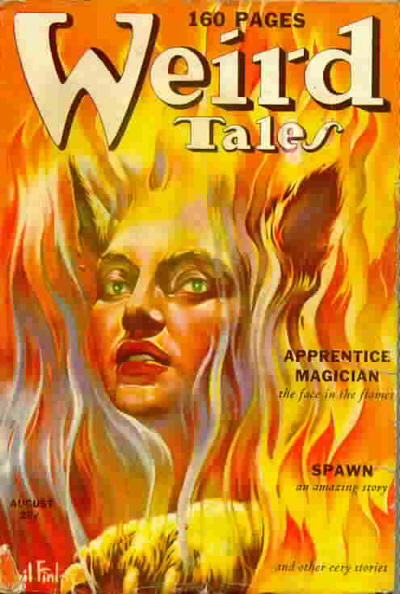

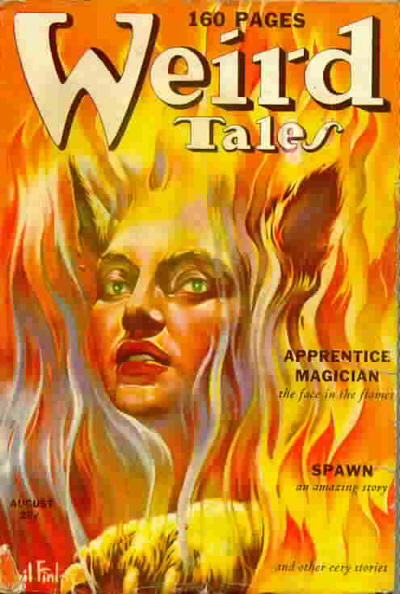

Interestingly, the August 1939 cover illustration was re-used for Vol. 46, No. 4 (September 1954), the issue that reprinted Howard’s “The Dark Man.”

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

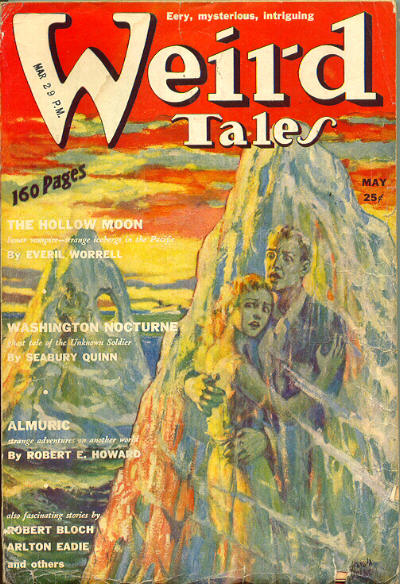

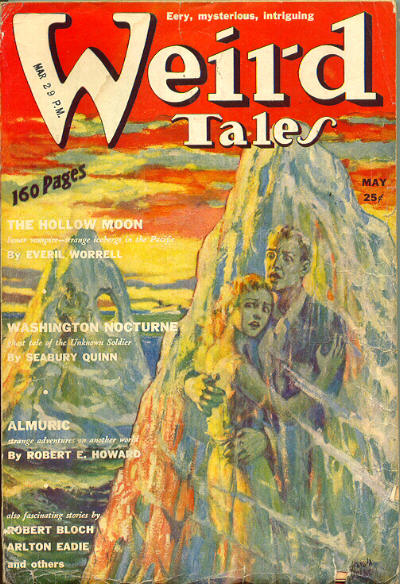

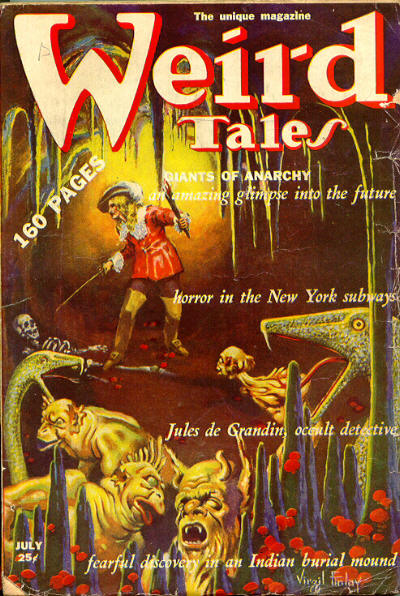

Published in Weird Tales, Vol. 33, No. 5 (May 1939), and Vol. 34, Nos. 1-2 (June and August 1939; there was no July issue).

In early 1934, Howard wrote a first draft and the first half of a second one, but then for unknown reasons abandoned the novel.

It lingered for several years, until it was eventually published in Weird Tales after Howard’s death, completed by another writer.

Interestingly, the August 1939 cover illustration was re-used for Vol. 46, No. 4 (September 1954), the issue that reprinted Howard’s “The Dark Man.”

| Foreword Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 |

Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 |

Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 |

It was not my original intention ever to divulge the whereabouts of Esau Cairn, or the mystery surrounding him. My change of mind was brought about by Cairn himself, who retained a perhaps natural and human desire to give his strange story to the world which had disowned him and whose members can now never reach him. What he wishes to tell is his affair. One phase of my part of the transaction I refuse to divulge; I will not make public the means by which I transported Esau Cairn from his native Earth to a planet in a solar system undreamed of by even the wildest astronomical theorists. Nor will I divulge by what means I later achieved communication with him, and heard his story from his own lips, whispering ghostily across the cosmos.

Let me say that it was not premeditated. I stumbled upon the Great Secret quite by accident in the midst of a scientific experiment, and never thought of putting it to any practical use, until that night when Esau Cairn groped his way into my darkened observatory, a hunted man, with the blood of a human being on his hands. It was chance led him there, the blind instinct of the hunted thing to find a den wherein to turn at bay.

Let me state definitely and flatly, that, whatever the appearances against him, Esau Cairn is not, and was never, a criminal. In that specific case he was merely the pawn of a corrupt political machine which turned on him when he realized his position and refused to comply further with its demands. In general, the acts of his life which might suggest a violent and unruly nature simply sprang from his peculiar mental make-up.

Science is at last beginning to perceive that there is sound truth in the popular phrase, “born out of his time.” Certain natures are attuned to certain phases or epochs of history, and these natures, when cast by chance into an age alien to their reactions and emotions, find difficulty in adapting themselves to their surroundings. It is but another example of nature’s inscrutable laws, which sometimes are thrown out of stride by some cosmic friction or rift, and result in havoc to the individual and the mass.

Many men are born outside their century; Esau Cairn was born outside his epoch. Neither a moron nor a low-class primitive, possessing a mind well above the average, he was, nevertheless, distinctly out of place in the modern age. I never knew a man of intelligence so little fitted for adjustment in a machine-made civilization. (Let it be noted that I speak of him in the past tense; Esau Cairn lives, as far as the cosmos is concerned; as far as the Earth is concerned, he is dead, for he will never again set foot upon it.)

He was of a restless mold, impatient of restraint and resentful of authority. Not by any means a bully, he at the same time refused to countenance what he considered to be the slightest infringement on his rights. He was primitive in his passions, with a gusty temper and a courage inferior to none on this planet. His life was a series of repressions. Even in athletic contests he was forced to hold himself in, lest he injure his opponents. Esau Cairn was, in short, a freak—a man whose physical body and mental bent leaned back to the primordial.

Born in the Southwest, of old frontier stock, he came of a race whose characteristics were inclined toward violence, and whose traditions were of war and feud and battle against man and nature. The mountain country in which he spent his boyhood carried out the tradition. Contest—physical contest—was the breath of life to him. Without it he was unstable and uncertain. Because of his peculiar physical make-up, full enjoyment in a legitimate way, in the ring or on the football field was denied him. His career as a football player was marked by crippling injuries received by men playing against him, and he was branded as an unnecessarily brutal man, who fought to maim his opponents rather than win games. This was unfair. The injuries were simply resultant from the use of his great strength, always so far superior to that of the men opposed to him. Cairn was not a great sluggish lethargic giant as so many powerful men are; he was vibrant with fierce life, ablaze with dynamic energy. Carried away by the lust of combat, he forgot to control his powers, and the result was broken limbs or fractured skulls for his opponents.

It was for this reason that he withdrew from college life, unsatisfied and embittered, and entered the professional ring. Again his fate dogged him. In his training-quarters, before he had had a single match, he almost fatally injured a sparring partner. Instantly the papers pounced upon the incident, and played it up beyond its natural proportions. As a result Cairn’s license was revoked.

Bewildered, unsatisfied, he wandered over the world, a restless Hercules, seeking outlet for the immense vitality that surged tumultuously within him, searching vainly for some form of life wild and strenuous enough to satisfy his cravings, born in the dim red days of the world’s youth.

Of the final burst of blind passion that banished him for ever from the life wherein he roamed, a stranger, I need say little. It was a nine-days’ wonder, and the papers exploited it with screaming headlines. It was an old story—a rotten city government, a crooked political boss, a man chosen, unwittingly on his part, to be used as a tool and serve as a puppet.

Cairn, restless, weary of the monotony of a life for which he was unsuited, was an ideal tool—for a while. But Cairn was neither a criminal nor a fool. He understood their game quicker than they expected, and took a stand surprisingly firm to them, who did not know the real man.

Yet, even so, the result would not have been so violent if the man who had used and ruined Cairn had any real intelligence. Used to grinding men under his feet and seeing them cringe and beg for mercy, Boss Blaine could not understand that he was dealing with a man to whom his power and wealth meant nothing. Yet so schooled was Cairn to iron self-control that it required first a gross insult, then an actual blow on the part of Blaine, to rouse him. Then for the first time in his life, his wild nature blazed into full being. All his thwarted and repressed life surged up behind the clenched fist that broke Blaine’s skull like an eggshell and stretched him lifeless on the floor, behind the desk from which he had for years ruled a whole district.

Cairn was no fool. With the red haze of fury fading from his glare, he realized that he could not hope to escape the vengeance of the machine that controlled the city. It was not because of fear that he fled Blaine’s house. It was simply because of his primitive instinct to find a more convenient place to turn at bay and fight out his death fight.

So it was that chance led him to my observatory.

He would have left, instantly, not wishing to embroil me in his trouble, but I persuaded him to remain and tell me his story. I had long expected some catastrophe of the sort. That he had repressed himself as long as he did, shows something of his iron character. His nature was as wild and untamed as that of a maned lion.

He had no plan—he simply intended to fortify himself somewhere and fight it out with the police until he was riddled with lead.

I at first agreed with him, seeing no better alternative. I was not so naive as to believe he had any chance in the courts with the evidence that would be presented against him. Then a sudden thought occurred to me, so fantastic and alien, and yet so logical, that I instantly propounded it to my companion. I told him of the Great Secret, and gave him proof of its possibilities.

In short, I urged him to take the chance of a flight through space, rather than meet the certain death that awaited him.

And he agreed. There was no place in the universe which would support human life. But I had looked beyond the knowledge of men, in universes beyond universes. And I chose the only planet I knew on which a human being could exist—the wild, primitive, and strange planet I named Almuric.

Cairn understood the risks and uncertainties as well as I. But he was utterly fearless—and the thing was done. Esau Cairn left the planet of his birth, for a world swimming afar in space, alien, aloof, strange.

The transition was so swift and brief, that it seemed less than a tick of time lay between the moment I placed myself in Professor Hildebrand’s strange machine, and the instant when I found myself standing upright in the clear sunlight that flooded a broad plain. I could not doubt that I had indeed been transported to another world. The landscape was not so grotesque and fantastic as I might have supposed, but it was indisputably alien to anything existing on the Earth.

But before I gave much heed to my surroundings, I examined my own person to learn if I had survived that awful flight without injury. Apparently I had. My various parts functioned with their accustomed vigor. But I was naked. Hildebrand had told me that inorganic substance could not survive the transmutation. Only vibrant, living matter could pass unchanged through the unthinkable gulfs which lie between the planets. I was grateful that I had not fallen into a land of ice and snow. The plain seemed filled with a lazy summerlike heat. The warmth of the sun was pleasant on my bare limbs.

On every side stretched away a vast level plain, thickly grown with short green grass. In the distance this grass attained a greater height, and through it I caught the glint of water. Here and there throughout the plain this phenomenon was repeated, and I traced the meandering course of several rivers, apparently of no great width. Black dots moved through the grass near the rivers, but their nature I could not determine. However, it was quite evident that my lot had not been cast on an uninhabited planet, though I could not guess the nature of the inhabitants. My imagination peopled the distances with nightmare shapes.

It is an awesome sensation to be suddenly hurled from one’s native world into a new strange alien sphere. To say that I was not appalled at the prospect, that I did not shrink and shudder in spite of the peaceful quiet of my environs, would be hypocrisy. I, who had never known fear, was transformed into a mass of quivering, cowering nerves, starting at my own shadow. It was that man’s utter helplessness was borne in upon me, and my mighty frame and massive thews seemed frail and brittle as the body of a child. How could I pit them against an unknown world? In that instant I would gladly have returned to Earth and the gallows that awaited me, rather than face the nameless terrors with which imagination peopled my new-found world. But I was soon to learn that those thews I now despised were capable of carrying me through greater perils than I dreamed.

A slight sound behind me brought me around to stare amazedly at the first inhabitant of Almuric I was to encounter. And the sight, awesome and menacing as it was, yet drove the ice from my veins and brought back some of my dwindling courage. The tangible and material can never be as grisly as the unknown, however perilous.

At my first startled glance I thought it was a gorilla which stood before me. Even with the thought I realized that it was a man, but such a man as neither I nor any other Earthman had ever looked upon.

He was not much taller than I, but broader and heavier, with a great spread of shoulders, and thick limbs knotted with muscles. He wore a loincloth of some silklike material girdled with a broad belt which supported a long knife in a leather sheath. High-strapped sandals were on his feet. These details I took in at a glance, my attention being instantly fixed in fascination on his face.

Such a countenance it is difficult to imagine or describe. The head was set squarely between the massive shoulders, the neck so squat as to be scarcely apparent. The jaw was square and powerful, and as the wide thin lips lifted in a snarl, I glimpsed brutal tusklike teeth. A short bristly beard masked the jaw, set off by fierce, up-curving mustaches. The nose was almost rudimentary, with wide flaring nostrils. The eyes were small, bloodshot, and an icy gray in color. From the thick black brows the forehead, low and receding, sloped back into a tangle of coarse, bushy hair. The ears were small and very close-set.

The mane and beard were very blue-black, and the creature’s limbs and body were almost covered with hair of the same hue. He was not, indeed, as hairy as an ape, but he was hairier than any human being I had ever seen.

I instantly realized that the being, hostile or not, was a formidable figure. He fairly emanated strength—hard, raw, brutal power. There was not an ounce of surplus flesh on him. His frame was massive, with heavy bones. His hairy skin rippled with muscles that looked iron-hard. Yet it was not altogether his body that spoke of dangerous power. His look, his carriage, his whole manner reflected a terrible physical might backed by a cruel and implacable mind. As I met the blaze of his bloodshot eyes, I felt a wave of corresponding anger. The stranger’s attitude was arrogant and provocative beyond description. I felt my muscles tense and harden instinctively.

But for an instant my resentment was submerged by the amazement with which I heard him speak in perfect English!

“Thak! What manner of man are you?”

His voice was harsh, grating and insulting. There was nothing subdued or restrained about him. Here were the naked primitive instincts and manners, unmodified. Again I felt the old red fury rising in me, but I fought it down.

“I am Esau Cairn,” I answered shortly, and halted, at a loss how to explain my presence on his planet.

His arrogant eyes roved contemptuously over my hairless limbs and smooth face, and when he spoke, it was with unbearable scorn.

“By Thak, are you a man or a woman?”

My answer was a smash of my clenched fist that sent him rolling on the sward.

The act was instinctive. Again my primitive wrath had betrayed me. But I had no time for self-reproach. With a scream of bestial rage my enemy sprang up and rushed at me, roaring and frothing. I met him breast to breast, as reckless in my wrath as he, and in an instant was fighting for my life.

I, who had always had to restrain and hold down my strength lest I injure my fellow men, for the first time in my life found myself in the clutches of a man stronger than myself. This I realized in the first instant of impact, and it was only by the most desperate efforts that I fought clear of his crushing embrace.

The fight was short and deadly. The only thing that saved me was the fact that my antagonist knew nothing of boxing. He could—and did—strike powerful blows with his clenched fists, but they were clumsy, ill-timed and erratic. Thrice I mauled my way out of grapples that would have ended with the snapping of my spine. He had no knack of avoiding blows; no man on Earth could have survived the terrible battering I gave him. Yet he incessantly surged in on me, his mighty hands spread to drag me down. His nails were almost like talons, and I was quickly bleeding from a score of places where they had torn the skin.

Why he did not draw his dagger I could not understand, unless it was because he considered himself capable of crushing me with his bare hands—which proved to be the case. At last, half blinded by my smashes, blood gushing from his split ears and splintered teeth, he did reach for his weapon, and the move won the fight for me.

Breaking out of a half-clinch, he straightened out of his defensive crouch and drew his dagger. And as he did so, I hooked my left into his belly with all the might of my heavy shoulders and powerfully driving legs behind it. The breath went out of him in an explosive gasp, and my fist sank to the wrist in his belly. He swayed, his mouth flying open, and I smashed my right to his sagging jaw. The punch started at my hip, and carried every ounce of my weight and strength. He went down like a slaughtered ox and lay without twitching, blood spreading out over his beard. That last smash had torn his lip open from the corner of his mouth to the rim of his chin, and must surely have fractured his jawbone as well.

Panting from the fury of the bout, my muscles aching from his crushing grasp, I worked my raw, skinned knuckles, and stared down at my victim, wondering if I had sealed my doom. Surely, I could expect nothing now but hostility from the people of Almuric. Well, I thought, as well be hanged for a sheep as a goat. Stooping, I despoiled my adversary of his single garment, belt and weapon, and transferred them to my own frame. This done, I felt some slight renewal of confidence. At least I was partly clothed and armed.

I examined the dagger with much interest. A more murderous weapon I have never seen. The blade was perhaps nineteen inches in length, double-edged, and sharp as a razor. It was broad at the haft, tapering to a diamond point. The guard and pommel were of silver, the hilt covered with a substance somewhat like shagreen. The blade was indisputably steel, but of a quality I had never before encountered. The whole was a triumph of the weapon-maker’s art, and seemed to indicate a high order of culture.

From my admiration of my newly acquired weapon, I turned again to my victim, who was beginning to show signs of returning consciousness. Instinct caused me to sweep the grasslands, and in the distance, to the south, I saw a group of figures moving toward me. They were surely men, and armed men. I caught the flash of the sunlight on steel. Perhaps they were of the tribe of my adversary. If they found me standing over their senseless comrade, wearing the spoils of conquest, their attitude toward me was not hard to visualize.

I cast my eyes about for some avenue of escape or refuge, and saw that the plain, some distance away, ran up into low green-clad foothills. Beyond these in turn, I saw larger hills, marching up and up in serried ranges. Another glance showed the distant figures to have vanished among the tall grass along one of the river courses, which they must cross before they reached the spot where I stood.

Waiting for no more, I turned and ran swiftly toward the hills. I did not lessen my pace until I reached the foot of the first foothills, where I ventured to look back, my breath coming in gasps, and my heart pounding suffocatingly from my exertions. I could see my antagonist, a small shape in the vastness of the plain. Further on, the group I was seeking to avoid had come into the open and were hastening toward him.

I hurried up the low slope, drenched with sweat and trembling with fatigue. At the crest I looked back once more, to see the figures clustered about my vanquished opponent. Then I went down the opposite slope quickly, and saw them no more.

An hour’s journeying brought me into as rugged a country as I have ever seen. On all sides rose steep slopes, littered with loose boulders, which threatened to roll down upon the wayfarer. Bare stone cliffs, reddish in color, were much in evidence. There was little vegetation, except for low stunted trees, of which the spread of their branches was equal to the height of the trunk, and several varieties of thorny bushes, upon some of which grew nuts of peculiar shape and color. I broke open several of these, finding the kernel to be rich and meaty in appearance, but I dared not eat it, although I was feeling the bite of hunger.

My thirst bothered me more than my hunger, and this at least I was able to satisfy, although the satisfying nearly cost me my life. I clambered down a precipitous steep and entered a narrow valley, enclosed by lofty cliffs, at the foot of which the nut-bearing bushes grew in great abundance. In the middle of the valley lay a broad pool, apparently fed by a spring. In the center of the pool the water bubbled continuously, and a small stream led off down the valley.

I approached the pool eagerly, and lying on my belly at its lush-grown marge, plunged my muzzle into the crystal-clear water. It, too, might be lethal for an Earthman, for all I knew, but I was so maddened with thirst that I risked it. It had an unusual tang, a quality I have always found present in Almuric water, but it was deliciously cold and satisfying. So pleasant it was to my parched lips that after I had satisfied my thirst, I lay there enjoying the sensation of tranquility. That was a mistake. Eat quickly, drink quickly, sleep lightly, and linger not over anything—those are the first rules of the wild, and his life is not long who fails to observe them.

The warmth of the sun, the bubbling of the water, the sensuous feeling of relaxation and satiation after fatigue and thirst—these wrought on me like an opiate to lull me into semislumber. It must have been some subconscious instinct that warned me, when a faint swishing reached my ears that was not part of the rippling of the spring. Even before my mind translated the sound as the passing of a heavy body through the tall grass, I whirled on my side, snatching at my poniard.

Simultaneously my ears were stunned with a deafening roar, there was a rushing through the air, and a giant form crashed down where I had lain an instant before, so close to me that its outspread talons raked my thigh. I had no time to tell the nature of my attacker—I had only a dazed impression that it was huge, supple, and catlike. I rolled frantically aside as it spat and struck at me sidewise; then it was on me, and even as I felt its claws tear agonizingly into my flesh, the ice-cold water engulfed us both. A catlike yowl rose half strangled, as if the yowler had swallowed a large amount of water. There was a great splashing and thrashing about me; then as I rose to the surface, I saw a long, bedraggled shape disappearing around the bushes near the cliffs. What it was I could not say, but it looked more like a leopard than anything else, though it was bigger than any leopard I had ever seen.

Scanning the shore carefully, I saw no other enemy, and crawled out of the pool, shivering from my icy plunge. My poniard was still in its scabbard. I had had no time to draw it, which was just as well. If I had not rolled into the pool, just when I did, dragging my attacker with me, it would have been my finish. Evidently the beast had a true catlike distaste for water.

I found that I had a deep gash in my thigh and four lesser abrasions on my shoulder, where a great talon-armed paw had closed. The gash in my leg was pouring blood, and I thrust the limb deep into the icy pool, swearing at the excruciating sting of the cold water on the raw flesh. My leg was nearly numb when the bleeding ceased.

I now found myself in a quandary. I was hungry, night was coming on, there was no telling when the leopard-beast might return, or another predatory animal attack me; more than that, I was wounded. Civilized man is soft and easily disabled. I had a wound such as would be considered, among civilized people, ample reason for weeks of an invalid’s existence. Strong and rugged as I was, according to Earth standards, I despaired when I surveyed the wound, and wondered how I was to treat it. The matter was quickly taken out of my hands.

I had started across the valley toward the cliffs, hoping I might find a cave there, for the nip of the air warned me that the night would not be as warm as the day, when a hellish clamor up near the mouth of the valley caused me to wheel and glare in that direction. Over the ridge came what I thought to be a pack of hyenas, except for their noise, which was more infernal than an Earthly hyena, even, could produce. I had no illusions as to their purpose. It was I they were after.

Necessity recognizes few limitations. An instant before I had been limping painfully and slowly. Now I set out on a mad race for the cliff as if I were fresh and unwounded. With every step a spasm of agony shot along my thigh, and the wound, bleeding afresh, spurted red, but I gritted my teeth and increased my efforts.

My pursuers gave tongue and raced after me with such appalling speed that I had almost given up hope of reaching the trees beneath the cliffs before they pulled me down. They were snapping at my heels when I lurched into the low stunted growths, and swarmed up the spreading branches with a gasp of relief. But to my horror the hyenas climbed after me! A desperate downward glance showed me that they were not true hyenas; they differed from the breed I had known just as everything on Almuric differed subtly from its nearest counterpart on Earth. These beasts had curving catlike claws, and their bodily structure was catlike enough to allow them to climb as well as a lynx.

Despairingly, I was about to turn at bay, when I saw a ledge on the cliff above my head. There the cliff was deeply weathered, and the branches pressed against it. A desperate scramble up the perilous slant, and I had dragged my scratched and bruised body up on the ledge and lay glaring down at my pursuers, who loaded the topmost branches and howled up at me like lost souls. Evidently their climbing ability did not include cliffs, because after one attempt, in which one sprang up toward the ledge, clawed frantically for an instant on the sloping stone wall, and then fell off with an awful shriek, they made no effort to reach me.

Neither did they abandon their post. Stars came out, strange unfamiliar constellations, that blazed whitely in the dark velvet skies, and a broad golden moon rose above the cliffs, and flooded the hills with weird light; but still my sentinels sat on the branches below me and howled up at me their hatred and belly-hunger.

The air was icy, and frost formed on the bare stone where I lay. My limbs became stiff and numb. I had knotted my girdle about my leg for a tourniquet; the run had apparently ruptured some small veins laid bare by the wound, because the blood flowed from it in an alarming manner.

I never spent a more miserable night. I lay on the frosty stone ledge, shaking with cold. Below me the eyes of my hunters burned up at me. Throughout the shadowy hills sounded the roaring and bellowing of unknown monsters. Howls, screams and yapping cut the night. And there I lay, naked, wounded, freezing, hungry, terrified, just as one of my remote ancestors might have lain in the Paleolithic Age of my own planet.

I can understand why our heathen ancestors worshipped the sun. When at last the cold moon sank and the sun of Almuric pushed its golden rim above the distant cliffs, I could have wept for sheer joy. Below me the hyenas snarled and stretched themselves, bayed up at me briefly, and loped away in search of easier prey. Slowly the warmth of the sun stole through my cramped, numbed limbs, and I rose stiffly up to greet the day, just as that forgotten forbear of mine might have stood up in the youthdawn of the Earth.

After a while I descended, and fell upon the nuts clustered in the bushes near by. I was faint from hunger, and decided that I had as soon die from poisoning as from starvation. I broke open the thick shells and munched the meaty kernels eagerly, and I cannot recall any Earthly meal, howsoever elaborate, that tasted half as good. No ill effects followed; the nuts were good and nutritious. I was beginning to overcome my surroundings, at least so far as food was concerned. I had surmounted one obstacle of life on Almuric.

It is needless for me to narrate the details of the following months. I dwelt among the hills in such suffering and peril as no man on Earth has experienced for thousands of years. I make bold to say that only a man of extraordinary strength and ruggedness could have survived as I did. I did more than survive. I came at last to thrive on the existence.

At first I dared not leave the valley, where I was sure of food and water. I built a sort of nest of branches and leaves on the ledge, and slept there at night. Slept? The word is misleading. I crouched there, trying to keep from freezing, grimly lasting out the night. In the daytime I snatched naps, learning to sleep anywhere, or at any time, and so lightly that the slightest unusual noise would awaken me. The rest of the time I explored my valley and the hills about, and picked and ate nuts. Nor were my humble explorations uneventful. Time and again I raced for the cliffs or the trees, winning sometimes by shuddering hairbreadths. The hills swarmed with beasts, and all seemed predatory.

It was that fact which held me to my valley, where I at least had a bit of safety. What drove me forth at last was the same reason that has always driven forth the human race, from the first apeman down to the last European colonist—the search for food. My supply of nuts became exhausted. The trees were stripped. This was not altogether on my account, although I developed a most ravenous hunger, what of my constant exertions; but others came to eat the nuts—huge shaggy bearlike creatures, and things that looked like fur-clad baboons. These animals ate nuts, but they were omnivorous, to judge by the attention they accorded me. The bears were comparatively easy to avoid; they were mountains of flesh and muscle, but they could not climb, and their eyes were none too good. It was the baboons I learned to fear and hate. They pursued me on sight, they could both run and climb, and they were not balked by the cliff.

One pursued me to my eyrie, and swarmed up onto the ledge with me. At least such was his intention, but man is always most dangerous when cornered. I was weary of being hunted. As the frothing apish monstrosity hauled himself up over my ledge, manlike, I drove my poniard down between his shoulders with such fury that I literally pinned him to the ledge; the keen point sinking a full inch into the solid stone beneath him.

The incident showed me both the temper of my steel, and the growing quality of my own muscles. I who had been among the strongest on my own planet, found myself a weakling on primordial Almuric. Yet the potentiality of mastery was in my brain and my thews, and I was beginning to find myself.

Since survival was dependent on toughening, I toughened. My skin, burnt brown by the sun and hardened by the elements, became more impervious to both heat and cold than I had deemed possible. Muscles I had not known I possessed became evident. Such strength and suppleness became mine as Earthmen have not known for ages.

A short time before I had been transported from my native planet, a noted physical culture expert had pronounced me the most perfectly developed man on Earth. As I hardened with my fierce life on Almuric, I realized that the expert honestly had not known what physical development was. Nor had I. Had it been possible to divide my being and set opposite each other the man that expert praised, and the man I had become, the former would have seemed ridiculously soft, sluggish and clumsy in comparison to the brown, sinewy giant opposed to him.

I no longer turned blue with the cold at night, nor did the rockiest way bruise my naked feet. I could swarm up an almost sheer cliff with the ease of a monkey, I could run for hours without exhaustion; in short dashes it would have taken a racehorse to outfoot me. My wounds, untended except for washing in cold water, healed of themselves, as Nature is prone to heal the hurts of such as live close to her.

All this I narrate in order that it may be seen what sort of a man was formed in the savage mold. Had it not been for the fierce forging that made me steel and rawhide, I could not have survived the grim bloody episodes through which I was to pass on that wild planet.

With new realization of power came confidence. I stood on my feet and stared at my bestial neighbors with defiance. I no longer fled from a frothing, champing baboon. With them, at least, I declared feud, growing to hate the abominable beasts as I might have hated human enemies. Besides, they ate the nuts I wished for myself.

They soon learned not to follow me to my eyrie, and the day came when I dared to meet one on even terms, I will never forget the sight of him frothing and roaring as he charged out of a clump of bushes, and the awful glare in his manlike eyes. My resolution wavered, but it was too late to retreat, and I met him squarely, skewering him through the heart as he closed in with his long clutching arms.

But there were other beasts which frequented the valley, and which I did not attempt to meet on any terms: the hyenas, the sabertooth leopards, longer and heavier than an Earthly tiger and more ferocious; giant mooselike creatures, carnivorous, with alligator-like tusks; the monstrous bears; gigantic boars, with bristly hair which looked impervious to a swordcut. There were other monsters, which appeared only at night, and the details of which I was not able to make out. These mysterious beasts moved mostly in silence, though some emitted high-pitched weird wails, or low Earth-shaking rumbles. As the unknown is most menacing, I had a feeling that these nighted monsters were even more terrible than the familiar horrors which harried my day-life.

I remember one occasion on which I awoke suddenly and found myself lying tensely on my ledge, my ears strained to a night suddenly and breathlessly silent. The moon had set and the valley was veiled in darkness. Not a chattering baboon, not a yelping hyena disturbed the sinister stillness. Something was moving through the valley; I heard the faint rhythmic swishing of the grass that marked the passing of some huge body, but in the darkness I made out only a dim gigantic shape, which somehow seemed infinitely longer than it was broad—out of natural proportion, somehow. It passed away up the valley, and with its going, it was as if the night audibly expelled a gusty sigh of relief. The nocturnal noises started up again, and I lay back to sleep once more with a vague feeling that some grisly horror had passed me in the night.

I have said that I strove with the baboons over the possession of the life-giving nuts. What of my own appetite and those of the beasts, there came a time when I was forced to leave my valley and seek far afield in search of nutriment. My explorations had become broader and broader, until I had exhausted the resources of the country close about. So I set forth at random through the hills in a southerly and easterly direction. Of my wanderings I will deal briefly. For many weeks I roamed through the hills, starving, feasting, threatened by savage beasts sleeping in trees or perilously on tall rocks when night fell. I fled, I fought, I slew, I suffered wounds. Oh, I can tell you my life was neither dull nor uneventful.

I was living the life of the most primitive savage; I had neither companionship, books, clothing, nor any of the things which go to make up civilization. According to the cultured viewpoint, I should have been most miserable. I was not. I revelled in my existence. My being grew and expanded. I tell you, the natural life of mankind is a grim battle for existence against the forces of nature, and any other form of life is artificial and without realistic meaning.

My life was not empty; it was crowded with adventures calling on every ounce of intelligence and physical power. When I swung down from my chosen eyrie at dawn, I knew that I would see the sun set only through my personal craft and strength and speed. I came to read the meaning of every waving grass tuft, each masking bush, each towering boulder. On every hand lurked Death in a thousand forms. My vigilance could not be relaxed, even in sleep. When I closed my eyes at night it was with no assurance that I would open them at dawn. I was fully alive. That phrase has more meaning than appears on the surface. The average civilized man is never fully alive; he is burdened with masses of atrophied tissue and useless matter. Life flickers feebly in him; his senses are dull and torpid. In developing his intellect he has sacrificed far more than he realizes.

I realized that I, too, had been partly dead on my native planet. But now I was alive in every sense of the word; I tingled and burned and stung with life to the finger tips and the ends of my toes. Every sinew, vein, and springy bone was vibrant with the dynamic flood of singing, pulsing, humming life. My time was too much occupied with food-getting and preserving my skin to allow the developing of the morbid and intricate complexes and inhibitions which torment the civilized individual. To those highly complex persons who would complain that the psychology of such a life is over-simple, I can but reply that in my life at that time, violent and continual action and the necessity of action crowded out most of the gropings and soul-searchings common to those whose safety and daily meals are assured them by the toil of others. My life was primitively simple; I dwelt altogether in the present. My life on Earth already seemed like a dream, dim and far away.

All my life I had held down my instincts, had chained and enthralled my over-abundant vitalities. Now I was free to hurl all my mental and physical powers into the untamed struggle for existence, and I knew such zest and freedom as I had never dreamed of.

In all my wanderings—and since leaving the valley I had covered an enormous distance—I had seen no sign of humanity, or anything remotely resembling humanity.

It was the day I glimpsed a vista of rolling grassland beyond the peaks, that I suddenly encountered a human being. The meeting was unexpected. As I strode along an upland plateau, thickly grown with bushes and littered with boulders, I came abruptly on a scene striking in its primordial significance.

Ahead of me the Earth sloped down to form a shallow bowl, the floor of which was thickly grown with tall grass, indicating the presence of a spring. In the midst of this bowl a figure similar to the one I had encountered on my arrival on Almuric was waging an unequal battle with a sabertooth leopard. I stared in amazement, for I had not supposed that any human could stand before the great cat and live.

Always the glittering wheel of a sword shimmered between the monster and its prey, and blood on the spotted hide showed that the blade had been fleshed more than once. But it could not last; at any instant I expected to see the swordsman go down beneath the giant body.

Even with the thought, I was running fleetly down the shallow slope. I owed nothing to the unknown man, but his valiant battle stirred newly plumbed depths in my soul. I did not shout but rushed in silently and murderously, my poniard gleaming in my hand. Even as I reached them, the great cat sprang, the sword went spinning from the wielder’s hand, and he went down beneath the hurtling bulk. And almost simultaneously I disembowled the sabertooth with one tremendous ripping stroke.

With a scream it lurched off its victim, slashing murderously as I leaped back, and then it began rolling and tumbling over the grass, roaring hideously and ripping up the Earth with its frantic talons, in a ghastly welter of blood and streaming entrails.

It was a sight to sicken the hardiest, and I was glad when the mangled beast stiffened convulsively and lay still.

I turned to the man, but with little hope of finding life in him. I had seen the terrible saberlike fangs of the giant carnivore tear into his throat as he went down.

He was lying in a wide pool of blood, his throat horribly mangled. I could see the pulsing of the great jugular vein which had been laid bare, though not severed. One of the huge taloned paws had raked down his side from arm-pit to hip, and his thigh had been laid open in a frightful manner; I could see the naked bone, and from the ruptured veins blood was gushing. Yet to my amazement the man was not only living, but conscious. Yet even as I looked, his eyes glazed and the light faded in them.

I tore a strip from his loincloth and made a tourniquet about his thigh which somewhat slackened the flow of blood; then I looked down at him helplessly. He was apparently dying, though I knew something of the stamina and vitality of the wild and its people. And such evidently this man was; he was as savage and hairy in appearance, though not quite so bulky, as the man I had fought during my first day on Almuric.

As I stood there helplessly, something whistled venomously past my ear and thudded into the slope behind me. I saw a long arrow quivering there, and a fierce shout reached my ears. Glaring about, I saw half a dozen hairy men running fleetly toward me, fitting shafts to their bows as they came.

With an instinctive snarl I bounded up the short slope, the whistle of the missiles about my head lending wings to my heels. I did not stop, once I had gained the cover of the bushes surrounding the bowl, but went straight on, wrathful and disgusted. Evidently men as well as beasts were hostile on Almuric, and I would do well to avoid them in the future.

Then I found my anger submerged in a fantastic problem. I had understood some of the shouts of the men as they rushed toward me. The words had been in English, just as the antagonist of my first encounter had spoken and understood that language. In vain I cudgeled my mind for a solution. I had found that while animate and inanimate objects on Almuric often closely copied things on Earth, yet there was almost a striking difference somewhere, in substance, quality, shape or mode of action. It was preposterous that certain conditions on the separate planets could run such a perfect parallel as to produce an identical language. Yet I could not doubt the evidence of my ears. With a curse I abandoned the problem as too fantastic to waste time on.

Perhaps it was this incident, perhaps the glimpse of the distant savannas, which filled me with a restlessness and distaste for the barren hill country where I had fared so hardily. The sight of men, strange and alien as they were, stirred in my breast a desire for human companionship, and this frustrated longing became in turn a sudden feeling of repulsion for my surroundings. I did not hope to meet friendly humans on the plains; but I determined to try my chances upon them, nevertheless, though what perils I might meet there I could not know. Before I left the hills some whim caused me to scrape from my face my heavy growth and trim my shaggy hair with my poniard, which had lost none of its razor edge. Why I did this I cannot say, unless it was the natural instinct of a man setting forth into new country to look his “best.”

The next morning I descended into the grassy plains, which swept eastward and southward as far as sight could reach. I continued eastward and covered many miles that day, without any unusual incident. I encountered several small winding rivers, along whose margins the grass stood taller than my head. Among this grass I heard the snorting and thrashing of heavy animals of some sort, and gave them a wide berth—for which caution I was later thankful.

The rivers were thronged in many cases with gaily colored birds of many shapes and hues, some silent, others continually giving forth strident cries as they wheeled above the waters or dipped down to snatch their prey from its depths.

Further out on the plain I came upon herds of grazing animals—small deerlike creatures, and a curious animal that looked like a pot-bellied pig with abnormally long hind legs, and that progressed in enormous bounds, after the fashion of a kangaroo. It was a most ludicrous sight, and I laughed until my belly ached. Later I reflected that it was the first time I had laughed—outside of a few short barks of savage satisfaction at the discomfiture of an enemy—since I had set foot on Almuric.

That night I slept in the tall grass not far from a water course, and might have been made the prey of any wandering meat-eater. But fortune was with me that night. All across the plains sounded the thunderous roaring of stalking monsters, but none came near my frail retreat. The night was warm and pleasant, strikingly in contrast with the nights in the chill grim hills.

The next day a momentous thing occurred. I had had no meat on Almuric, except when ravenous hunger had driven me to eat raw flesh. I had searched in vain for some stone that would strike a spark. The rocks were of a peculiar nature, unknown to Earth. But that morning on the plains, I found a bit of greenish-looking stone lying in the grass, and experiments showed that it had some of the qualities of flint. Patient effort, in which I clinked my poniard against the stone, rewarded me with a spark of fire in the dry grass, which I soon fanned to a blaze—and had some difficulty in extinguishing.

That night I surrounded myself with a ring of fire which I fed with dry grass and stalked plants which burned slowly and I felt comparatively safe, though huge forms moved about me in the darkness, and I caught the stealthy pad of great paws, and the glimmer of wicked eyes.

On my journey across the plains I subsisted on fruit I found growing on green stalks, which I saw the birds eating. It was pleasant to the taste, though lacking in the nutritive qualities of the nuts in the hills. I looked longingly at the scampering deerlike animals, now that I had the means of cooking their flesh, but saw no way of securing them.

And so for days I wandered aimlessly across those vast plains, until I came in sight of a massive walled city.

I sighted it just at nightfall, and eager though I was to investigate it further, I made my camp and waited for morning. I wondered if my fire would be seen by the inhabitants, and if they would send out a party to discover my nature and purpose.

With the fall of night I could no longer make it out, but the last waning light had shown it plainly, rising stark and somber against the eastern sky. At that distance no evidence of life was visible, but I had a dim impression of huge walls and massive towers, all of a greenish tint.

I lay within my circle of fire, while great sinuous bodies rustled through the grass and fierce eyes glared at me, and my imagination was at work as I strove to visualize the possible inhabitants of that mysterious city. Would they be of the same race as the hairy ferocious troglodytes I had encountered? I doubted it, for it hardly seemed possible that these primitive creatures would be capable of rearing such a structure. Perhaps there I would find a highly developed type of cultured man. Perhaps—here imaginings too dark and shadowy for description whispered at the back of my consciousness.

Then the moon rose behind the city, etching its massive outlines in the weird golden glow. It looked black and somber in the moonlight; there was something distinctly brutish and forbidding about its contours. As I sank into slumber I reflected that if apemen could build a city, it would surely resemble that colossus in the moon.

Dawn found me on my way across the plain. It may seem like the height of folly to have gone striding openly toward the city, which might be full of hostile beings, but I had learned to take desperate chances, and I was consumed with curiosity; weary at last of my lonely life.

The nearer I approached, the more rugged the details stood out. There was more of the fortress than the city about the walls, which, with the tower that loomed behind and above them, seemed to have been built of huge blocks of greenish stone, very roughly cut. There was no apparent attempt at smoothing, polishing, or otherwise adorning this stone. The whole appearance was rude and savage, suggesting a wild fierce people heaping up rocks as a defense against enemies.

As yet I had seen nothing of the inhabitants. The city might have been empty of human life. But a broad road leading to the massive gate was beaten bare of grass, as if by the constant impact of many feet. There were no fields or gardens about the city; the grass waved to the foot of the walls. All during that long march across the plain to the gates, I saw nothing resembling a human being. But as I came under the shadow of the great gate, which was flanked on either hand by a massive tower, I caught a glimpse of tousled black heads moving along the squat battlements. I halted and threw back my head to hail them. The sun had just topped the towers and its glare was full in my eyes. Even as I opened my lips, there was a cracking report like a rifle shot, a jet of white smoke spurted from a tower, and a terrific impact against my head dashed me into unconsciousness.

When I came to my senses it was not slowly, but quickly and clear-headedly, what with my immense recuperative powers. I was lying on a bare stone floor in a large chamber, the walls, ceiling and floor of which were composed of huge blocks of green stone. From a barred window high up in one wall sunlight poured to illuminate the room, which was without furnishing, except for a bench, crudely and massively built.

A heavy chain was looped about my waist and made fast with a strange, heavy lock. The other end of the chain was fastened to a thick ring set in the wall. Everything about the fantastic city seemed massive.

Lifting a hand to my head, I found it was bandaged with something that felt like silk. My head throbbed. Evidently whatever missile it was that had been fired at me from the wall, had only grazed my head, inflicting a scalp wound and knocking me senseless. I felt for my poniard, but naturally it was gone.

I cursed heartily. When I had found myself on Almuric I had been appalled by my prospects; but then at least I had been free. Now I was in the hands of God only knew what manner of beings. All I knew was that they were hostile. But my inordinate self-confidence would not down, and I felt no great fear. I did feel a rush of panic, common to all wild things, at being confined and shackled, but I fought down this feeling and it was succeeded by one of red unreasoning rage. Springing to my feet, which movement the chain was long enough to allow, I began jerking and tearing at my shackle.

It was while engaged in this fruitless exhibition of primitive resentment that a slight noise caused me to wheel, snarling, my muscles tensed for attack or defense. What I saw froze me in my tracks.

Just within the doorway stood a girl. Except in her garments she differed little from the type of girls I had known on Earth, except that her slim figure exhibited a suppleness superior to theirs. Her hair was intensely black, her skin white as alabaster. Her lissome limbs were barely concealed by a light, tuniclike garment, sleeveless, low-necked, revealing the greater part of her ivory breasts. This garment was girdled at her lithe waist, and came to within a few inches above her knees. Soft sandals encased her slender feet. She was standing in an attitude of awed fascination, her dark eyes wide, her crimson lips parted. As I wheeled and glared at her, she gave back with a quick gasp of surprise or fear, and fled lightly from the chamber.

I stared after her. If she were typical of the people of the city, then surely the effect produced by the brutish masonry was an illusion, for she seemed the product of some gentle and refined civilization, allowing for a certain barbaric suggestion about her costume.

While so musing, I heard the tramp of feet, harsh voices were lifted in argument, and the next instant a group of men strode into the chamber, halting as they saw me conscious and on my feet. Still thinking of the girl, I glared at them in surprise. They were of the same type as the others I had seen, huge, hairy, ferocious, with the same apelike forward-thrust heads and formidable faces. Some, I noticed, were darker than others, but all were dark and fierce, and the whole effect was one of somber and ferocious savagery. They were instinct with ferocity; it blazed in their icy-gray eyes, reflected in the snarling lift of their bristling lips, rumbled in their rough voices.

All were armed, and their hands seemed instinctively to seek their hilts as they stood glaring at me, their shaggy heads thrust forward in their apelike manner.

“Thak!” one exclaimed, or rather roared—all their voices were as gusty as a sea wind—“he’s conscious!”

“Do you suppose he can speak or understand human language?” rumbled another.

All this while I had stood glaring back at them, wondering anew at their speech. Now I realized that they were not speaking English.

The thing was so unnatural that it gave me a shock. They were not speaking any Earthly language, and I realized it, yet I understood them, except for various words which apparently had no counterpart on Earth. I made no attempt to understand this seemingly impossible phenomenon, but answered the last speaker.

“I can speak and understand.” I grunted. “Who are you? What city is this? Why did you attack me? Why am I in chains?”

They rumbled in amazement, with much tugging of mustaches, shaking of heads, and uncouth profanity.

“He talks, by Thak!” said one. “I tell you, he is from beyond the Girdle!”

“From beyond my hip!” broke in another rudely. “He is a freak, a damned, smooth-skinned degenerate misfit which should not have been born, or allowed to exist.”

“Ask him how he came by the Bonecrusher’s poniard,” requested yet another.

“Did you steal this from Logar?” he demanded.

“I stole nothing!” I snapped, feeling like a wild beast being prodded through the bars of a cage by unfeeling and critical spectators. My rages, like all the emotions on that wild planet, were without restraint.

“I took that poniard from the man who carried it, and I took it in a fair fight,” I added.

“Did you slay him?” they demanded unbelievingly.

“No,” I growled. “We fought with our bare hands, until he tried to knife me. Then I knocked him senseless.”

A roar greeted my words. I thought at first they were clamoring with rage; then I made out that they were arguing among themselves.

“I tell you he lies!” one bull’s bellow rose above the tumult. “We all know that Logar the Bonecrusher is not the man to be thrashed and stripped by a smooth-skinned hairless brown man like this. Ghor the Bear might be a match for Logar. No one else.”

“Well, there’s the poniard,” someone pointed out.

The clamor rose again, and in an instant the disputants were yelling and cursing, and brandishing their hairy fists in one another’s faces, hands fumbled at sword hilts, and challenges and defiances were exchanged freely.

I looked to see a general throat-cutting, but presently one who seemed in some authority drew his sword and began banging the hilt on the rude bench, at the same time drowning out the voices of the others with his bull-like bellowing.

“Shut up! Shut up! Let another man open his mouth and I’ll split his head!” As the clamor subsided and the disputants glared venomously at him, he continued in a voice as calm as if nothing had occurred. “It’s neither here nor there about the poniard. He might have caught Logar sleeping and brained him, or he might have stolen it, or found it. Are we Logar’s brothers, that we should seek after his welfare?”

A general snarl answered this. Evidently the man called Logar was not popular among them.

“The question is, what shall we do with this creature? We’ve got to hold a council and decide. He’s evidently uneatable.” He grinned as he said this, which was apparently meant as a bit of grim humor.

“His hide would make good leather.” suggested another in a tone that did not sound as though he was joking.

“Too soft,” protested another.

“He didn’t feel soft while we were carrying him in,” returned the first speaker. “He was hard as steel springs.”

“Tush,” deprecated the other. “I’ll show you how tender his flesh is. Watch me slice off a few strips.” He drew his dagger and approached me while the others watched with interest.

All this time my rage had been growing until the chamber seemed to swim in a red mist. Now, as I realized that the fellow really intended trying the edge of his steel on my skin I went berserk. Wheeling, I gripped the chain with both hands, wrapping it around my wrists for more leverage. Then, bracing my feet against the floor and walls I began to strain with all my strength. All over my body the great muscles coiled and knotted; sweat broke out on my skin, and then with a shattering crash the stone gave way, the iron ring was torn out bodily, and I was catapulted on my back onto the floor, at the feet of my captors who roared with amazement and fell on me en masse.

I answered their bellows with one strident yell of blood-thirsty gratification, and heaving up through the melee, began swinging my heavy fists like caulking mallets. Oh, that was a rough-house while it lasted! They made no attempt to knife me, striving to swamp me with numbers. We rolled from one side of the chamber to the other, a gasping, thrashing, cursing, hammering mass, while with the yells, howls, earnest profanity, and impact of heavy bodies, it was a perfect bedlam. Once I seemed to catch a fleeting glimpse of the door thronged with the heads of women similar to the one I had seen, but I could not be sure; my teeth were set in a hairy ear, my eyes were full of sweat and stars from a vicious punch on the nose, and what with a gang of heavy forms romping all over me my sight was none too good.

Yet, I gave a good account of myself. Ears split, noses crumpled and teeth splintered under the crushing impact of my iron-hard fists, and the yells of the wounded were music to my battered ears. But that damnable chain about my waist kept tripping me and coiling about my legs, and pretty soon the bandage was ripped from my head, my scalp wound opened anew and deluged me with blood. Blinded by this I floundered and stumbled, and gasping and panting they bore me down and bound my arms and legs.

The survivors then fell away from me and lay or sat in positions of pain and exhaustion while I, finding my voice, cursed them luridly. I derived ferocious satisfaction at the sight of all the bloody noses, black eyes, torn ears and smashed teeth which were in evidence, and barked in vicious laughter when one announced with many curses that his arm was broken. One of them was out cold, and had to be revived, which they did by dumping over him a vessel of cold water that was fetched by someone I could not see from where I lay. I had no idea that it was a woman who came in answer to a harsh roar of command.

“His wound is open again,” said one, pointing at me. “He’ll bleed to death.”

“I hope he does,” snarled another, lying doubled up on the floor. “He’s burst my belly. I’m dying. Get me some wine.”

“If you’re dying you don’t need wine,” brutally answered the one who seemed a chief, as he spat out bits of splintered teeth. “Tie up his wound, Akra.”

Akra limped over to me with no great enthusiasm and bent down.

“Hold your damnable head still,” he growled.

“Keep off!” I snarled. “I’ll have nothing from you. Touch me at your peril.”

He exasperatedly grabbed my face in his broad hand and shoved me violently down. That was a mistake. My jaws locked on his thumb, evoking an ear-splitting howl, and it was only with the aid of his comrades that he extricated the mangled member. Maddened by the pain, he howled wordlessly, then suddenly gave me a terrific kick in the temple, driving my wounded head with great violence back against the massive bench leg. Once again I lost consciousness.

When I came to myself again I was once more bandaged, shackled by the wrists and ankles, and made fast to a fresh ring, newly set in the stone, and apparently more firmly fixed than the other had been. It was night. Through the window I glimpsed the star-dotted sky. A torch which burned with a peculiar white flame was thrust into a niche in the wall, and a man sat on the bench, elbows on knees and chin on fists, regarding me intently. On the bench near him stood a huge gold vessel.

“I doubted if you’d come to after that last crack,” he said at last.

“It would take more than that to finish me,” I snarled. “You are a pack of cursed weaklings. But for my wound and that infernal chain, I’d have bested the whole mob of you.”

My insults seemed to interest rather than anger him. He absently fingered a large bump on his head on which blood was thickly clotted, and asked: “Who are you? Whence do you come?”

“None of your business,” I snapped.

He shrugged his shoulders, and lifting the vessel in one hand drew his dagger with the other.

“In Koth none goes hungry,” he said, “I’m going to place this food near your hand and you can eat. But I warn you, if you try to strike or bite me, I’ll stab you.”

I merely snarled truculently, and he bent and set down the bowl, hastily withdrawing. I found the food to be a kind of stew, satisfying both thirst and hunger. Having eaten I felt in somewhat better mood, and my guard renewed his questions, I answered: “My name is Esau Cairn. I am an American, from the planet Earth.”

He mulled over my statements for a space, then asked: “Are these places beyond the Girdle?”

“I don’t understand you,” I answered.

He shook his head. “Nor I you. But if you do not know of the Girdle, you cannot be from beyond it. Doubtless it is all fable, anyway. But whence did you come when we saw you approaching across the plain? Was that your fire we glimpsed from the towers last night?”

“I suppose so,” I replied. “For many months I have lived in the hills to the west. It was only a few weeks ago that I descended into the plains.”

He stared and stared at me.

“In the hills? Alone, and with only a poniard?”

“Well, what about it?” I demanded.

He shook his head as if in doubt or wonder. “A few hours ago I would have called you a liar. Now I am not sure.”

“What is the name of this city?” I asked.

“Koth, of the Kothan tribe. Our chief is Khossuth Skull-splitter. I am Thab the Swift. I am detailed to guard you while the warriors hold council.”

“What’s the nature of their council?” I inquired.

“They discuss what shall be done with you; and they have been arguing since sunset, and are no nearer a solution than before.”

“What is their disagreement?”

“Well,” he answered. “Some want to hang you, and some want to shoot you.”

“I don’t suppose it’s occurred to them that they might let me go,” I suggested with some bitterness.

He gave me a cold look. “Don’t be a fool,” he said reprovingly.

At that moment a light step sounded outside, and the girl I had seen before tiptoed into the chamber. Thab eyed her disapprovingly.

“What are you doing here, Altha?” he demanded.

“I came to look again at the stranger,” she answered in a soft musical voice. “I never saw a man like him. His skin is nearly as smooth as mine, and he has no hair on his countenance. How strange are his eyes! Whence does he come?”

“From the hills, he says,” grunted Thab.

Her eyes widened. “Why, none dwells in the hills, except wild beasts! Can it be that he is some sort of animal? They say he speaks and understands speech.”

“So he does,” growled Thab, fingering his bruises. “He also knocks out men’s brains with his naked fists, which are harder and heavier than maces. Get away from there.

“He’s a rampaging devil. If he gets his hands on you he won’t leave enough of you for the vultures to pick.”

“I won’t get near him,” she assured him. “But, Thab, he does not look so terrible. See, there is no anger in the gaze he fixes on me. What will be done with him?”

“The tribe will decide,” he answered. “Probably let him fight a sabertooth leopard bare-handed.”

She clasped her own hands with more human feeling than I had yet seen shown on Almuric.

“Oh, Thab, why? He has done no harm; he came alone and with empty hands. The warriors shot him down without warning—and now—”

He glanced at her in irritation. “If I told your father you were pleading for a captive—”

Evidently the threat carried weight. She visibly wilted.

“Don’t tell him,” she pleaded. Then she flared up again. “Whatever you say, it’s beastly! If my father whips me until the blood runs over my heels, I’ll still say so!”

And so saying, she ran quickly out of the chamber.

“Who is that girl?” I asked.

“Altha, the daughter of Zal the Thrower.”

“Who is he?”

“One of those you battled so viciously a short time ago.”

“You mean to tell me a girl like that is the daughter of a man like—” Words failed me.

“What’s wrong with her?” he demanded. “She differs none from the rest of our women.”

“You mean all the women look like her, and all the men look like you?”

“Certainly—allowing for their individual characteristics. Is it otherwise among your people? That is, if you are not a solitary freak.”

“Well, I’ll be—” I began in bewilderment, when another warrior appeared in the door, saying.

“I’m to relieve you, Thab. The warriors have decide to leave the matter to Khossuth when he returns on the morrow.”

Thab departed and the other seated himself on the bench. I made no attempt to talk to him. My head was swimming with the contradictory phenomena I had heard and observed, and I felt the need of sleep. I soon sank into dreamless slumber.

Doubtless my wits were still addled from the battering I had received. Otherwise I would have snapped awake when I felt something touch my hair. As it was, I woke only partly. From under drooping lids I glimpsed, as in a dream, a girlish face bent close to mine, dark eyes wide with frightened fascination, red lips parted. The fragrance of her foamy black hair was in my nostrils. She timidly touched my face, then drew back with a quick soft intake of breath, as if frightened by her action. The guard snored on the bench. The torch had burned to a stub that cast a weird dull glow over the chamber. Outside, the moon had set. This much I vaguely realized before I sank back into slumber again, to be haunted by a dim beautiful face that shimmered through my dreams.

I awoke again in the cold gray light of dawn, at a time when the condemned meet their executioners. A group of men stood over me, and one I knew was Khossuth the Skullsplitter.

He was taller than most, and leaner—almost gaunt in comparison to the others. This circumstance made his broad shoulders seem abnormally huge. His face and body were seamed with old scars. He was very dark, and apparently old; an impressive and terrible image of somber savagery.

He stood looking down at me, fingering the hilt of his great sword. His gaze was gloomy and detached.

“They say you claim to have beaten Logar of Thurga in open fight,” he said at last, and his voice was cavernous and ghostly in a manner I cannot describe.

I did not reply, but lay staring up at him, partly in fascination at his strange and menacing appearance, partly in the anger that seemed generally to be with me during those times.

“Why do you not answer?” he rumbled.

“Because I’m weary of being called a liar,” I snarled.

“Why did you come to Koth?”

“Because I was tired of living alone among wild beasts. I was a fool. I thought I would find human beings whose company was preferable to the leopards and baboons. I find I was wrong.”

He tugged his bristling mustaches.

“Men say you fight like a mad leopard. Thab says that you did not come to the gates as an enemy comes. I love brave men. But what can we do? If we free you, you will hate us because of what has passed, and your hate is not lightly to be loosed.”

“Why not take me into the tribe?” I remarked, at random.

He shook his head. “We are not Yagas, to keep slaves.”

“Nor am I a slave,” I grunted. “Let me live among you as an equal. I will hunt and fight with you. I am as good a man as any of your warriors.”

At this another pushed past Khossuth. This fellow was bigger than any I had yet seen in Koth—not taller, but broader, more massive. His hair was thicker on his limbs, and of a peculiar rusty cast instead of black.

“That you must prove!” he roared, with an oath. “Loose him, Khossuth! The warriors have been praising his power until my belly revolts! Loose him and let us have a grapple!”

“The man is wounded, Ghor,” answered Khossuth.

“Then let him be cared for until his wound is healed,” urged the warrior eagerly, spreading his arms in a curious grappling gesture.

“His fists are like hammers,” warned another.

“Thak’s devils!” roared Ghor, his eyes glaring, his hairy arms brandished. “Admit him into the tribe, Khossuth! Let him endure the test! If he survives—well, by Thak, he’ll be worthy even to be called a man of Koth!”

“I will go and think upon the matter,” answered Khossuth after a long deliberation.

That settled the matter for the time being. All trooped out after him. Thab was last, and at the door he turned and made a gesture which I took to be one of encouragement. These strange people seemed not entirely without feelings of pity and friendship.

The day passed uneventfully. Thab did not return. Other warriors brought me food and drink, and I allowed them to bandage my scalp. With more human treatment the wild-beast fury in me had been subordinated to my human reason. But that fury lurked close to the surface of my soul, ready to blaze into ferocious life at the slightest encroachment.

I did not see the girl Altha, though I heard light footsteps outside the chamber several times, whether hers or another’s I could not know.

About nightfall a group of warriors came into the room and announced that I was to be taken to the council, where Khossuth would listen to all arguments and decide my fate. I was surprised to learn that arguments would be presented on my behalf. They got my promise not to attack them, and loosed me from the chain that bound me to the wall, but they did not remove the shackles on my wrists and ankles.

I was escorted out of the chamber into a vast hall, lighted by white fire torches. There were no hangings or furnishings, nor any sort of ornamentation—just an almost oppressive sense of massive architecture.

We traversed several halls, all equally huge and windy, with rugged walls and lofty ceilings, and came at last into a vast circular space, roofed with a dome. Against the back wall a stone throne stood on a block-like dais, and on the throne sat old Khossuth in gloomy majesty, clad in a spotted leopardskin. Before him in a vast three-quarters circle sat the tribe, the men cross-legged on skins spread on the stone floor, and behind them the women and children seated on fur-covered benches.

It was a strange concourse. The contrast was startling between the hairy males and the slender, white-skinned, dainty women. The men were clad in loincloths and high-strapped sandals; some had thrown pantherskins over their massive shoulders. The women were dressed similar to the girl Altha, whom I saw sitting with the others. They wore soft sandals or none, and scanty tunics girdled about their waists. That was all. The difference of the sexes was carried out down to the smallest babies. The girl children were quiet, dainty and pretty. The young males looked even more like monkeys than did their elders.

I was told to take my seat on a block of stone in front and somewhat to the side of the dais. Sitting among the warriors I saw Ghor, squirming impatiently as he unconsciously flexed his thick biceps.

As soon as I had taken my seat, the proceedings went forward. Khossuth simply announced that he would hear the arguments, and pointed out a man to represent me, at which I was again surprised, but this apparently was a regular custom among these people. The man chosen was the lesser chief who had commanded the warriors I had battled in the cell, and they called him Gutchluk Tigerwrath. He eyed me venemously as he limped forward with no great enthusiasm, bearing the marks of our encounter.

He laid his sword and dagger on the dais, and the foremost warriors did likewise. Then he glared at the rest truculently, and Khossuth called for arguments to show why Esau Cairn—he made a marvelous jumble of the pronunciation—should not be taken into the tribe.

Apparently the reasons were legion. Half a dozen warriors sprang up and began shouting at the top of their voice, while Gutchluk dutifully strove to answer them. I felt already doomed. But the game was not played out, or even well begun. At first Gutchluk went at it only half-heartedly, but opposition heated him to his talk. His eyes blazed, his jaw jutted, and he began to roar and bellow with the best of them. From the arguments he presented, or rather thundered, one would have thought he and I were lifelong friends.

No particular person was designated to protest against me. Everybody who wished took a hand. And if Gutchluk won over anyone, that person joined his voice to Gutchluk’s. Already there were men on my side. Thab’s shout and Ghor’s bellow vied with my attorney’s roar, and soon others took up my defense.

That debate is impossible for an Earthman to conceive of, without having witnessed it. It was sheer bedlam, with from three voices to five hundred voices clamoring at once. How Khossuth sifted any sense out of it, I cannot even guess. But he brooded somberly above the tumult, like a grim god over the paltry aspirations of mankind.

There was wisdom in the discarding of weapons. Dispute frequently became biting, and criticisms of ancestors and personal habits entered into it. Hands clutched at empty belts and mustaches bristled belligerently. Occasionally Khossuth lifted his weird voice across the clamor and restored a semblance of order.

My attempts to follow the arguments were vain. My opponents went into matters seemingly utterly irrelevant, and were met by rebuttals just as illogical. Authorities of antiquity were dragged out, to be refuted by records equally musty.

To further complicate matters, disputants frequently snared themselves in their own arguments, or forgot which side they were on, and found themselves raging frenziedly on the other. There seemed no end to the debate, and no limit to the endurance of the debaters. At midnight they were still yelling as loudly, and shaking their fists in one another’s beards as violently as ever.

The women took no part in the arguments.

They began to glide away about midnight, with the children. Finally only one small figure was left among the benches. It was Altha, who was following—or trying to follow—the proceedings with a surprising interest.

I had long since given up the attempt. Gutchluk was holding the floor valiantly, his veins swelling and his hair and beard bristling with his exertions. Ghor was actually weeping with rage and begging Khossuth to let him break a few necks. Oh, that he had lived to see the men of Koth become adders and snakes, with the hearts of buzzards and the guts of toads! he bawled, brandishing his huge arms to high heaven.

It was all a senseless madhouse to me. Finally, in spite of the clamor, and the fact that my life was being weighed in the balance, I fell asleep on my block and snored peacefully while the men of Koth raged and pounded their hairy breasts and bellowed, and the strange planet of Almuric whirled on its way under the stars that neither knew nor cared for men, Earthly or otherwise.

It was dawn when Thab shook me awake and shouted in my ear: “We have won! You enter the tribe, if you’ll wrestle Ghor!”

“I’ll break his back!” I grunted, and went back to sleep again.

So began my life as a man among men on Almuric. I who had begun my new life as a naked savage, now took the next step on the ladder of evolution and became a barbarian. For the men of Koth were barbarians, for all their silks and steel and stone towers. Their counterpart is not on Earth today, nor has it ever been. But of that later. Let me tell first of my battle with Ghor the Bear.

My chains were removed and I was taken to a stone tower on the wall, there to dwell until my wounds had healed. I was still a prisoner. Food and drink were brought me regularly by the tribesmen, who also tended carefully to my wounds, which were unimportant, considering the hurts I had had from wild beasts, and had recovered from unaided. But they wished me to be in prime condition for the wrestling, which was to decide whether I should be admitted to the tribe of Koth, or—well, from what they said of Ghor, if I lost there would be no problem as to my disposition. The wolves and vultures would take care of that.

Their manner toward me was noncommittal, with the exception of Thab the Swift, who was frankly cordial to me. I saw neither Khossuth, Ghor nor Gutchluk during the time I was imprisoned in the tower, nor did I see the girl Altha.

I do not remember a more tedious and wearisome time. I was not nervous because of any fear of Ghor; I frankly doubted my ability to beat him, but I had risked my life so often and against such fearful odds, that personal fear had been stamped out of my soul. But for months I had lived like a mountain panther, and now to be caged up in a stone tower, where my movements were limited, bounded and restricted—it was intolerable, and if I had been forced to put up with it a day longer, I would have lost control of myself, and either fought my way to freedom or perished in the attempt. As it was, all the constrained energy in me was pent up almost to the snapping point, giving me a terrific store of nervous power which stood me in good stead in my battle.

There is no man on Earth equal in sheer strength to any man of Koth. They lived barbaric lives, filled with continuous peril and warfare against foes human and bestial. But after all, they lived the lives of men, and I had been living the life of a wild beast.