Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

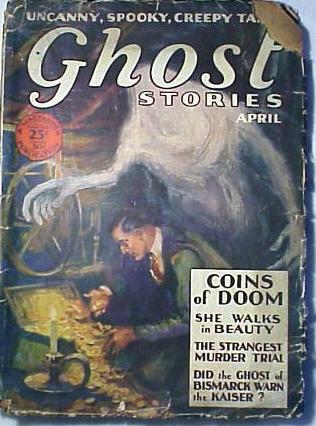

Published in Ghost Stories, Vol. 6, No. 4 (April 1929).

Many fights are won and lost by the living, but this is a tale of one which was won by a man dead over a hundred years. John Taverel, manager of ring champions, sitting in the old East Side A.C. one cold wintry day, told me this story of the ghost that won the fight and the man who worshipped the ghost. Let John Taverel tell the tale in his own words, as he told it to me:

You remember Ace Jessel, the great negro boxer whom I managed. An ebony giant he was, four inches over six feet in height, his fighting weight two hundred and thirty pounds. He moved with the smooth ease of a gigantic leopard and his pliant steel muscles rippled under his shiny skin. A clever boxer for so large a man, he carried the smashing jolt of a trip hammer in each huge black fist.

Yet for all that, the road over which I, as his manager, steered him, was far from smooth and at times I despaired, for Ace seemed to lack a fighting heart. Courage he had plenty, courage to stand up to a vicious beating and to keep on going after his face had been pounded and battered to a bloody mass, as he proved in that terrible battle with Maul Finnegan, which became almost mythical in boxing annals. Courage he had, but not the aggressiveness which drives the perfect fighter ever to the attack, nor the killer instinct which sends him plunging after the reeling, bloody and beaten foe. And a boxer who lacks these qualities is likely to fail when put to the supreme test.

Ace was content to box mostly, outpointing his opponents and piling up just enough lead to keep from losing. And the public was never fond of these tactics. Therefore they jeered and booed him every so often, but though their taunts angered me, they only broadened Ace’s good-natured grin. And his fights still drew great crowds because on the rare occasions when he was stung out of his defensive role, or when he was matched with a clever man whom he had to knock out in order to win, the fans saw a real battle that thrilled their blood. And even so, time and again he stepped away from a sagging foe, giving the beaten man time to recover and return to the attack, instead of finishing him—while the crowd raved and I tore my hair.

Now Ace Jessel, indifferent drifter, happy-go-lucky wastrel though he seemed, had one deep and abiding emotion, and that was a fanatical worship for one Tom Molyneaux, first champion of America and sturdy fighting man of color—according to some authorities, the greatest black ringman that ever lived.

Tom Molyneaux died in Ireland a hundred years ago but the memory of his valiant deeds in America and Europe was Ace Jessel’s direct incentive to action. Reading an account of Tom’s life and battles was what started Ace on the fistic trail which led from the wharves where he toiled as a young boy, to—but listen to the story.

Ace’s most highly prized possession was a painted portrait of the old battler. He had discovered this—a rare find indeed, since even woodcuts of Molyneaux are rare—among the collections of a London sportsman, and had prevailed on the owner to sell it. Paying for it had taken every cent that Ace made in four fights but he counted it cheap at the price. He removed the original frame and replaced it with a frame of solid silver, a slim elegant work of art which, considering that the portrait was full length and life size, was rather more than extravagant. But no honor was too expensive for “Misto Tom” and Ace simply tripled the number of his bouts to meet the cost.

So finally my brains and Ace’s mallet fists had cleared us a road to the top of the game. Ace loomed up as a heavyweight menace and the champion’s manager was ready to sign with us when an interruption came.

A form hove into view on the fistic horizon which dwarfed and overshadowed all other contenders, including my man. This was Mankiller Gomez. He was all which his name implies. Gomez was his ring name, given him by the Spaniard who discovered him and brought him to America. His real name was Balanga Guma and he was a full-blooded Senegalese from the West Coast of Africa.

Once in a century ring fans see a man like Gomez in action. Once in a hundred years there rises a fighter like the Senegalese—a born killer who crashes through the general ruck of fighters as a buffalo crashes through a thicket of dead wood. He was a savage, a tiger. What he lacked in actual skill, he made up by ferocity of attack, by ruggedness of body and smashing power of arm. From the time he landed in New York, with a long list of European victories behind him, it was inevitable that he should batter down all opposition, and at last the white champion looked to see the black savage looming above the broken forms of his victims. The champion saw the writing on the wall, but the public was clamoring for a match and whatever else his faults, the title holder was a fighting champion.

Ace Jessel, who alone of all the foremost challengers had not met Gomez, was shoved into discard, and as early summer dawned on New York, a title was lost and won, and Mankiller Gomez, son of the black jungle, rose up king of all fighting men.

The sporting world and the public at large hated and feared the new champion. Boxing fans like savagery in the ring, but Gomez did not confine his ferocity to the ring. His soul was abysmal. He was ape-like, primordial—the very spirit of that morass of barbarism from which mankind has so tortuously climbed, and toward which men look with so much suspicion.

There went forth a search for a White Hope, but the result was always the same. Challenger after challenger went down before the terrible onslaught of the Mankiller and at last only one man remained who had not crossed gloves with Gomez—Ace Jessel.

I hesitated in throwing my man in with a battler like Gomez, for my fondness for the great good-natured negro was more than the friendship of manager for fighter. Ace was something more than a meal-ticket to me for I knew the real nobility underlying Ace’s black skin, and I hated to see him battered into a senseless ruin by a man I knew in my heart to be more than Jessel’s match. I wanted to wait awhile, to let Gomez wear himself out with his terrific battles and the dissipations that were sure to follow the savage’s success. These super-sluggers never last long, any more than a jungle native can withstand the temptations of civilization.

But the slump that follows a really great title holder’s gaining the belt was on, and matches were scarce. The public was clamoring for a title fight, sports writers were raising Cain and accusing Ace of cowardice, promoters were offering alluring purses, and at last I signed for a fifteen round go between Mankiller Gomez and Ace Jessel.

At the training quarters I turned to Ace.

“Ace, do you think you can whip him?”

“Misto John,” Ace answered, meeting my eye with a straight gaze, “Ah’ll do mah best, but Ah’s mighty afeard Ah cain’t do it. Dat man ain’t human.” I knew this was bad; a man is more than half whipped when he goes into the ring in that frame of mind.

Later I came into Ace’s room for something and halted in the doorway in amazement. I had heard the battler talking in a low voice as I came up, but had supposed one of the handlers or sparring partners was in the room with him. Now I saw that he was alone. He was standing before his idol—the portrait of Tom Molyneaux.

“Misto Tom,” he was saying humbly, “Ah ain’t nevah met no man yet what could even knock me off mah feet, but Ah reckon dat nigguh can. Ah’s gwine to need help mighty bad, Misto Tom.”

I felt almost as if I had interrupted a religious rite. It was uncanny—had it not been for Ace’s evident deep sincerity, I would have felt it to be unholy. But to Ace, Tom Molyneaux was something more than a saint. I stood in the doorway in silence, watching the strange tableau. The artist who painted the picture so long ago had wrought with remarkable skill. The short black figure seemed to stand out boldly from the faded canvas. A breath of bygone days, it seemed, clad in the long tights of that other day, the powerful legs braced far apart, the knotted arms held stiffly and high, just as Molyneaux had appeared when he fought Tom Cribb of England so long ago.

Ace Jessel stood before the painted figure, head sunk upon his mighty chest as if listening to some dim whisper inside his own soul. And as I watched, a curious and fantastic thought came into my brain—the memory of an age-old superstition. You know it has been said by delvers into the occult that the carving of statues or the painting of pictures has power to draw back from the void of Eternity souls long flown, and to recreate them in shadowy semblance. I wondered if Ace had ever heard of this superstition and thought by doing obeisance to Molyneaux’s portrait to conjure the dead man’s spirit out of the realms of the dead for advice and aid. I shrugged my shoulders at this ridiculous idea and turned away. As I did, I glanced again at the picture before which Ace still stood like a great image of black basalt, and was aware of a peculiar illusion; the canvas seemed to ripple slightly, like the surface of a lake across which a faint breeze is blowing.

However I forgot all this as the day of the fight drew near.

The great crowd cheered Ace to the echo as he climbed in the ring; cheered again, not so heartily, as Gomez appeared. They afforded a strange contrast, those two negroes, alike in color but how different in all other aspects!

Ace was tall, clean-limbed and rangy, long and smooth of muscle, clear of eye and broad of forehead.

Gomez seemed stocky by comparison, though he stood a good six feet two. Where Jessel’s sinews were long and smooth like great cables, his were knotty and bulging. His calves, thighs, arms and shoulders stood out in great bunches of muscles. His small bullet head was set squarely between gigantic shoulders, and his forehead was so low that his kinky wool seemed to lower over his small bestial and bloodshot eyes. On his chest was a thick grizzle of matted black hair.

He grinned cavernously, thumped his breast and flexed his mighty arms with the insolent assurance of the savage. Ace, in his corner, grinned at the crowd, but an ashy tint was on his dusky face and his knees trembled.

The usual remarks were made, instructions given by the referee, weights announced—230 for Ace, 248 for Gomez—then over the great stadium the lights went off save for those over the ring where two black giants faced each other like men alone on the ridge of the world.

At the gong Gomez whirled in his corner and came out with a breath-taking roar of pure ferocity. Ace, frightened though he must have been, rushed to meet him with the courage of a cave man charging a gorilla, and they met headlong in the center of the ring.

The first blow was the Mankiller’s, a left swing that glanced Ace’s ribs. Jessel came back with a long left to the face and a straight right to the body that stung. Gomez bulled in, swinging both hands and Ace, after one futile attempt to mix it with him, gave back. The champion drove him across the ring, sending in a savage left to the body as Ace clinched. As they broke Gomez shot a terrible right to the chin and Ace reeled into the ropes. A great “Ahhh!” went up from the crowd as the champion plunged after him like a famished wolf, but Ace managed to dive between the lashing arms and clinch, shaking his head to clear it. Gomez sent in a left, largely smothered by Ace’s clutching arms, and the referee warned the Senegalese.

At the break Ace stepped back, jabbing swift and cleverly with his left, and the round ended with the champion, bellowing like a buffalo, trying to get past that rapier-like arm.

Between rounds I cautioned Ace to keep away from infighting as much as possible, where Gomez’s superior strength would count heavily, and to use his footwork to avoid punishment as much as he could.

The second round started much like the first, Gomez rushing and Ace using all his skill to stave him off and avoid those terrible smashes. It’s hard to get a shifty boxer like Ace in a corner, when he is fresh and unweakened and at long range had the advantage of his superior science over Gomez, whose one idea was to get in close and batter down his foes by sheer strength and ferocity. Still, in spite of Ace’s speed and skill, just before the gong sounded Gomez got the range and sank a vicious left to the wrist in Ace’s midriff and the tall negro weaved slightly as he walked to his corner. I could see the beginning of the end. The vitality and power of Gomez seemed endless; there was no wearing him down and it would not take many of his blows, landed, to rob Ace of his speed of foot and accuracy of eye. Then, forced to stand and trade punches, he was done.

Gomez, seeing he had stung his man, came plunging out for the third round with murder in his eye. He ducked a straight left, took a hard right uppercut square in the face and hooked both hands to the body, then straightened with a terrific right to the chin, which Ace robbed of most of its force by swaying with the blow. And while the champion was still off balance, Ace measured him coolly and shot in a fierce right hook flush on the chin. Gomez’s head flew back as if hinged to his shoulders and he was stopped in his tracks, but even as the crowd rose, hands clenching, lips parted, in hopes he would go down, the champion shook his bullet head and came in roaring. The round ended with both men locked in a clinch in the center of the ring.

At the beginning of the fourth round Gomez attacked and drove Ace about the ring before a shower of blows which he could not seem to wholly avoid. Stung and desperate, Ace made a stand in a neutral corner and sent Gomez back on his heels with a left and right to the body, but took a savage left to the face in return. Then suddenly the champion crashed through with a deadly left to the solar plexus and as Ace staggered, shot a killing right to the chin. Ace fell back into the ropes, instinctively raising his hands and sinking his chin on his chest. Gomez’s short fierce smashes were partly blocked by his shielding gloves and suddenly, pinned on the ropes as he was, and still dazed from the Mankiller’s attack, Ace went into terrific action and, slugging toe to toe with the champion, beat him off and drove him back across the ring!

The crowd went insane but, crouching behind Ace’s corner, I saw the writing on the wall. Ace was fighting as he had never fought before, but no man on earth could stand the pace the champion was setting.

Battling along the ropes, Ace sent a savage left to the body and a right and left to the face but was repaid by a right-hand smash to the ribs that made him wince in spite of himself, and just at the gong Gomez landed another of those deadly left-handers to the body.

Ace’s handlers worked over him swiftly, for I saw that the tall black was weakening. A few more rounds of this would spell the end.

“Ace, can’t you keep away from those body smashes?”

“Misto John, suh, Ah’ll try,” he answered.

The gong! Ace came in with a rush, his magnificent body vibrating with dynamic energy. Gomez met him, his iron muscles bunching into a compact fighting unit. Crash—crash—and again, crash! A clinch. And as they broke, Gomez drew back his great right arm and launched a terrible blow to Ace’s mouth. The tall negro reeled—he went down! Then, without stopping for the count which I was screaming for him to take, he gathered his long steely legs under him and was up with a bound, blood gushing down his black chest. Gomez leaped in and Ace, with the fury of desperation, met him with a terrific right, square to the jaw. And Gomez crashed to the canvas on his shoulder blades! The crowd rose screaming! In the space of ten seconds both men had been floored for the first time in the life of each!

“One! Two! Three! Four!” the referee’s arm rose and fell.

Gomez was up, unhurt, wild with fury. Roaring like a wild beast, he plunged in, brushed aside Ace’s hammering arms and crashed his right hand with the full weight of his mighty shoulder behind it, full into Ace’s midriff. Jessel went an ashy color—he swayed like a tall tree, and Gomez beat him to his knees with rights and lefts which sounded like the blows of caulking mallets.

“One! Two! Three! Four!—”

Ace was writhing on the canvas, striving to get his legs beneath him. The roar of the fans was a torrent of sound, an ocean of noise which drowned out all thought.

“Five! Six! Seven!—”

Ace was up! Gomez came charging across the stained canvas, gibbering his pagan fury. His blows beat upon the staggering challenger like a hail of sledges. A left—a right—another left which Ace had not strength to duck.

“One! Two! Three! Four! Five! Six! Seven! Eight!—”

Again Ace was up, weaving, staring blankly, helpless. A swinging left hurled him back into the ropes and rebounding from them he went to his knees—the gong!

As his handlers and I sprang into the ring Ace groped blindly for his corner and dropped limply upon the stool.

“Ace, he’s too much for you.”

A grin bent Jessel’s bloody lips and an indomitable spirit looked out of his bloodshot eyes.

“Misto John, please suh, don’t t’row in de sponge. Must Ah take it, Ah takes it standin’. Dat boy cain’t last at dis pace all night, suh.”

No, but neither could Ace Jessel, in spite of his remarkable vitality and his marvelous recuperative powers which sent him back up for the next round, with a show of renewed strength and freshness, at least.

The sixth and seventh were comparatively tame. Perhaps Gomez really was fatigued from the terrific pace he had been setting. At any rate, Ace managed to make it more or less of a sparring match at long range and the crowd was treated to an exhibition showing how long a man, out on his feet, can stand off and keep away from a slugger bent solely on his destruction. Even I marveled at the brand of boxing which Ace was showing, even though I knew that Gomez was fighting cautiously, for him. He had sampled the power of Ace’s right hand in that frenzied fifth round and perhaps he was wary of a trick. For the first time in his life he had sprawled on the canvas. He knew he was winning, and I think he was content to rest a couple of rounds, take his time for a space and gather his energies for a final onslaught.

This began as the gong sounded for the eighth round. Gomez launched his usual sledge hammer attack, drove Ace about the ring and floored him in a neutral corner. His style of fighting was such that when he was determined on a foe’s destruction, skill, speed and science could not avert but only postpone the eventual outcome. Ace took the count of nine and rose, back-pedalling. But Gomez was after him; the champion missed twice with his left and then sank a right under the heart that turned Ace ashy. A left to the jaw made his knees buckle and he clinched desperately. On the break-away Ace sent a straight left to the face and right hook to the chin, but the blows lacked their old force and Gomez shook them off and sank his left wrist deep in Ace’s midsection. Ace again clinched but the champion shoved him away and drove him across the ring with savage hooks to the body. At the gong they were slugging along the ropes.

Ace reeled to the wrong corner, and when his handlers led him to his own, he sank down on the stool, his legs trembling and his great dusky chest heaving from his superhuman exertions. I glanced across at the champion who sat glowering at his foe. He too was showing signs of the fray, but he was much fresher than Ace. The referee walked over, looked at Jessel hesitantly and then spoke to me.

Through the mists which veiled his bruised brain, Ace realized the import of his words and struggled to rise, a kind of fear flaming in his eyes.

“Misto John, don’ let him stop it, suh! Don’ let him do it! Ah ain’t hu’t nuthin’ like dat ’ud hu’t me!”

The referee shrugged his shoulders and walked back to the center of the ring, and I turned to one of the trainers and bade him bring me the flat bundle I had brought with me into the stadium.

There was little use giving advice to Ace. He was too battered to understand—in his numbed brain there was room only for one thought—to fight and fight, and keep on fighting—the old primal instinct that is stronger than all things save death.

At the sound of the gong he reeled out to meet his doom with an indomitable courage that brought the crowd to its feet yelling. He struck, a wild aimless left, and the champion plunged in hitting with both hands until Ace went down. At “nine” he was up and back-pedalled instinctively until Gomez reached him with a long straight right and sent him down again. Again he took “nine” before he reeled up and now the crowd was silent. Not one voice was raised in an urge for the kill. This was butchery, primitive slaughter, and the courage of Ace Jessel took their breath as it gripped my heart.

Ace fell blindly into a clinch, and another and another, till the Mankiller, furious, shook him off and sank his right to the body. Ace’s ribs gave way like rotten wood, with a dry crack heard distinctly all over the stadium—a strangled cry went up from the crowd and Jessel gasped thickly and fell to his knees.

“—Seven! Eight!—” and the great black form was writhing on the canvas.

“—Nine!” and the miracle had happened and Ace was on his feet, swaying, jaw sagging, arms hanging limply.

Gomez glared at him, not in pity, but as if unable to understand how his foe could have risen again, then came plunging in to finish him. Ace was in dire straits. Blood blinded him and his feet slipped in great smears of it on the canvas—his blood. Both eyes were nearly closed, and when he breathed gustily through his smashed nose, a red haze surrounded him. Deep cuts gashed cheek and cheek bones and his left side was a mass of battered red flesh. He was going on fighting instinct alone now, and never again would any man doubt that Ace Jessel had a fighting heart.

Yet a fighting heart alone is not enough when the body that holds it is broken and battered and mists of unconsciousness veil the brain. Ace sank down before Gomez’s panting onslaught and this time the crowd knew that it was final.

When a man has taken the beating that Ace had taken, something more than body and heart must come into the game to carry him through. Something to inspire and stimulate the dazed brain, to fire it to heights of super-human achievement. I had planned to furnish this inspiration, if the worst came to the worst, in the only way which I knew would touch Ace.

Before leaving the training quarters, I had, unknown to Ace, removed the picture of Tom Molyneaux from its frame, and brought it to the stadium with me, carefully wrapped. I now took this, and as Ace’s eyes, instinctively and without his own volition, sought his corner, I held the portrait up, just outside the glare of the ring lights, so while illumined by them, it appeared illusive and dim. It may be thought that I acted wrongly and selfishly, to thus seek to bring to his feet for more punishment a man almost dead from the beating, but the outsider cannot fathom the souls of the children of the fight game, to whom winning is greater than life, and losing, worse than death.

All eyes were glued on the prostrate form in the center of the ring, on the wind-blown champion sagging against the ropes, on the arm of the referee, which rose and fell with the regularity of doom. I doubt if four men in the audience saw my action, but Ace Jessel saw. I caught the gleam that came into his bloodshot and dazed eyes. I saw him shake his head violently. I saw him begin sluggishly to gather his long legs under him. It seemed a long time; the drone of the referee rose as it neared its climax—then, by all the gods, Ace Jessel was up! The crowd went insane and screaming.

I saw his eyes blaze with a strange wild light. And as I live today, the picture in my hands shook suddenly and violently!

A cold wind passed like death across me and I heard the man next to me shiver involuntarily as he drew his coat closer about him. But it was no cold wind that gripped my soul as I looked, wide-eyed and staring, into the ring where the greatest drama the boxing world has ever known was being enacted. There was Ace Jessel, bloody, terrible, throbbing and pulsing with new dynamic life, fired by a superhuman power—there was Mankiller Gomez, speechless with amazement at his foe’s new burst of fury—there was the immobile-faced referee—and to my horror I saw that there were four men in that ring!

And the fourth—a short, massive black man, barrel-chested and mighty-limbed, clad in the long tights of another day. And as I looked I saw that this man was not as other men for beyond him I saw the ropes of the ring and dimly, the ring lights, as if I were looking through a dark mist—as if I were looking through him.

His mighty arm was about Ace Jessel’s waist as my fighter crashed upon the weary and disheartened Gomez; his bare hard fists fell with Ace’s on the head and body of the desperate Mankiller. Whether Gomez saw or realized he saw this Stranger, I do not know. Dazed by the unnaturalness of Ace’s sudden comeback, by the uncanny strength of Ace who should have been fainting on the canvas, Gomez staggered, weakening; bewildered and mazed he was unable to decide upon a stand to make, and before he could rally was beaten down, crashed and battered down and out by long straight smashes sent in with the speed and power of a pile driver. And the last blow, a straight right that would have felled an ox, and did fell Mankiller Gomez, was driven not alone by the power of Ace’s mighty shoulder, but by the aid of a shadowy black hand on Jessel’s wrist. As I live today, that Fourth Man guided Ace’s hand to Gomez’s chin and backed the blow with the power of his own tremendous shoulders.

A moment the strange tableau burned itself into my brain. The astounded referee counting over the prostrate champion, and Ace Jessel, standing, head lowered and arms dangling, supported by a short, mighty figure in long ring tights. Then this figure faded before my very gaze and, as the portrait of Tom Molyneaux fell from my nerveless fingers, I felt it shake as if it shuddered.

As I climbed into the ring with the roar of the insane fans thundering in my brain, I wondered dazedly as I wonder today—was I given to see that sight alone of all that throng because I held the picture in my hands?

The crowd saw only a miracle, a man beaten nearly to death coming back with unexplainable strength and vitality to conquer his conqueror. They did not see the Fourth Man. Nor did Mankiller Gomez.

Ace Jessel? A negro never talks on some subjects and I have never asked him any questions on that matter. But as he collapsed in his corner, I bent over him and heard him murmur as he lost consciousness:

“Misto Tom—he done it, suh—his han’ was on mah wrist—when—Ah—dropped—Gomez.”

That old superstition is justified as far as I am concerned. Hereafter I will not doubt that deep devotion coupled with the possession of a life-like portrait, can conjure back from the unknown voids of the astral world, the soul or spirit or ghost which inhabited the living body of which the portrait is a likeness. A door perhaps, a portrait is, through which astral beings pass back and forth between this world and the next—whatever that world may be.

But when I said no man save Ace Jessel and I saw the Fourth Man, I am not altogether correct. After the bout the referee, a steely-nerved, cold-eyed son of the old-time school, said to me:

“Did you notice in that last round that a cold wind seemed to blow across the ring? Now tell me straight, am I going crazy or did I see a dark shadow hovering about Ace Jessel when he dropped Gomez?”

“You did,” I answered. “And unless we are all insane, the ghost of Tom Molyneaux was in that ring tonight.”