to Cormac that Skol had died in drunken sleep with no chance to fight for his life. It was some obscure hysteria or frantic hatred that had led his slayer or slayers to so disfigure his dead body. His garments lay near him, ripped to shreds. Cormac smiled grimly, nodding.

“So the Blood of Belshazzar drank your life at last, Skol,” said he.

Turning toward the doorway he again scanned the body of the Nubian.

“More than one slew these men,” he muttered, “and the Nubian gave scathe to one, at least.”

The black still gripped his great scimitar, and the edge was nicked and bloodstained.

At that moment a quick rattle of steps sounded on the flags and the affrighted face of Jacob peered in at the door. His eyes flared wide and he opened his mouth to the widest extent to give vent to an ear-piercing screech.

“Shut up, you fool,” snarled Cormac disgusted, but Jacob gibbered wildly.

“Spare my life, most noble lord! I will not tell anyone that you slew Skol—I swear—”

“Be quiet, Jew,” growled Cormac. “I did not slay Skol and I will not harm you.”

This somewhat reassured Jacob, whose eyes narrowed with sudden avarice.

“Have you found the gem?” he chattered, running into the chamber. “Swift, let us search for it and begone—I should not have shrieked but I feared the noble lord would slay me—yet perchance it was not heard—”

“It was heard,” growled the Norman. “And here are the warriors.”

The tramp of many hurried feet was heard and a second later the door was thronged with bearded faces. Cormac noted the men blinked and gaped like owls, more like men roused from deep sleep than drunken men. Bleary-eyed, they gripped their weapons and ogled, a ragged, bemused horde. Jacob shrank back, trying to flatten himself against the wall, while Cormac faced them, bloodstained sword still in his hand.

“Allah!” ejaculated a Kurd, rubbing his eyes. “The Frank and the Jew have murdered Skol!”

“A lie,” growled Cormac menacingly. “I know not who slew this drunkard.”

Tisolino di Strozza came into the chamber, followed by the other chiefs. Cormac saw Nadir Tous, Kojar Mirza, Shalmar Khor, Yussef el Mekru and Justus Zenor. Toghrul Khan, Kai Shah and Musa bin Daoud were nowhere in evidence, and where Kadra Muhammad was, the Norman well knew.

“The jewel!” exclaimed an Armenian excitedly. “Let us look for the gem!”

“Be quiet, fool,” snapped Nadir Tous, a light of baffled fury growing in his eyes. “Skol has been stripped; be sure who slew him took the gem.”

All eyes turned toward Cormac.

“Skol was a hard master,” said Tisolino. “Give us the jewel, lord Cormac, and you may go your way in peace.”

Cormac swore angrily; had not, he thought, even as he replied, the Venetian’s eyes widened when they first fell on him?

“I have not your cursed jewel; Skol was dead when I came to his room.”

“Aye,” jeered Kojar Mirza, “and blood still wet on your blade.” He pointed accusingly at the weapon in Cormac’s hand, whose blue steel, traced with Norse runes, was stained a dull red.

“That is the blood of Kadra Muhammad,” growled Cormac, “who stole into my cell to slay me and whose corpse now lies there.”

His eyes were fixed with fierce intensity on di Strozza’s face but the Venetian’s expression altered not a whit.

“I will go to the chamber and see if he speaks truth,” said di Strozza, and Nadir Tous smiled a deadly smile.

“You will remain here,” said the Persian, and his ruffians closed menacingly around the tall Venetian. “Go you, Selim.” And one of his men went grumbling. Di Strozza shot a swift glance of terrible hatred and suppressed wrath at Nadir Tous, then stood imperturbably; but Cormac knew that the Venetian was wild to escape from that room.

“There have been strange things done tonight in Bab-el-Shaitan,” growled Shalmar Khor. “Where are Kai Shah and the Syrian—and that pagan from Tartary? And who drugged the wine?”

“Aye!” exclaimed Nadir Tous, “who drugged the wine which sent us all into the sleep from which we but a few moments ago awakened? And how is it that you, di Strozza, were awake when the rest of us slept?”

“I have told you, I drank the wine and fell asleep like the rest of you,” answered the Venetian coldly. “I awoke a few moments earlier, that is all, and was going to my chamber when the horde of you came along.”

“Mayhap,” answered Nadir Tous, “but we had to put a scimitar edge to your throat before you would come with us.”

“Why did you wish to come to Skol’s chamber anyway?” countered di Strozza.

“Why,” answered the Persian, “when we awoke and realized we had been drugged, Shalmar Khor suggested that we go to Skol’s chamber and see if he had flown with the jewel—”

“You lie!” exclaimed the Circassian. “That was Kojar Mirza who said that—”

“Why this delay and argument!” cried Kojar Mirza. “We know this Frank was the last to be admitted to Skol this night. There is blood on his blade—we found him standing above the slain! Cut him down!”

And drawing his scimitar he stepped forward, his warriors surging in behind him. Cormac placed his back to the wall and braced his feet to meet the charge. But it did not come; the tense figure of the giant Norman-Gael was so fraught with brooding menace, the eyes glaring so terribly above the skull-adorned shield, that even the wild Kurd faltered and hesitated, though a score of men thronged the room and many more than that number swarmed in the corridor outside. And as he wavered the Persian Selim elbowed his way through the band, shouting: “The Frank spoke truth! Kadra Muhammad lies dead in the lord Cormac’s chamber!”

“That proves nothing,” said the Venetian quietly. “He might have slain Skol after he slew the Lur.”

An uneasy and bristling silence reigned for an instant. Cormac noted that now Skol lay dead, the different factions made no attempt to conceal their differences. Nadir Tous, Kojar Mirza and Shalmar Khor stood apart from each other and their followers bunched behind them in glaring, weapon-thumbing groups. Yussef el Mekru and Justus Zehor stood aside, looking undecided; only di Strozza seemed oblivious to this cleavage of the robber band.

The Venetian was about to say more, when another figure shouldered men aside and strode in. It was the Seljuk, Kai Shah, and Cormac noted that he lacked his mail shirt and that his garments were different from those he had worn earlier in the night. More, his left arm was bandaged and bound close to his chest and his dark face was somewhat pale.

At the sight of him di Strozza’s calm for the first time deserted him; he started violently.

“Where is Musa bin Daoud?” he exclaimed.

“Aye!” answered the Turk angrily. “Where is Musa bin Daoud?”

“I left him with you!” cried di Strozza fiercely, while the others gaped, not understanding this byplay.

“But you planned with him to elude me,” accused the Seljuk.

“You are mad!” shouted di Strozza, losing his self-control entirely.

“Mad?” snarled the Turk. “I have been searching for the dog through the dark corridors. If you and he are acting in good faith, why did you not return to the chamber, when you went forth to meet Kadra Muhammad whom we heard coming along the corridor? When you came not back I stepped to the door to peer out for you, and when I turned back, Musa had darted through some secret opening like a rat—”

Di Strozza almost frothed at the mouth. “You fool!” he screamed, “keep silent!”

“I will see you in Gehennum and all our throats cut before I let you cozen me!” roared the Turk, ripping out his scimitar. “What have you done with Musa?”

“You fool of Hell,” raved di Strozza, “I have been in this chamber ever since I left you! You knew that Syrian dog would play us false if he got the opportunity and—”

And at that instant when the air was already supercharged with tension, a terrified slave rushed in at a blind, stumbling run, to fall gibbering at di Strozza’s feet.

“The gods!” he howled. “The black gods! Aie! The cavern under the floors and the djinn in the rock!”

“What are you yammering about, dog?” roared the Venetian, knocking the slave to the floor with an open-handed blow.

“I found the forbidden door open,” screeched the fellow. “A stair goes down—it leads into a fearful cavern with a terrible altar on which frown gigantic demons—and at the foot of the stairs—the lord Musa—”

“What!” di Strozza’s eyes blazed and he shook the slave as a dog shakes a rat.

“Dead!” gasped the wretch between chattering teeth.

Cursing terribly, di Strozza knocked men aside in his rush to the door; with a vengeful howl Kai Shah pelted after him, slashing right and left to clear a way. Men gave back from his flashing blade, howling as the keen edge slit their skins. The Venetian and his erstwhile comrade ran down the corridor, di Strozza dragging the screaming slave after him, and the rest of the pack gave tongue in rage and bewilderment and took after them. Cormac swore in amazement and followed, determined to see the mad game through.

Down winding corridors di Strozza led the pack, down broad stairs, until he came to a huge iron door that now swung open. Here the horde hesitated.

“This is in truth the forbidden door,” muttered an Armenian. “The brand is on my back that Skol put there merely because I lingered too long before it once.”

“Aye,” agreed a Persian. “It leads into places once sealed up by the Arabs long ago. None but Skol ever passed through that door—he and the Nubian and the captives who came not forth. It is a haunt of devils.”

Di Strozza snarled in disgust and strode through the doorway. He had snatched a torch as he ran and he held this high in one hand. Broad steps showed, leading downward, and cut out of solid rock. They were on the lower floor of the castle; these steps led into the bowels of the earth. As di Strozza strode down, dragging the howling, naked slave, the high-held torch lighting the black stone steps and casting long shadows into the darkness before them, the Venetian looked like a demon dragging a soul into Hell.

Kai Shah was close behind him with his drawn scimitar, with Nadir Tous and Kojar Mirza crowding him close. The ragged crew had, with unaccustomed courtesy, drawn back to let the lord Cormac through and now they followed, uneasily and casting apprehensive glances to all sides.

Many carried torches, and as their light flowed into the depths below a medley of affrighted yells went up. From the darkness huge evil eyes glimmered and titanic shapes loomed vaguely in the gloom. The mob wavered, ready to stampede, but di Strozza strode stolidly downward and the pack called on Allah and followed. Now the light showed a huge cavern in the center of which stood a black and utterly abhorrent altar, hideously stained, and flanked with grinning skulls laid out in strangely systematic lines. The horrific figures were disclosed to be huge images, carved from the solid rock of the cavern walls, strange, bestial, gigantic gods, whose huge eyes of some glassy substance caught the torchlight.

The Celtic blood in Cormac sent a shiver down his spine. Alexander built the foundations of this fortress? Bah—no Grecian ever carved such gods as these. No; an aura of unspeakable antiquity brooded over this grim cavern, as if the forbidden door were a mystic threshold over which the adventurer stepped into an elder world. No wonder mad dreams were here bred in the frenzied brain of Skol Abdhur. These gods were grim vestiges of an older, darker race than Roman or Hellene—a people long faded into the gloom of antiquity. Phrygians—Lydians—Hittites? Or some still more ancient, more abysmal people?

The age of Alexander was as dawn before these ancient figures, yet doubtless he bowed to these gods, as he bowed to many gods before his maddened brain made himself a deity.

At the foot of the stairs lay a crumpled shape—Musa bin Daoud. His face was twisted in horror. A medley of shouts went up: “The djinn have taken the Syrian! Let us begone! This is an evil place!”

“Be silent, you fools!” roared Nadir Tous. “A mortal blade slew Musa—see, he has been slashed through the breast and his bones are broken. See how he lies. Someone slew him and flung him down the stairs—”

The Persian’s voice trailed off, as his gaze followed his own pointing fingers. Musa’s left arm was outstretched and his fingers had been hacked away.

“He held something in that hand,” whispered Nadir Tous. “So hard he gripped it that his slayer was forced to cut off his fingers to obtain it—”

Men thrust torches into niches on the wall and crowded nearer, their superstitious fears forgotten.

“Aye!” exclaimed Cormac, having pieced together some of the bits of the puzzle in his mind. “It was the gem! Musa and Kai Shah and di Strozza killed Skol, and Musa had the gem. There was blood on Abdullah’s sword and Kai Shah has a broken arm—shattered by the sweep of the Nubian’s great scimitar. Whoever slew Musa has the gem.”

Di Strozza screamed like a wounded panther. He shook the wretched slave.

“Dog, have you the gem?”

The slave began a frenzied denial, but his voice broke in a ghastly gurgle as di Strozza, in a very fit of madness, jerked his sword edge across the wretch’s throat and flung the blood-spurting body from him. The Venetian whirled on Kai Shah.

“You slew Musa!” he screamed. “He was with you last! You have the gem!”

“You lie!” exclaimed the Turk, his dark face an ashy pallor. “You slew him yourself—”

His words ended in a gasp as di Strozza, foaming at the mouth and all sanity gone from his eyes, ran his sword straight through the Turk’s body. Kai Shah swayed like a sapling in the wind; then as di Strozza withdrew the blade, the Seljuk hacked through the Venetian’s temple, and as Kai Shah reeled, dying on his feet but clinging to life with the tenacity of the Turk, Nadir Tous leaped like a panther and beneath his flashing scimitar Kai Shah dropped dead across the dead Venetian.

Forgetting all else in his lust for the gem, Nadir Tous bent over his victim, tearing at his garments—bent further as if in a deep salaam and sank down on the dead men, his own skull split to the teeth by Kojar Mirza’s stroke. The Kurd bent to search the Turk, but straightened swiftly to meet the attack of Shalmar Khor. In an instant the scene was one of ravening madness, where men hacked and slew and died blindly. The flickering torches lit the scene, and Cormac, backing away toward the stairs, swore amazedly. He had seen men go mad before, but this exceeded anything he had ever witnessed.

Kojar Mirza slew Selim and wounded a Circassian, but Shalmar Khor slashed through his arm-muscles, Justus Zehor ran in and stabbed the Kurd in the ribs, and Kojar Mirza went down, snapping like a dying wolf, to be hacked to pieces.

Justus Zehor and Yussef el Mekru seemed to have taken sides at last; the Georgian had thrown in his lot with Shalmar Khor, while the Arab rallied to him the Kurds and Turks. But besides these loosely knit bands of rivals, various warriors, mainly the Persians of Nadir Tous, raged through the strife, foaming at the mouth and striking all impartially. In an instant a dozen men were down, dying and trampled by the living. Justus Zehor fought with a long knife in each hand and he wrought red havoc before he sank, skull cleft, throat slashed and belly ripped up.

Even while they fought, the warriors had managed to tear to shreds the clothing of Kai Shah and di Strozza. Finding naught there, they howled like wolves and fell to their deadly work with new frenzy. A madness was on them; each time a man fell, others seized him, ripping his garments apart in search for the gem, slashing at each other as they did so.

Cormac saw Jacob trying to steal to the stairs, and even as the Norman decided to withdraw himself, a thought came to the brain of Yussef el Mekru. Arab-like, the Yemenite had fought more coolly than the others, and perhaps he had, even in the frenzy of combat, decided on his own interests. Possibly, seeing that all the leaders were down except Shalmar Khor, he decided it would be best to reunite the band, if possible, and it could be best done by directing their attention against a common foe. Perhaps he honestly thought that since the gem had not been found, Cormac had it. At any rate, the Sheikh suddenly tore away and pointing a lean arm toward the giant figure at the foot of the stairs, screamed: “Allahu akbar! There stands the thief! Slay the Nazarene!”

It was good Moslem psychology. There was an instant of bewildered pause in the battle, then a bloodthirsty howl went up and from a tangled battle of rival factions, the brawl became instantly a charge of a solid compact body that rushed wild-eyed on Cormac howling: “Slay the Caphar!”

Cormac snarled in disgusted irritation. He should have anticipated that. No time to escape now; he braced himself and met the charge. A Kurd, rushing in headlong, was impaled on the Norman’s long blade, and a giant Circassian, hurling his full weight on the kite-shaped shield, rebounded as from an iron tower. Cormac thundered his battle cry, “Cloigeand abu,” (Gaelic: “The skull to victory.”) in a deep-toned roar that drowned the howls of the Moslems; he freed his blade and swung the heavy weapon in a crashing arc. Swords shivered to singing sparks and the warriors gave back. They plunged on again as Yussef el Mekru lashed them with burning words. A big Armenian broke his sword on Cormac’s helmet and went down with his skull split. A Turk slashed at the Norman’s face and howled as his wrist was caught on the Norse sword, and the hand flew from it.

Cormac’s defense was his armor, the unshakable immovability of his stance, and his crashing blows. Head bent, eyes glaring above the rim of his shield, he made scant effort to parry or avoid blows. He took them on his helmet or his shield and struck back with thunderous power. Now Shalmar Khor smote full on his helmet with every ounce of his great rangy body behind the blow, and the scimitar bit through the steel cap, notching on the coif links beneath. It was a blow that might have felled an ox, yet Cormac, though half-stunned, stood like a man of iron and struck back with all the power of arm and shoulders. The Circassian flung up his round buckler but it availed not. Cormac’s heavy sword sheared through the buckler, severed the arm that held it and crashed full on the Circassian’s helmet, shattering both steel cap and the skull beneath.

But fired by fanatical fury as well as greed, the Moslems pressed in. They got behind him. Cormac staggered as a heavy weight landed full on his shoulders. A Kurd had stolen up the stairs and leaped from them full on to the Frank’s back. Now he clung like an ape, slavering curses and hacking wildly at Cormac’s neck with his long knife.

The Norman’s sword was wedged deep in a split breastbone and he struggled fiercely to free it. His hood was saving him so far from the knife strokes of the man on his back, but men were hacking at him from all sides and Yussef el Mekru, foam on his beard, was rushing upon him. Cormac drove his shield upward, catching a frothing Moslem under the chin with the rim and shattering his jawbone, and almost at the same instant the Norman bent his helmeted head forward and jerked it back with all the strength of his mighty neck, and the back of his helmet crushed the face of the Kurd on his back. Cormac felt the clutching arms relax; his sword was free, but a Lur was clinging to his right arm—they hemmed him in so he could not step back, and Yussef el Mekru was hacking at his face and throat. He set his teeth and lifted his sword-arm, swinging the clinging Lur clear of the floor. Yussef’s scimitar rasped on his bent helmet—his hauberk—his coif links—the Arab’s swordplay was like the flickering of light and in a moment it was inevitable that the flaming blade would sink home. And still the Lur clung, ape-like, to Cormac’s mighty arm.

Something whispered across the Norman’s shoulder and thudded solidly. Yussef el Mekru gasped and swayed, clawing at the thick shaft that protruded from his heavy beard. Blood burst from his parted lips and he fell dying. The man clinging to Cormac’s arm jerked convulsively and fell away. The press slackened. Cormac, panting, stepped back and gained the stairs. A glance upward showed him Toghrul Khan standing on the landing bending a heavy bow. The Norman hesitated; at that range the Mongol could drive a shaft through his mail.

“Haste, bogatyr,” came the nomad’s gutturals. “Up the stairs!”

At that instant Jacob started running fleetly for the darkness beyond the flickering torches; three steps he took before the bow twanged. The Jew screamed and went down as though struck by a giant’s hand; the shaft had struck between his fat shoulders and gone clear through him.

Cormac was backing warily up the stairs, facing his foes who clustered at the foot of the steps, dazed and uncertain. Toghrul Khan crouched on the landing, beady eyes a-glitter, shaft on string, and men hesitated. But one dared—a tall Turkoman with the eyes of a mad dog. Whether greed for the gem he thought Cormac carried, or fanatical hate sent him leaping into the teeth of sword and arrow, he sprang howling up the stairs, lifting high a heavy iron-braced shield. Toghrul Khan loosed, but the shaft glanced from the metal work, and Cormac, bracing his legs again, struck downward with all his power. Sparks flashed as the down-crashing sword shattered the shield and dashed the onrushing Turkoman headlong to lie stunned and bloodied at the foot of the stairs.

Then as the warriors fingered their weapons undecidedly, Cormac gained the landing, and Norman and Mongol backed together out of the door which Toghrul Khan slammed behind them. A wild medley of wolfish yells burst out from below and the Mongol, slamming a heavy bolt in place, growled: “Swiftly, bogatyr! It will be some minutes before those dog-brothers can batter down the door. Let us begone!”

He led the way at a swift run along a corridor, through a series of chambers, and flung open a barred door. Cormac saw that they had come into the courtyard, flooded now by the gray light of dawn. A man stood near, holding two horses—the great black stallion of Cormac’s and the Mongol’s wiry roan. Leaning close Cormac saw that the man’s face was bandaged so that only one eye showed.

“Haste,” Toghrul Khan was urging. “The slave saddled my mount, but yours he could not saddle because of the savagery of the beast. The serf is to go with us.”

Cormac made haste to comply; then swinging into the saddle he gave the fellow a hand and the slave sprang up behind him. The strangely assorted companions thundered across the courtyard just as raging figures burst through the doorway through which they had come.

“No sentries at the gates this night,” grunted the Mongol.

They pulled up at the wide gates and the slave sprang down to open them. He swung the portals wide, took a single step toward the black stallion and went down, dead before he struck the ground. A crossbow bolt had shattered his skull, and Cormac, wheeling with a curse, saw a Moslem kneeling on one of the bastions, aiming his weapon. Even as he looked, Toghrul Khan rose in his stirrups, drew a shaft to the head and loosed. The Moslem dropped his arbalest and pitched headlong from the battlement.

With a fierce yell the Mongol wheeled away and charged through the gates, Cormac close at his heels. Behind them sounded a wild and wolfish babble as the warriors rushed about the courtyard, seeking to find and saddle mounts.

“Look!” The companions had covered some miles of wild gorges and treacherous slopes, without hearing any sound of pursuit. Toghrul Khan pointed back. The sun had risen in the east, but behind them a red glow rivaled the sun.

“The Gate of Erlik burns,” said the Mongol. “They will not hunt us, those dog-brothers. They stopped to loot the castle and fight one another; some fool has set the hold on fire.”

“There is much I do not understand,” said Cormac slowly. “Let us sift truth from lies. That di Strozza, Kai Shah and Musa killed Skol is evident, also that they sent Kadra Muhammad to slay me—why, I know not. But I do not understand what Kai Shah meant by saying that they heard Kadra Muhammad coming down the corridor, and that di Strozza went forth to meet him, for surely at that moment Kadra Muhammad lay dead on my chamber floor. And I believe that both Kai Shah and the Venetian spoke truth when they denied slaying Musa.”

“Aye,” acknowledged the Mongol. “Harken, lord Frank: scarcely had you gone up to Skol’s chamber last night, when Musa the scribe left the banquet hall and soon returned with slaves who bore a great bowl of spiced wine—prepared in the Syrian way, said the scribe, and the steaming scent of it was pleasant.

“But I noted that neither he nor Kadra Muhammad drank of it, and when Kai Shah and di Strozza plunged in their goblets, they only pretended to drink. So when I raised my goblet to my lips, I sniffed long and secretly and smelled therein a very rare drug—aye, one I had thought was known only to the magicians of Cathay. It makes deep sleep and Musa must have obtained a small quantity in some raid on a caravan from the East. So I did not drink of the wine, but all the others drank saving those I have mentioned, and soon men began to grow drowsy, though the drug acted slowly, being weak in that it was distributed among so many.

“Soon I went to my chamber which a slave showed me, and squatting on my bunk, devised a plan of vengeance in my mind, for because that dog of a Jew put shame upon me before the lords, hot anger burned in my heart so that I could not sleep. Soon I heard one staggering past my door as a drunkard staggers, but this one whined like a dog in pain. I went forth and found a slave whose eye, he said, his master had torn out. I have some knowledge of wounds, so I cleansed and bandaged his empty socket, easing his pain, for which he would have kissed my feet.

“Then I bethought me of the insult which had been put upon me, and desired the slave to show me where slept the fat hog, Jacob. He did so, and marking the chamber in my mind, I turned again and went with the slave into the courtyard where the beasts were kept. None hindered us, for all were in the feasting-hall and their din was growing lesser swiftly. In the stables I found four swift horses, ready saddled—the mounts of di Strozza and his comrades. And the slave told me, furthermore, that there were no guards at the gates that night—di Strozza had bidden all to feast in the great hall. So I bade the slave saddle my steed and have it ready, and also your black stallion which I coveted.

“Then I returned into the castle and heard no sound; all those who had drunk of the wine slept in the sleep of the drug. I mounted to the upper corridors, even to Jacob’s chamber, but when I entered to slit his fat throat, he was not sleeping there. I think he was guzzling wine with the slaves in some lower part of the castle.

“I went along the corridors searching for him, and suddenly saw ahead of me a chamber door partly open, through which shone light, and I heard the voice of the Venetian speak: ‘Kadra Muhammad is approaching; I will bid him hasten.’

“I did not desire to meet these men, so I turned quickly down a side corridor, hearing di Strozza call the name of Kadra Muhammad softly and as if puzzled. Then he came swiftly down the corridor, as if to see whose footfalls it was he heard, and I went hurriedly before him, crossing the landing of a wide stair which led up from the feasting-hall, and entered another corridor where I halted in the shadows and watched.

“Di Strozza came to the landing and paused, like a man bewildered, and at that moment an outcry went up from below. The Venetian turned to escape but the waking drunkards had seen him. Just as I had thought, the drug was too weak to keep them sleeping long, and now they realized they had been drugged and stormed bewilderedly up the stairs and laid hold on di Strozza, accusing him of many things and making him accompany them to Skol’s chamber. Me they did not spy.

“Still seeking Jacob, I went swiftly down the corridor at random and coming onto a narrow stairway, came at last to the ground floor and a dark tunnel-like corridor which ran past a most strange door. And then sounded quick footsteps and as I drew back in the shadows, there came one in panting haste—the Syrian Musa, who gripped a scimitar in his right hand and something hidden in his left.

“He fumbled with the door until it opened; then lifting his head, he saw me and crying out wildly he slashed at me with his scimitar. Erlik! I had no quarrel with the man, but he was as one maddened by fear. I struck with the naked steel, and he, being close to the landing inside the door, pitched headlong down the stairs.

“Then I was desirous of learning what he held so tightly in his left hand, so I followed him down the stairs. Erlik! That was an evil place, dark and full of glaring eyes and strange shadows. The hair on my head stood up but I gripped my steel, calling on the Lords of Darkness and the high places. Musa’s dead hand still gripped what he held so firmly that I was forced to cut off the fingers. Then I went back up the stairs and out the same way by which we later escaped from the castle, and found the slave ready with my mount, but unable to saddle yours.

“I was loath to depart without avenging my insult, and as I lingered I heard the clash of steel within the hold. And I stole back and came to the forbidden stair again while the fighting was fiercest below. All were assailing you, and though my heart was hot against you, because you had been given preference over me, I warmed to your valor. Aye, you are a hero, bogatyr!”

“Then it was thus, apparently,” mused the Frank, “di Strozza and his comrades had it well planned out—they drugged the wine, called the guards from the walls, and had their horses ready for swift flight. As I had not drunk the drugged wine, they sent the Lur to slay me. The other three killed Skol and in the fight Kai Shah was wounded—Musa took the gem doubtless because neither Kai Shah nor the Venetian would trust it to the other.

“After the murder, they must have retired into a chamber to bandage Kai Shah’s arm, and while there they heard you coming along the corridor and thought it the Lur. Then when di Strozza followed he was seized by the waking bandits, as you say—no wonder he was wild to be gone from Skol’s chamber! And meanwhile Musa gave Kai Shah the slip somehow, meaning to have the gem for himself. But what of the gem?”

“Look!” the nomad held out his hand in which a sinister crimson glow throbbed and pulsed like a living thing in the early sun.

“,” said Toghrul Khan. “Greed for this slew Skol and fear born of this evil thing slew Musa; for, escaping from his comrades, he thought the hand of all men against him and attacked me, when he could have gone on unmolested. Did he think to remain hidden in the cavern until he could slip away, or does some tunnel admit to outer air?

“Well, this red stone is evil—one can not eat it or drink it or clothe himself with it, or use it as a weapon, yet many men have died for it. Look—I will cast it away.” The Mongol turned to fling the gem over the verge of the dizzy precipice past which they were riding. Cormac caught his arm.

“Nay—if you do not want it, let me have it.”

“Willingly,” but the Mongol frowned. “My brother would wear the gaud?”

Cormac laughed shortly and Toghrul Khan smiled.

“I understand; you will buy favor from your sultan.”

“Bah!” Cormac growled, “I buy favor with my sword. No.” He grinned, well pleased. “This trinket will pay the ransom of Sir Rupert de Vaile to the chief who now holds him captive.”